What Is Runoff Pollution?

Polluted runoff is one of the most harmful sources of pollution to the Bay and its waters. And much of it starts right in the urban and suburban neighborhoods where we live.

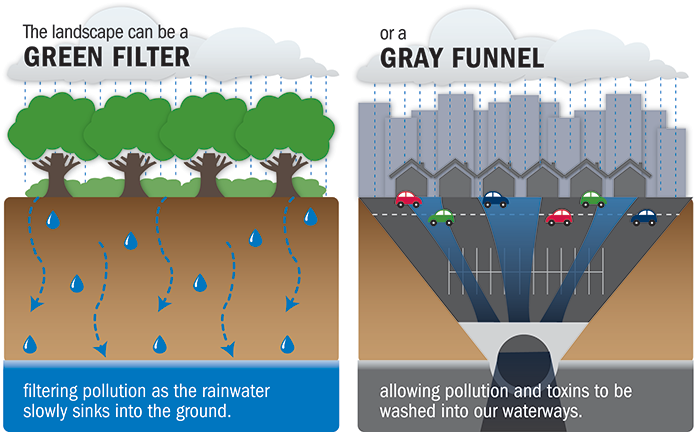

As rainwater and snowmelt run off our streets, parking lots, lawns, and other surfaces, they pick up pet waste, pesticides, fertilizer, oil, and other contaminants. If the draining water doesn’t evaporate or soak into the ground where it can be filtered, it flushes straight into local creeks, rivers, and the Chesapeake Bay, adversely affecting water quality and aquatic life.

Only 10 to 20 percent of rain that falls in forests, fields, and other natural areas runs off, with the rest absorbed by soil and plants, where it is filtered before reaching aquifers or local waterways. By contrast, close to 100 percent of the rain that falls on concrete and other hard surfaces produces runoff. One inch of rain falling on an acre of hardened surface produces 27,000 gallons of runoff.

Agricultural runoff from farmland, which carries nutrients from fertilizers and animal manure into rivers and streams, is also a problem.

Why Is Stormwater Runoff Pollution Increasing in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed?

Polluted runoff from stormwater is one of the primary sources of pollution still on the rise in our region. The amount of land covered by parking lots, roads, roofs, and driveways continues to grow. Meanwhile, forests, meadows, wetlands, and other natural filters are disappearing, and manmade filtration systems to control runoff have not compensated for the loss.

What Are Examples of Runoff Pollution?

Stormwater runoff collects an often-toxic mix of pollutants including:

- Trash

- Soil and sediment

- Fecal bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens

- Nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers and air pollution

- Oil and other petroleum products

- Pesticides and herbicides

- Road salt

- Toxic metals including copper, lead, and zinc

Effects of Runoff Pollution

The effects of runoff pollution are vast and long-lasting. It erodes streams, kills fish, pollutes both drinking water and swimming areas, floods homes, and causes many other problems. It is literally changing the landscape of our watershed by

- Reshaping waterways. Strong currents of runoff scour stream banks, destabilizing the natural contours of the streams and even altering their depths.

- Endangering aquatic life. Besides carrying pollutants that harm fish and other creatures, runoff also includes eroded dirt that blocks sunlight from reaching underwater grasses and smothers the aquatic homes of oysters and other life. As grasses die, fish and other creatures that rely on them are placed in jeopardy. The runoff also carries nutrients that spur algal blooms that cause low oxygen and kill fish and other species.

Not only wildlife is endangered by stormwater pollution; residents of the watershed region are deeply affected, too. Polluted runoff from urban and suburban areas is

- Affecting water quality. Runoff muddies drinking water sources and can carry bacteria, making the treatment and use of such water more expensive.

- Contaminating recreation areas. Virginia and Maryland caution people not to swim in waterways for 48 hours after a heavy rain, as polluted runoff carrying bacteria has resulted in serious illnesses.

- Increasing flood damage. In urban and suburban areas with lots of hard surfaces, leaving polluted water with no place to go, local streets and basements often flood, causing repeated and costly damage to homes and businesses. With climate change potentially increasing the amount of precipitation and intensity of storms, localized flooding can increase as once designated "100-year storms" occur with greater frequency.

How to Prevent Runoff Pollution

Chesapeake Bay Foundation

One promising solution to reducing runoff pollution in urban and suburban areas is to create “green infrastructure.” The idea is simple: Slow down and soak up the polluted runoff. Strategic greening efforts include

- planting rain gardens and other natural spaces in low-lying areas and in front of downspouts;

- attaching downspouts to rain barrels to collect rainwater, which can later be used for watering gardens;

- replacing old pavement with pervious pavement wherever possible;

- replacing grass with native plants;

- planting trees in yards, along streets, and along waterways; and

- planting gardens on rooftops.

These and other green solutions are cost-effective, beautify communities, and provide shade and wildlife habitat. We call this the “green filter” approach to managing runoff.

On agricultural lands, farmers can implement regenerative agriculture practices to reduce polluted runoff. These practices include

- planting forested buffers alongside streams;

- planting trees on land used for grazing;

- practicing rotational grazing, continuous no-till, and crop rotation;

- planting cover crops;

- managing fertilizer application; and

- using fences to keep livestock out of streams.

Agricultural cost-share programs provide farmers with critical federal and state funding to install these conservation practices. CBF's restoration staff work with farmers to install these practices.

CBF introduced local Bay jurisdictions to a new way of financing these green filters. It's called "impact investment." Projects help slow down and soak up runoff, and also create local sustainable jobs and more healthy, vibrant communities. Learn more about such a project in Hampton Roads, Virginia.

Did You Know

- The brake linings of cars and trucks are often made with copper and they shed a fine dust of this toxic metal onto streets, which can then end up in our waterways. The Maryland Department of the Environment sampled runoff from the state's major urban areas and found copper in 92 percent of the samples. Fifty-three percent of the time the levels would be acutely toxic to aquatic life. Another reason copper appears in waterways is because the metal is an ingredient in herbicides.

- Zinc from car tires, road salt, paint, and other products has also been found in runoff, as well as the toxic metals lead, chromium, and cadmium.

- Oil and other petroleum products in runoff are well known by scientists to be toxic to aquatic life, even in low concentrations.

- Researchers have detected pesticides including dieldrin and the now-banned chlordane in 97 percent of suburban and urban runoff samples nationally, and at levels high enough to harm aquatic life 83 percent of the time. For example, Lake Roland in Baltimore County is so polluted with chlordane, a termite-killing pesticide sprayed in nearby homes, that anglers are warned to limit their consumption of fish from the lake.

Additional information about stormwater management can be found at the following websites:

The Center for Watershed Protection

Low Impact Development Center

Low Impact Development Urban Design Tools

From Our Blog

-

Don't Leave Lakeside Planning up to Chance

January 3, 2024

Talbot County officials should closely monitor the development's growth and ensure sewage discharge and other plans are not harming Talbot's way of life.

-

Let's Pay Farmers for Outcomes That Restore Virginia Rivers, Streams, and the Chesapeake Bay

December 29, 2023

To create healthier rivers and streams for future generations Virginia legislators could launch a new pilot program that pays farmers based on how much cleaner they leave nearby waterways.

-

Stop the Influx of Industrial Sludge!

December 27, 2023

Maryland has become a dumping ground for the region's industrial sludge waste. But what is industrial sludge and why does it matter?

-

What Should the Future of Chesapeake Bay Watershed Restoration Look Like?

June 20, 2023

Leading researchers across the watershed released a seminal scientific report in May that sought to answer the question so many people are asking: Why is restoration taking so long?

-

New Conowingo Dam License Critical to Bay Restoration

February 16, 2023

The new Conowingo Dam license process can be transformative for the Bay, but only if Maryland officials can work through the challenges of dealing with the dam’s private operator, the utility Constellation Energy.

| Items 1 - 5 of 20 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Next |

Video

-

Case Study: Homeowner's Living Shoreline Stops Erosion

10 Nov 2020 00:03:55See how Virginia waterfront property owner Norman Colpitts uses a cost-effective living shoreline to protect his property while benefiting the environment. The living shoreline includes a small oyster reef to prevent erosion on his property. These oysters create wildlife habitat, filter and clean the water, and slow down waves before they erode the shore.

-

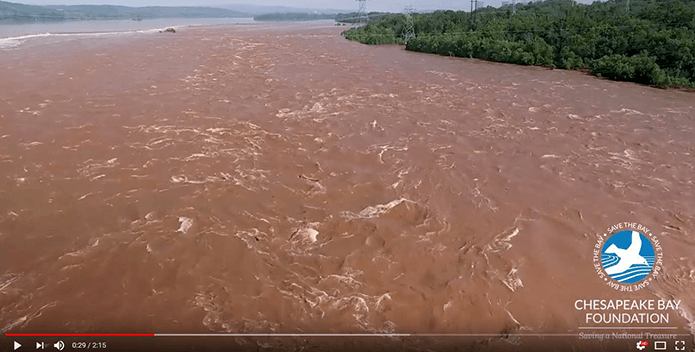

Raging Water on the Susquehanna

31 Jul 2018 Pavoncello Media Productions 00:02:16This video captures the devastating effects of heavy rains that pummeled Pennsylvania the week of July 23, 2018. These scenes were shot on July 26, the day before the river crested.

-

James River Runoff

09 May 2017 Facebook 00:00:11The James River in Richmond overflowed its banks after heavy rain washed huge amounts of dirt and pollutants into the current. Clear, clean water turned the color of chocolate milk. Even days after the storm the surge continues as runoff flows 200 miles downstream from the headwaters.

| Items 1 - 3 of 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Next |