While invasive blue catfish, Ictalurus furcatus, continue to eat the Chesapeake Bay alive, the voracious predators are being released and welcomed into parts of Pennsylvania, where they are native.

A restoration plan devised in 2022 by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) seeks to re-establish a sustainable, naturally reproducing population of native blue catfish in the Ohio River basin. The lower Allegheny and Monongahela rivers join the Ohio River at Pittsburgh to form the Three Rivers.

The PFBC believes the Three Rivers area has the right type of habitat and provides enough forage—including the catfish’s favorite gizzard shad—and other game fish to sustain a blue catfish population.

Blue catfish were already knocking at Pennsylvania’s door after the state of West Virginia stocked fingerlings in the Ohio River just west of the border with the Keystone State in 2013-15.

“They should still be here,” said Gary Smith, PFBC Fisheries Manager for the area. “We are re-establishing them where they belong.”

“The fact that blue catfish are not here isn’t their fault, it’s ours,” said PFBC Commissioner John Mahn Jr., who represents the Pittsburgh and Three Rivers region.

Native blues were extirpated from the Three Rivers around the turn of the 20th century as locks and dams curbed migration. Pollution from sewage, industrial plants, and mine drainage fouled waters. Fish kills were common. Cleanup over the last 50 years allowed water quality to improve and the re-emergence of catfish to be possible.

Blue Catfish Cause Problems in the Chesapeake

Meanwhile, in the Chesapeake Bay, blue catfish are wreaking havoc. Blue catfish were introduced in Virginia in the 1970s for recreational fishing. They expanded out of freshwater into the higher salinity waters of the Bay and exploded into other rivers and tributaries in Maryland and Virginia.

As opportunistic predators, blue catfish feed on valuable Bay species like menhaden, striped bass, eel, shad, river herring, and blue crabs. Studies found the invasive catfish make up 75 percent of the total biomass of fish in a small segment of Virginia’s James River.

Maryland Governor Wes Moore sought a declaration of a federal fisheries disaster from the U.S. Department of Commerce because of harm by blue catfish and snakeheads. It was denied in December. The declaration would have led to federal funding to address the threat to Maryland’s Bay fisheries, environment, and economy. Maryland’s Department of Agriculture has ramped up marketing efforts to promote wild-caught Chesapeake blue catfish to consumers.

Susquehanna at Risk of a Blue Catfish Invasion

As for the upper reaches of the Bay watershed in the Keystone State, there is strong consensus that blue catfish will become invasive and bring havoc to the Susquehanna River.

“They are coming, whether or not we stock blue cats into the Three Rivers,” Smith agreed.

Blue catfish are one of many nonnative, invasive species threatening to take over large sections of the Susquehanna and Bay, explained Harry Campbell, CBF Science Policy and Advocacy Director in Pennsylvania.

“It's cousin, the flathead catfish, is already in the Susquehanna,” Campbell said. “Blues will eat almost anything that fits in their mouths. And lots of it. Since they have long lifespans, if allowed to overrun the river they threaten many other species, including sport fisheries. Thankfully, they taste good!”

Their arrival seems inevitable.

“It’s like watching a car wreck in slow motion,” Mahn said. “At our best we are slowing this down. Hopefully it won’t be as bad as at the Bay. They are such good predators. They don’t grow that big being stupid.”

Sampling in Pennsylvania has already found environmental DNA (eDNA) from blue catfish, which is detected in water samples that contain DNA from sources like the fish’s scales or mucous.

“Scientists are increasingly using DNA to search for what’s lurking in the waters without ever seeing it,” Campbell said. “It’s like using a magnet in the hunt for needles in a haystack. Increasingly, eDNA analysis is being used to hunt for non-native and often invasive species. The hope is that if a sample comes back with a ‘hit,’ managers can act quickly to eradicate the offending species before it takes hold in the area and continues its spread elsewhere.”

PFBC Aquatic Invasive Species Coordinator Sean Hartzell is concerned about blue catfish getting into the Susquehanna from the Bay, moving up through the river’s system of hydroelectric dams, or by human transfer.

“Blue catfish are not entering the Susquehanna from the Ohio on their own,” Hartzell said. “We are blessed with hydroelectric dams in the Susquehanna, but it’s tricky because American shad and eels are native to the Susquehanna and need to migrate upriver.”

“We emphasized that this is a danger fish if it is put somewhere it doesn’t belong,” he added.

Allison Colden, CBF’s Maryland Executive Director cautioned that Pennsylvania should take heed of the many lessons learned from the expansion and boom of blue catfish in Maryland.

“A fish that was once thought to be limited to the upper freshwater reaches of rivers has proven to be much more tolerant and resilient than many expected, facilitating their spread throughout the Bay’s tributaries,” she said. “Perhaps most at risk from expansion of blue catfish into the Susquehanna are river herring and American shad. If, after surviving the many gauntlets of making their way hundreds of miles up the Bay, dodging fishing gear, through numerous fish ladders, these fish then face the formidable predator, blue catfish, it nearly extinguishes any hope of their long-term recovery.”

It is illegal for individuals to possess and to stock blue catfish in any water of the Commonwealth.

In Ohio Basin, Anglers See Blue Catfish Opportunity

In the Ohio River Basin, however, Pennsylvania anglers are looking forward to blue catfish’s return.

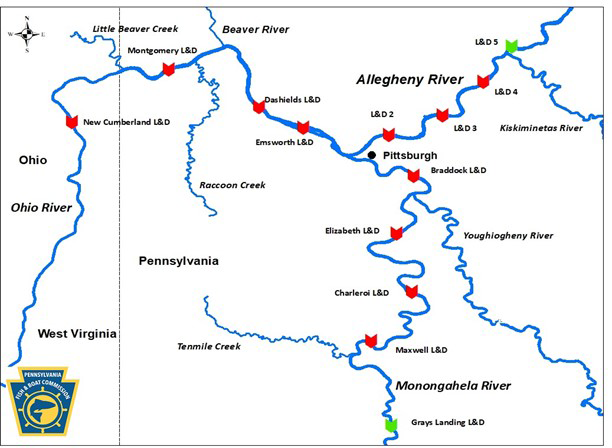

According to the restoration plan, five-years of annual stockings in the 40 river miles of the Ohio from Pittsburgh to the state line began in 2022; fingerlings the first year, yearlings after that. Targeted monitoring will begin in 2025. With noted progress, stocking into the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers would begin in 2027.

Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission map of Three Rivers "pools" for blue catfish. Red markers indicate locations where blue catfish are likely to congregate. "L&D" stands for Locks and Dam.

Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission

For all species of catfish in Pennsylvania, anglers may catch and keep up to 50 fish per day, of any size.

Blue catfish is a favorite among anglers for its fighting ability, year-round fishery, and potential to be the Commonwealth’s largest game fish.

The first blue catfish captured in the Pennsylvania portion of the Ohio River basin in over 100 years happened in 2019, and 11 more were taken the next year. The six caught in the Monongahela in 2021 and 2022 were likely stocked in West Virginia.

A recreational blue catfish fishery in the Three Rivers represents an economic boost for businesses catering to anglers, including sporting goods stores and bait shops, hospitality-related businesses such as hotels and restaurants, and service-related businesses such as gas stations and convenience stores, among others.

Jordan Miller runs guided bowfishing and rod and reel trips on the Three Rivers out of Sewickley, northwest of Pittsburgh, and sees the economic benefits of adding a “quality target” for customers.

“Blue catfish gives customers another species that they can take home and eat,” Miller says. “Blue cats are more visible in the water for bowfishing. Most of the fish we harvest legally with a bow (carp, catfish, suckers) are painted as a ‘trash fish.’ Suckers have a bad rep as nasty as bottom feeders.”

Miller is considering starting a blue catfish charter.

“Our river system is fairly deep, and we have so much structure, we don’t necessarily see the catfish like you would on the shallower Susquehanna,” he said.

For the fourth year in a row, a new record-breaking blue catfish was caught in West Virginia last December. The 50.5-inch fish from the Ohio River weighed almost 70 pounds.

“I don’t know that we will see catfish that big in the Three Rivers because of the shorter growing season,” Smith said. However, blues can move up in the Three Rivers if they negotiate locks and dams along the way.

In spite of their reputation as bottom-feeders, blue catfish can also be tasty table fare.

Jeff Geisel lives in southeastern Pennsylvania and represents Tilghman Island Seafood on the Bay’s Eastern Shore. The company processes 100,000 pounds of blue catfish each week.

“People who eat it think it is a different species, like Chilean Sea Bass,” Geisel says. “It is so tasteful because of what it is eating in the Bay.”

When it comes to the white meat of a blue catfish loin, Geisel likes his cut into portions and broiled with a bit of butter and lemon.