September 24, 2024—In a significant reversal of their June vote, Virginia state regulators killed the possibility of opening the blue crab winter harvest for the 2024/2025 season. Read press release

What Are Blue Crabs?

Known as the "beautiful swimmer," blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus, are the most iconic Chesapeake Bay species. They are found in coastal waters along the Atlantic Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico in the United States, although their range stretches as far south as Argentina in South America.

Blue crabs have bright blue claws and four pairs of legs—the rearmost of which have paddle-like ‘fins’ that allow them to swim throughout the water column. They eat a range of foods including mussels, oysters, small crustaceans, and decaying plant and animal matter, and they are often found in the Bay’s underwater grass beds. These grass beds form a crucial habitat that provides food, shelter, and protection when crabs are young and when they mate and molt (shed their shell).

Depending on the time of year, blue crabs can be found in different parts of the Bay. They are most active from spring through fall, but commonly burrow into the Bay’s bottom sediments during winter to wait out the cold. Mating often occurs in shallower waters that support underwater grass beds. Once they have mated, female crabs migrate to the saltier waters at the mouth of the Bay to spawn. The tiny blue crab larvae begin their lives in the ocean, growing and molting several times before they return to the Bay. It takes a year to 18 months for a crab to reach maturity.

Why Are Blue Crabs Important to the Chesapeake Bay?

Blue crabs support one of the Bay’s most valuable commercial fisheries and a large recreational fishery. In Maryland alone, commercial landings of blue crab have topped $45 million in dockside value annually for the past decade—far more than oysters and striped bass combined. In Virginia, the commercial harvest value has ranged from $22 million to $38 million annually. Moreover, crabs continue to hold great cultural significance in the watershed. Picking steamed crabs has reached the level of an artform in many Chesapeake Bay communities, where they are often enjoyed for summer holidays and at family gatherings, and crab cakes are a staple of both restaurants and home cooking.

Humans aren’t alone in our love of crabs. Blue crabs serve many important roles in the Bay food web. As larvae they are preyed upon by numerous filter-feeders, such as menhaden. As they grow older, crabs feed upon a variety of smaller bivalves that live on the Bay floor. Eventually, many crabs are then preyed upon by larger fish and birds. Some of the more common Bay species that eat blue crabs include red drum, croaker, blue catfish and cobia. In fact, cobia are such voracious predators of blue crabs they are sometimes referred to as “crabeaters.”. And, yes, the tales of cannibalism are true—blue crabs will eat other blue crabs.

How Are Chesapeake Bay Blue Crabs Doing?

After falling to record low numbers in 2022, the Chesapeake Bay blue crab population showed modest signs of improvement in the 2023 Blue Crab Winter Dredge Survey, released May 18, 2023. The 2024 survey showed a slight decline, but still well above those of 2022.

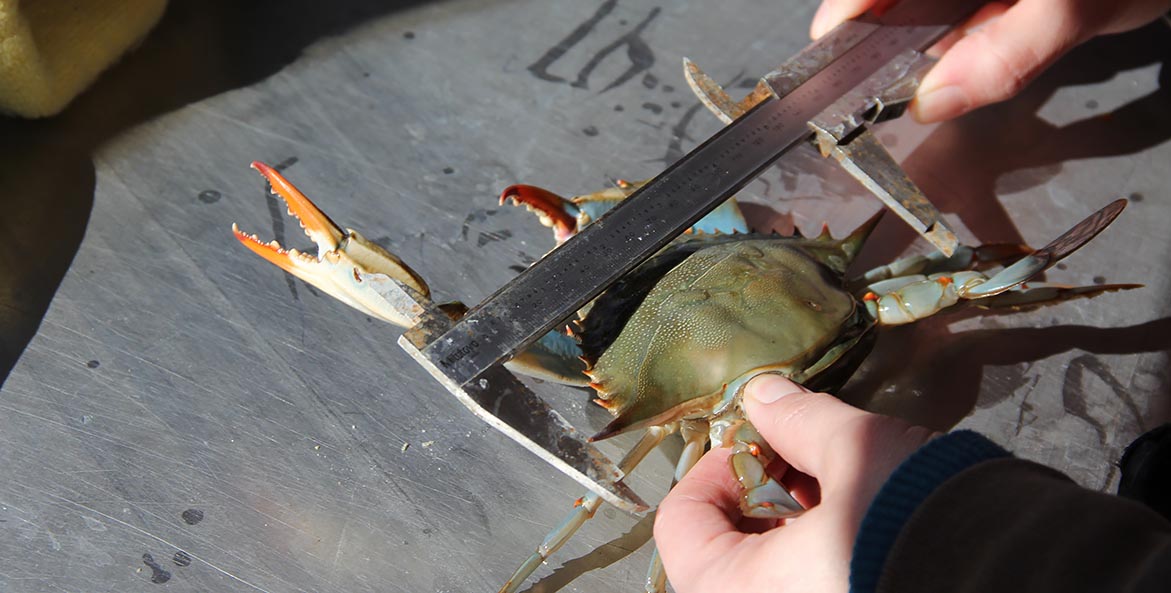

Each winter, Maryland and Virginia partner on the scientific survey, which produces an estimate of the number of blue crabs in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. This is one of the most comprehensive surveys of any species in the Bay, dating back more than 30 years. The survey is usually conducted December through March, and preliminary results are released around late April or May. A comprehensive review of those results is completed annually by the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee and released in early July.

The blue crab population fluctuates annually based on a variety of factors, including reproductive success, weather, predation, and harvest. Estimated total crab abundance decreased from 323 million in 2023 to 317 million. While considered "stable" by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, there is still plenty of cause for caution. Results highlight the importance of protecting spawning females as well as considering precautionary measures to protect juveniles so they can grow to maturity and spawn. The survey follows three consecutive years of declines in the coverage of underwater grasses, one of the most important habitats for blue crabs in the Chesapeake Bay. It is likely that the loss of grasses is contributing to some of the blue crab's struggles, along with water quality challenges and predation by invasive blue catfish.

Fisheries regulators and scientists are currently working on a new stock assessment that will help to identify the key ecosystem factors influencing blue crab recruitment and survival so we can help ensure a healthy blue crab population in the future. This comprehensive effort is expected to be completed in late 2024.

What Are the Threats to Chesapeake Bay Blue Crabs?

The blue crab is one of the more resilient Chesapeake Bay species, but it faces constant challenges to survive: predators, dead zones of low oxygen, vanishing habitat, and at times cold winters, to name a few.

Especially for young and female crabs, underwater grasses represent one of the most important habitats for foraging and protection. But the Bay’s grass beds are vulnerable to both extreme flows of fresh water from heavy rainstorms and warming temperatures that are linked to climate change. High flows of fresh water wash more pollution into the Bay, affecting water clarity and blocking sunlight that grasses need to survive, and warming water temperatures can create further stress.

Crab habitat is also affected by what is commonly termed “dead zones”— areas of little or no oxygen that rob blue crabs of both food sources and areas to hide from predators. Dead zones are caused by excessive nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in the water, which feeds large algal blooms. Dead zones form when the algae die, sink to the bottom, and are decomposed by bacteria—a process that strips dissolved oxygen from the surrounding water. Dense algal blooms also block sunlight, which prevents underwater grasses from growing.

An increasingly problematic predator is the invasive blue catfish. Introduced to the region in the 1970s, their growing numbers throughout the Bay have raised concern about their potential impact on important native species like blue crabs and menhaden.

Fishing pressure also has an impact on the blue crab population. As the Bay’s oyster populations declined drastically in the 1980s, watermen began extending their crabbing efforts much later into the fall, the time they normally would have shifted to oystering. A decade or so later, the crab population had been cut in half to around 300 million. Not only was the blue crab population itself depleted, so too were the oyster reefs and underwater grasses that provide crabs with food, shelter, and oxygen. New science-based guidelines were established in 2008, focusing on a reduction of the catch of female crabs in order to ensure sufficient spawning.

How Is the Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab Fishery Managed?

In 2022, Maryland, Virginia, and the Potomac River Fisheries Commission adopted a goal to reach 196 million spawning-age female crabs in the population (known as the target) and to keep the number of spawning-age female crabs from falling below 72.5 million (the threshold). These goals are achieved through fishery management actions that define regulations such as harvest limits, crabbing seasons, size limits, gear restrictions, and others. The number of adult female crabs increased in 2023 to 152 million, below the target but higher than the period prior to 2008 when the blue crab resource was declared a fishery disaster.

The ultimate goal of management is to create a stable blue crab population. Currently the Bay’s blue crab population is truncated—meaning we catch crabs so quickly there are very few crabs left that are bigger than the legal harvest size. The fishery is therefore very dependent on the survival of young crabs from one year to the next, creating instability as the population may fluctuate significantly. Having more, older crabs in the population increases the reproductive potential, providing a buffer that helps stabilize the population even in years when poor weather conditions or other factors negatively impact the population. Larger crabs, on average, are also more valuable in the market, and therefore result in better economic returns for the crabber.

It is therefore essential for Maryland and Virginia to continue applying the science-based fishery management guidelines adopted in 2008.

What Can We Do to Help Blue Crabs in the Chesapeake Bay?

In addition to science-based management, improving water quality and restoring habitats such as grass beds and oyster reefs are two things that are critical for helping the Bay’s blue crabs.

The Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint, the science-based plan to restore the Bay, requires each of the six Bay states and the District of Columbia to put practices in place by 2025 that will reduce nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. Ensuring the Blueprint is fully implemented on time will significantly reduce the polluted runoff from farms, cities, and other sources that creates the Bay’s low-oxygen dead zone and impedes the growth of the underwater grass beds where crabs live.

Better stormwater management, through practices such as forested stream buffers and green infrastructure, can also help mitigate weather extremes and improve water quality. And reducing harmful greenhouse gas emissions and implementing practices that keep carbon out of the atmosphere—including regenerative agriculture practices—will help reduce climate change and its impacts on blue crab habitat.

News & Stories

-

Bonjour Blue Crabs: Low in Chesapeake, On the Rise Elsewhere

June 14, 2024

While the recent blue crab survey showed numbers remain low for blue crabs in the Chesapeake, this iconic Bay species is showing up in wildly unexpected places across the globe, including France, Croatia, and Maine.

-

Chesapeake Blue Crab Numbers Remain Low Despite Signs of Improvement

May 22, 2024

The Chesapeake Bay blue crab population showed some signs of improvement from a previous 33-year low in recent survey results, but concerns remain about their overall decline.

-

Save the Bay News: Restoration, Wetlands, and Saving Striped Bass

June 29, 2023

Progress toward clean water includes the need for a greater focus on the Bay's 'living resources,' such as blue crabs and striped bass, as well as placing more emphasis on the places and pollution that most affect the Bay's human communities.

-

VMRC Takes Action on Blue Crabs, Striped Bass

June 27, 2023

The recovery of both blue crabs and striped bass depends on careful management of the fishery and accelerating work to improve water quality and habitat in the Bay.

-

What's Going on with the Chesapeake Bay's Blue Crabs?

June 13, 2023

After falling to record lows in 2022, blue crabs are on the rise—albeit a modest one. CBF scientist Chris Moore explains why there's still reason for caution.

| Items 6 - 10 of 20 | Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Next |

Multimedia

-

July: Grass Shrimp Don't Have Many Friends

21 Jul 2021Join John Page Williams as he shares anglers' secrets for finding grass shrimp and how to use them to catch your preferred fin fish. Not interested in fishing? They also make a great appetizer!

-

July: Traveling Crabs

14 Jul 2021Join John Page Williams as he reveals how tropical storm Agnes led to a better understanding of the traveling life of baby Chesapeake Bay blue crabs.

-

June: For Soft-Crabbers, Summer Is a Busy Season

02 Jun 2021During a 24- to 30-month life span, a blue crab will molt over 20 times. What goes on inside the animal to trigger the shedding of it's entire shell? And what does it mean for the crab, and for the crabbers who do business in soft crabs? John Page Williams sheds light on both the human and critter stories.

| Items 4 - 6 of 6 | Previous | 1 | 2 |