Baltimore is another step closer to cleaning up sewer overflows that threaten Chesapeake Bay water quality. At the end of December, the city activated its major headworks upgrade at the Back River Wastewater Treatment Plant—bringing online a $430 million fix to sewage overflows that frequently dumped wastewater into homes, streets, and surrounding waterways during and after rainstorms.

Baltimore's Department of Public Works (DPW) estimates the upgrades are expected to eliminate more than 80 percent of the volume of sewage that previously overflowed from the city's aged sewer system.

"It's one of many projects in our portfolio right now that shows the power of public infrastructure investments," said Matt Garbark, deputy director of DPW. "We think this is going to take the system to the next level and make us a national leader in terms of water quality."

The city undertook the Headworks Project as part of its efforts to meet the requirements of a federal consent decree put in place in 2002 to ensure the city complies with the Clean Water Act. The consent decree was modified in 2017, after the city failed to meet the initial terms.

CBF has long advocated for the city to meet the requirements of the consent decree. We retained an expert to scrutinize the city's plan to stop sewer overflows and regularly met with city officials to track progress. We were pleased when the city increased public participation opportunities and imposed an aggressive schedule to complete the Headworks Project.

Baltimore's sewage overflows have long been a contentious issue throughout the Bay watershed, with watermen and other affected groups often urging the city and elected officials to fix the problem.

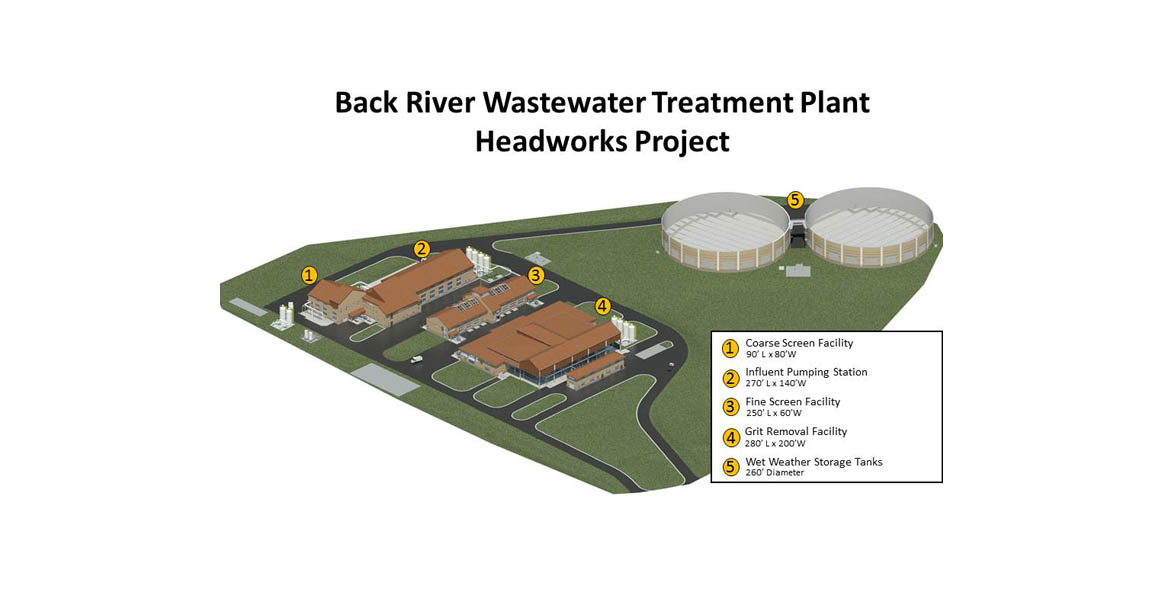

Baltimore City Department of Public Works

The new upgrades to the Back River Wastewater Treatment Plant are expected to solve a long-term problem that plagued Baltimore's sewer infrastructure. The pipes leading into the plant were designed poorly when built more than 100 years ago. Those pipes used gravity to transport wastewater to the plant, but were susceptible to backups of up to 10 miles in wet weather. When too much water overloaded the antiquated system, the excess wastewater dumped into outflows on the Jones Falls upstream from Penn Station and flowed into the Baltimore Harbor and Chesapeake Bay.

These overflows have been significant—the city reported tens of millions of gallons of sewage overflows in 2020 and 2019, according to data posted on the city's website.

With new pumps and storage tanks capable of holding 36 million gallons of wastewater, among other upgrades, the new headworks should solve the hydraulic issues that caused extensive backups.

Now, when wet weather causes heavy flows into the treatment plant, the excess wastewater drops into a chamber where it gets sucked up by the pumps into the plant or diverted into the holding tanks until the plant can treat the water.

"At the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, we were often frustrated with how long it took to upgrade this integral part of Baltimore's sewer system, but we're pleased to see this project come online," said CBF Maryland Executive Director Josh Kurtz. "We'll continue to monitor its effectiveness and ensure it works as city officials expect."

The upgrades should also help prevent residential sewer overflows, which send sewage up through toilets and create significant messes inside homes. CBF has worked with Baltimore residents to help them navigate city programs designed to refund the cost and time it took them to clean up homes fouled by sewage overflows.

While the Headworks Project will help improve water quality, especially in the area around Baltimore City, it's just a small part of the overall Chesapeake Bay cleanup. Cities, counties, states, and the wide coalition of clean water advocates must continue to work together to incrementally reduce pollutants from all sources to restore the Chesapeake Bay and protect its natural resources.