"I was born on the water . . . in a sense," says Nathaniel ("Nat") M. Jones on a dripping August day. The air outside is thick with that high summer humidity that is so familiar to Virginians. Inside, in the modest, one-story rancher off Jones Drive in Weems, Virginia, where Jones has lived all his life, it's ripe with stories of the water. A lifelong Chesapeake waterman, father of nine, World War II vet, teacher, carpenter, farmer, and husband, Jones’ life is nothing if not rich.

Boyhood on the Northern Neck

Born in 1926 along Carter's Creek, the 92-year-old has always had brackish waters in his veins. And it's easy to understand why. He recalls days as a boy, rising early to fish with his Uncle Clarence for crabs. Clarence would use a trot line to catch hard shells while eight-year-old Jones would go wading into Taylor's Creek, hunting for soft shells. He'd sell them for 10 cents a dozen, often beating out his uncle. "I'd make more money than he would!” Jones beams from the comfort of his living room armchair. When he wasn't at school, soft-shelling, swimming across the Corrotoman, or working on neighboring Holly Haven Farm on Fridays and Saturdays, Jones would watch his Uncle Jerry (AKA "Uncle Moody") with awe as he carved cedar trees into poles and go pole fishing.

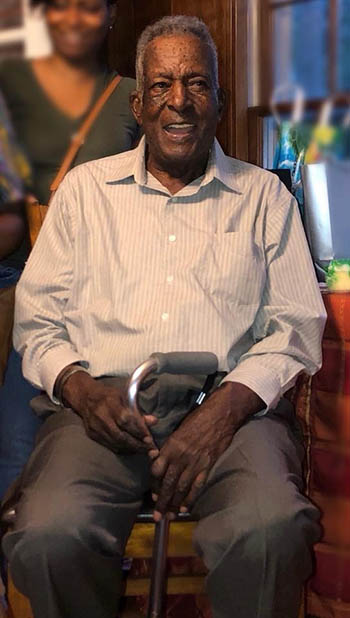

Life-long waterman Nat Jones celebrating his 92nd birthday with family and friends in Richmond, Virginia, in September of 2018.

Otis Jones.

Uncle Moody's namesake—and Jones' grandfather—Jerry Carter used to haul freight in the 1930s up and down the Bay, from Norfolk to Baltimore, in his two-engine, 14-horsepower boat named the L.T. BUGGS. Even in the dark, with no lights on the boat, he could navigate these waters. It just came naturally to him. "He was just gifted I guess," says Jones. When Carter wasn’t on the water, he grew watermelons and cucumbers in his backyard—"the biggest kinds you've ever seen in your life"—and sold them to local factories. He didn’t work for anyone and was completely self-sufficient in an age when doing so as a black male in the south was nearly unheard of. "He didn't work for nobody but himself."

At age 13, Jones learned to hang and splice rope from the older watermen and craftsmen who worked out of a nearby net house. These nets were crafted out of cotton at that time (before discovering rot-resistant nylon) and used on the many boats headed out of Reedville, Virginia, to catch menhaden—a forage fish that many call "the most important fish in the sea."

Jones was eager to join his father on the menhaden boats, but his father refused, insisting that he finish school first. "He didn't want me to come up like he did," Jones says. "He wanted me to learn to read and write." Later, Jones and his sisters would teach their father—who only had a second-grade education—to read. For now, Jones would have to settle for intricately crafting and mending fishing nets using a bunt needle. “There was a lot of headache in it,” he says.

"Nothing but a Pile of Bricks"

At 17, in his final year of high school, Jones was drafted and sent to Europe. It was 1944 and the world was all aflame. Jones became a combat engineer for the army and was shipped across the English Channel to Normandy in the follow-up to D-Day. He still remembers marching through France to southern Germany, building bridges ahead of the infantry and coming face to face with indescribable devastation: "It was nothing but a pile of bricks," he says.

After the war, he remained in the army in Bremen, Germany, where he taught math to first- and second-grade German children. Even now, Jones is able to recite geometrical terms at the drop of a hat: "A circle is a closed figure bounded by curved lines with all points equal distant from the center point within. That's the definition of a circle," he says with a comforting exactness and certainty that was especially needed in post-World War II Europe. "There's no other definition."

Jones remembers racing cars on the Autobahn and exploring Holland and Switzerland, but after roughly two years on the other side of the Atlantic he was called home to Virginia’s Northern Neck when his mother took ill.

"There was a lot of headache in it," waterman Nathanial "Nat" Jones says of using a bunt needle to mend and craft fishing nets to catch menhaden.

Emmy Nicklin/CBF Staff.

"Bye Bye Sweet Rossanna"

When he returned home, Jones felt that all-too-familiar pull of the water. He started working as a rigger on one of Zapata-Haynie's menhaden boats out of Reedville (Jones would eventually work for all five of the different menhaden companies based in Reedville at that time). "I was the one who pushed myself into it," he says. "I was just interested in it that’s all. I respect the water. I loved the water, all the time. And still love it.” Jones would spend five days out at a time on the Chesapeake and six months of the year down in the Gulf off Louisiana. He'd serve as a rigger pulling up heavy nets, chock-full of fish, alongside a dozen other men. They’d sing sea chanties to keep in rhythm with each other as they heaved the net over the side of the ship:

"Bye bye bye sweet Rossanne

bye bye sweet rossanna

I thought I heard my loving baby say

I won’t be home tomorrow"

Eventually, after years of hard, physical labor, Jones became the cook on the boat, serving up fried chicken and potatoes or shrimp and grits depending on where the boat was stationed at the time—off the Carolinas, in the Chesapeake, or down in the Gulf. Even at 92, he continues to cook today, feasting on his favorite oyster cakes—pancake batter, an egg, and a pint of oysters all fried together—the very morning that I arrive.

When he grew tired of cooking, Jones became a pilot, acing the rigorous exam in one try. As a pilot, he'd navigate the shipping channels as the captain mapped out the boat's itinerary. "You had to run those boats up and down Chesapeake Bay at night and even in the Gulf," Jones says. "Everyone's asleep. [It was] lots of strain, lots of stress. Hard on your eyes, I can tell you that. That's why I can half see now. One mistake and everyone's life is in your hands."

In the winter months, when he wasn't working on the menhaden boats, Jones would tong for oysters out of Colonial Beach on the Potomac. The water was rough and the days cold, but Jones wouldn’t have it any other way. "I didn't mind the cold weather," he says. "Colder it got, better I got. Harder I worked," he says. With heavy 22-foot-long tonging poles, he'd tong 16-20 bushels of oysters every day, getting $8-10 per bushel. “I’ll tell you one thing, I’ve been in rough times out there in that river,” says Jones of braving record low temperatures and dodging ice sheets in his boat the Little Nona, "but I loved it, and I liked that money!"

Chesapeake waterman Nat Jones has lived off Jones Drive in Weems, Virginia, all his life. He grew up in the house next door to where he lives now with uncles, aunts, grandparents, and even his wife's family in houses nearby. Here, clad in the hat given to him by great grandson and Harvard sophomore Mario Hashin, Jones stands next to a pair of his old oyster tongs.

Emmy Nicklin/CBF Staff.

"All My Work Is Just the Water"

Despite all his years working the water, catching crabs, netting menhaden, and tonging oysters, Jones—like his father before him—discouraged his children from following him into the fishing business. Education was just too important. Instead, his children went on to become a pharmacist turned Baptist minister, former Principal, Banker, juvenile probation officer, IBM executive, Chesapeake Bay Foundation board member, and more.

But though his children don't know the Bay quite like Jones does, they share in an unwavering love of and appreciation for the water. It's inevitable with a father like Jones. "Everything around here, in some sort of form, shape, or fashion, is connected back to the water," says son Eric. And though, as Eric continues to reflect, the wooden workboats and oyster houses that were once synonymous with this part of the world are one by one disappearing, the connection to and pull of the water is no less palpable.

Especially to Jones.

"I miss it in a sense," says Jones of his work. "But I had worked enough in my life. Hard work, too." Now as he sits in his faded armchair, surrounded by books and letters and graduation pictures of his grandchildren (he and wife of 70 years, Marvis, have 23, plus 43 great grandchildren and four great-great grandchildren,) Jones reflects on his time on the Chesapeake with a contentment and utter gratitude that’s very often hard to find in this life: “I’ve been through some rough times, you know, but thank God I'm still here, that’s a blessing . . . I loved fishing. I still love it. And I just love the water. All my work is just the water. Something you've been doing all your life, you just get accustomed to it."

UPDATE: Nat Jones passed away on April 27, 2021. He led a rich and wonderful life on the water. He will be missed.