Arrrr! From Pirates of the Caribbean to Captain Hook, pirates in pop culture have always enticed us to hoist the Jolly Roger and sail away from our landlubber ways. But did ye know there were once—maybe still are—pirates on our very own Chesapeake Bay?

Grab your grog and join us as we learn about these swashbuckling men and women from author and historian Dr. Jamie Goodall, whose new book Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay: From the Colonial Era to the Oyster Wars will make anyone want to try out their sea legs.

Q: Pop culture has swayed the public opinion of what a pirate is, but in terms of your book and the history of pirates in the Bay, could you define what exactly is a pirate is?

Dr. Goodall: From the Elizabethan Sea Dogs through the so-called “Golden Age” of piracy, commerce raiders have maintained a prominent place in people’s imaginations. Depending on who you were and which side of a conflict you found yourself on, pirates were called many things: “corsairs,” “buccaneers,” “privateers,” or even “rebels.” I understand pirates to be those whose primary purpose was to disrupt commerce, specifically via waterways like oceans, seas, and rivers. But pirates also operated on land, like the way Sir Henry Morgan sacked Portobello.

Privateers were, really, no different from pirates except that they held a letter of marque giving them legitimacy as legal actors of their government. Privateers very often crossed the line into piracy, attacking vessels of nations their letter of marque did not cover. In a letter of marque, the name of the enemy nation (or nations) was clearly stated and all prizes were to be brought before an Admiralty Court to determine its status. There were supposed to be heavy penalties if a privateer seized the ship of a neutral nation. But many privateers felt it better to ask for forgiveness than permission.

Q: What got you interested in the pirates of the Chesapeake Bay specifically?

Dr. Goodall: My doctoral research focused on pirates in the Atlantic world, primarily the Caribbean. I hadn’t given much thought to pirates in the Chesapeake Bay until I moved to Maryland in 2015. During a history conference in Baltimore, I met an editor for The History Press and she loved my research focus. So she asked if I’d be interested in working on a book that focused on the Chesapeake Bay region. Since I was living in Maryland, I thought it would make the perfect case study of pirates.

Oyster pirates are depicted dredging at night. From “The Oyster War in Chesapeake Bay,” Harper’s Weekly, 1884.

Library of Congress

Q: How early were pirates documented in the Chesapeake Bay? What were they doing in the Bay at that time?

Dr. Goodall: Much of the evidence we have for pirates, particularly in the Chesapeake Bay region, comes from official correspondence in the Colonial Office Records. But we also have pirate trial transcripts, depositions from suspected pirates, and even material culture evidence. Pirates in the Chesapeake were part of a much larger phenomenon, what many referred to as a brotherhood, or the Brethren of the Coast. This was a very loose coalition of pirates (and privateers) with bases in Tortuga, Nassau, and Port Royal. They operated throughout the wider Atlantic world and the Indian Ocean. So pirates in the Chesapeake Bay operated very similarly to those who operated in the wider Atlantic world. They worked to disrupt the commerce coming in and out of the Bay. The economy of the Chesapeake was based on the region’s accessibility, which made it a convenient space for importing and exporting goods and people across the Atlantic.

Q: What made the Bay so beloved by pirates for piracy?

Dr. Goodall: The Chesapeake Bay region encompasses both Maryland and Virginia, and the Bay extends 200 miles from Havre de Grace, MD in the north to Virginia Beach, VA in the south. Piracy affected a number of locations big and small in the whole of the Chesapeake. When looking at Maryland specifically, we can turn to places like Palmer’s Island, Annapolis, Baltimore, St. Mary’s City, the Eastern Shore, and Fell’s Point just to name a few. Bringing Virginia into our study, we can look particularly at Richmond, Williamsburg, Blackbeard’s Point, and Chincoteague. The Bay was particularly useful to pirates due to the many inlets, islets, and rivers that afforded them a means of escape from the vessels sent to capture them. Pirates tended to use ships that had shallower drafts and were smaller in size, making them more maneuverable in shallow waters.

Aside from the profitability of attacking ships carrying tobacco and other commercial goods throughout the Atlantic world, war helped increase the presence of pirates in the Chesapeake region. The War of the League of Augsburg (1689-1697) and the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1713) widely disrupted trans-Atlantic trade, including Chesapeake exports of tobacco to London. A stagnation in the Chesapeake’s economy meant that pirates afforded local residents, merchants, and government officials the ability to import European goods they previously couldn’t afford or were unable to acquire during war. It was a pattern that perpetuated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries during periods of incessant warfare.

Q: Do you have any favorite pirates that frequented the Chesapeake Bay?

Dr. Goodall: One of my favorite pirates to operate out of the Chesapeake is Louis Guittar, a Frenchman who attacked merchant vessels coming out of Lynnhaven Bay inlet. Guittar was attacking vessels laden with valuable goods as they came and went, including a Barbadian sugar vessel. He had also taken many locals hostage. His vessel, La Paix (The Peace), was 200 tons, held at least 20 guns, and nearly 150 men. And it was feared that unless swift action was taken, the pirate would do more harm and continue to increase his strength.

Before he was captured, Guittar seized no fewer than three vessels in a single week. On April 17th he had taken the pink, Baltimore. The pirates kept the ship, killing one man and kidnapping the other twelve men on board. Guittar kept six men on the pink along with sixteen members of his crew and brought the other six on board the La Paix. The very next day, the men took a sloop called the George and imprisoned its captain and crew. They plundered the vessel of its goods, including £200 in gold and added it to their growing fleet. And on April 23rd, Guittar and his men seized the Pennsylvania Merchant, an 80-ton vessel bound from London to Philadelphia. Following a familiar pattern, the pirates boarded the ship, kidnapped all 31 crewmembers, and rifled the ship. They took personal belongings from the crew, including a green and gold enameled watch, and all the sails, rigging, spars, etc. This time, however, they burned the ship. In the following weeks, they continued their pillaging pattern, attacking the Indian King, the Friendship of Belfast, the Nicholason, and an unknown pink. While they didn’t keep all of the ships as part of their fleet, they now had five new vessels in addition to La Paix.

Guittar ultimately met a grisly end. The King went on a hanging spree. Many of those hanging in the winter and spring of 1701 were the Frenchmen of the La Paix. In a single day, Guittar and 23 of his men were hanged. Clearly the King was feeling less than charitable.

Q: What do you feel is the biggest misconception about pirates?

Dr. Goodall: Many of the misconceptions we have about pirates comes from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, particularly the 1950 film rendition. Perhaps the biggest misconception is that pirates talked a certain way. Many of the phrases we associate with pirates were made up by Stevenson and popularized by Robert Newton who played Long John Silver. The accent Newton used was, in fact, an exaggerated version of his native accent. He was raised in Dorset, not far from Bristol, so he was familiar with the English West Country farmer’s accent. He thought his version of this accent would bring additional flair to the already popular pirate flicks, and he employed it with great success.

Editor’s note: Please ignore the language we used in the intro.

Q: Were there any female pirates or Black pirates in the Bay?

Dr. Goodall: As far as female pirates in the Chesapeake, there’s very little evidence that they existed. But one of my favorite stories is about the women of the Dancing Molly. During the Oyster Wars, still smarting from losing over fifty oyster pirate ships, Virginia’s Governor Cameron was determined that this raid would not be a wasted effort. The men of the Pamlico witnessed another potential pirate vessel, the Dancing Molly. The governor hoped that this attack would be executed easily seeing that the men of the dredge boat were on shore searching for wood. What he didn’t know was that the captain had brought his wife and two daughters along, who remained inside the dredge boat while the men were ashore. All three of the women were skilled seafarers themselves. So when the Pamlico began to approach the Dancing Molly, the women ignored the warning shots, took advantage of the winds in their favor, and escaped to Maryland. According to the Norfolk Virginian, spectators along the Virginia shore “really wished for the safety of the tiny craft,” after they realized it was crewed by three women, “and when the Dancing Molly got safely out the group of Virginians chivalrously gave three cheers for the pirate's wife and daughters.” This was a particularly humiliating defeat for the governor.

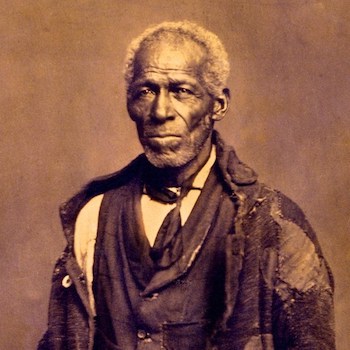

Photographic portrait of George Roberts by Daniel and David Bendann.

Maryland Historical Society

There were many Black pirates and privateers in the bay. One of the men to serve on the Chasseur as a gunner during their famous blockade of England in August 1814 during the War of 1812 was a free Black man named George R. Roberts. Captain Boyle noted that Roberts “displayed the most intrepid courage and daring,” and later was “highly thought of by the citizen-soldiery” of Baltimore. He was even one of the few defenders of Baltimore to have his portrait taken by a photographer. Before serving on the Chasseur, Roberts was a member of Captain Richard Moon’s privateer Sarah Ann.

Roberts wasn’t the only Black Marylander to serve as a privateer in the War of 1812. He’s joined by men like Percy Sullivan and Henry James of the Tartar, Charles Ball who fought at the Battles of St. Leonard’s Creek, Bladensburg, and Baltimore with the U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla, and Gabriel Roulson and Caesar Wentworth who served respectfully as a landsman and cook in the U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla in 1814. In addition to serving aboard a privateer ship, there were also countless mechanics who kept the vessels afloat, like George Anderson, Solomon Johnson, Elisha Rody, & Jack Murray. Each man served in the Fell’s Point shipyards as naval mechanics. Murray even became one of the celebrated Old Defenders’ of Baltimore.

Q: The Chesapeake Bay and its many ports played a large part in the Atlantic slave trade. Did Chesapeake pirates play a role in it as well?

Dr. Goodall: Absolutely. Piracy and slavery were intimately tied together. Some pirates would free enslaved peoples they came across during their exploits, sometimes even allowing Black men to join their pirate crews. Other pirates actively participated in the trade of enslaved peoples. The Chesapeake Bay relied very heavily on the forced labor of enslaved Black men, women, and children. And many pirates were more than willing to supply the Chesapeake Bay with that enslaved labor.

Q: If you know the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, you know that restoring oyster reefs, decimated by disease and historic overfishing, is one of our main objectives to help save the Bay. But we heard that at one point there was an “Oyster War” that pirates may have played a part in. Could you tell us a little about what caused this war and how pirates played a role in it?

Dr. Goodall: Oyster fishing was good business. So much so fishermen from as far away as New England flocked to the Bay, leading to an over-abundance of competition. The Maryland waters of the Chesapeake Bay were particularly ideal for growing oysters because of the vast expanses, suitable temperature, and salinity level. The area’s waters also had few oyster predators and were free of the parasites that often caused common oyster diseases. Maryland wanted to stop the threat of outside competition and in 1830 they passed a series of laws limiting Maryland oyster harvesting to state residents only. Some say that this was the start of the so-called “Oyster Wars.”

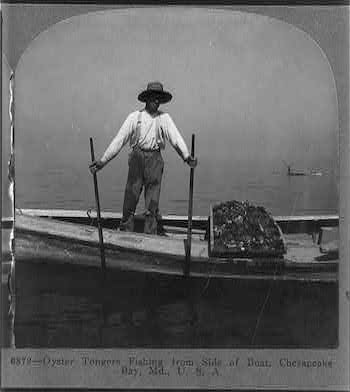

Oyster tongers fishing from side of boat, Chesapeake Bay, circa 1905.

Library of Congress

In Maryland and Virginia, anyone who violated these oyster laws became known in the press and by the public as “oyster pirates.” There were two types of oyster catching: tonging and dredging. Those used the tonging method worked in shallower waters and their boats generally carried only a couple of men. One of them would use long tongs to gather the oysters and one would cull them. Maryland officials also outlawed dredging, a harvesting method considered harmful to the Bay, although Virginia continued to permit it until 1879. Dredgers used larger boats and worked deeper waters where they could harvest more in the basketlike scoops they dragged over the oyster beds. Dredging often left so few oysters that they could not naturally reproduce fast enough. So when out-of-state watermen brought their dredges to the Chesapeake, Maryland lawmakers were concerned.

Q: Any last fun facts about the pirates of the Chesapeake Bay?

Dr. Goodall: Perhaps the greatest rumor of buried treasure in the Chesapeake is that of Charles Wilson. Legend has it that Wilson was a pirate who had a hideout at Woody Knoll in Worcester County, Maryland. He also had a hideout at Assateague. But it was at Chincoteague that he reportedly buried his treasure, worth perhaps upwards of $4 million today. In a letter attributed to Wilson, he writes to his brother:

There are three creeks lying 100 paces or more north of the second inlet above Chincoteague Island, Virginia, which is at the Southward end of the peninsula. At the head of the third creek to the northward is a bluff facing the Atlantic Ocean with three cedar trees growing on it, each about 1 ⅓ yards apart. Between the trees I buried in ten iron-bound chests, bars of silver, gold, diamonds, and jewels to the sum of 200,000 pounds sterling. Go to the Woody Knoll secretly and remove the treasure.

The letter reads more like a riddle than a map to buried treasure. But it hasn’t stopped treasure seekers from around the Chesapeake for attempting to get their hands on Pirate Wilson’s buried hoard!

Learn more about the Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay in Dr. Goodall’s Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay: From the Colonial Era to the Oyster Wars.

Jamie L.H. Goodall, PhD, is a Staff Historian with the U.S. Army Center of Military History. She has a PhD in History from The Ohio State University with specializations in Atlantic World, Early American, and Military histories. She is also a first-generation college student. Her publications include a journal article, “Tippling Houses, Rum Shops, & Taverns: How Alcohol Fueled Informal Commercial Networks and Knowledge Exchange in the West Indies” in the Journal of Maritime History and Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay: A Brief History of Piracy in Maryland and Virginia. She is currently working on a manuscript about pirates in the Mid-Atlantic.