As communities across the Commonwealth face pressure to update old stormwater infrastructure and accommodate growth, there is great opportunity to design stormwater systems that revitalize local communities and economies, reduce flooding, restore health to our rivers and streams, and support a vibrant quality of life.

The Problem with Stormwater Runoff in Pennsylvania

The next time it rains, watch the water move from your roof and your driveway down the street. Some of it soaks into the soil to become groundwater. Some of it evaporates into the air. But most of it is on its way to the nearest stream, lake, river, or wetland. It's the same for water from snowmelt, sprinklers, hoses, and other sources.

This water is referred to as stormwater runoff. As it flows over the land, it picks up and carries pollutants, litter, and sediments (soil). Along the way, excess fertilizers and pesticides, pet waste, motor oil and antifreeze, cigarette butts, and other debris on the streets all can hitch a ride.

Chesapeake Bay Foundation

Stormwater runoff also draws heat from concrete and asphalt pavement as it travels, causing river and stream temperatures to rise. This creates multiple problems for our waterways. Because hot water can hold less oxygen than cold water, aquatic creatures that require high levels of oxygen find it harder to survive. Plus, critters like Pennsylvania's iconic brook trout and our new state amphibian, the Eastern hellbender, like cold, clean water.

Runoff also causes sudden increases in the amount and speed of water flowing into streams, resulting in increased erosion of streambanks and increasing localized flooding.

Based on scientific studies, as of 2020 more than 5,200 miles of Pennsylvania's rivers and streams were considered impaired¹ due to stormwater runoff. Stormwater is also identified as a significant, and growing, source of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution from Pennsylvania that ends up in the Chesapeake Bay, where it contributes to harmful algae blooms. When the blooms die and decompose, they create low-oxygen "dead zones " where fish, oysters, and crabs cannot survive.

What is Stormwater Management?

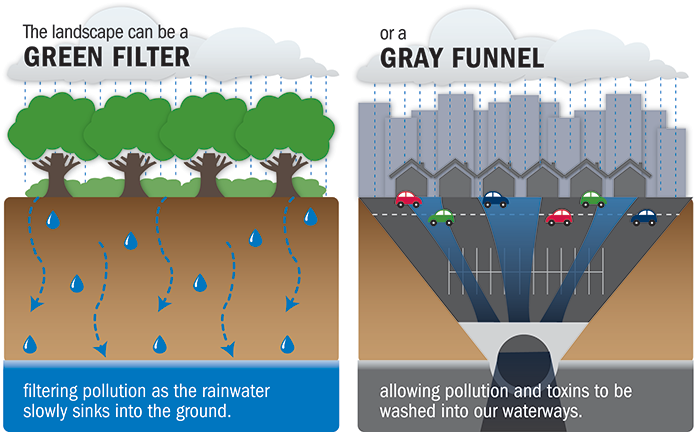

Historically, communities were designed to get rid of stormwater runoff as quickly as possible. This often meant building gutters and underground drainage systems with concrete and pipes to funnel the water off streets and into storm sewers. Storm sewers carry runoff—and all of the pollution it contains—directly and completely untreated into rivers and streams. Many of the older communities in Pennsylvania also combined human sewage with stormwater into a single system.

Under the Clean Water Act, cities and urban areas must obtain permits that limit the amount of pollution they are allowed to discharge through their storm sewer systems.

Tom Pelton/CBF Staff

According to state records, Pennsylvania has seen a 10 percent increase in precipitation since the 1970s². By 2050, estimates are precipitation will increase another 8 percent. This increase in short duration, high intensity rainfall threatens to overwhelm existing stormwater systems and increase stream pollution.

Communities can't control the weather—but they can better manage stormwater. The way decision-makers design neighborhoods, streets, and green spaces like parks and urban landscaping can change where and how fast water flows into our streams and rivers. This is known as stormwater management.

Solving the Problem: The Basics

Citizens, planners, engineers, developers, and elected officials all play a critical role in helping to prevent and solve stormwater challenges. The key is to start at the source—with how we use and what we do on the land.

Land-Use Plans and Ordinances

In developing areas, it is cheaper and far better to plan ahead by identifying areas for compact development and protecting open spaces that maintain and mimic the natural water cycle.

Preserving the natural systems that filter, cleanse, and moderate the flow of stormwater runoff saves engineers, builders, and communities the enormous cost and trouble of creating treatment systems, retention ponds, and other artificial means of controlling increased runoff. Local ordinances can limit the creation of hard surfaces and preserve critical habitats, like upland forests, steep slopes, and streamside trees.

Where homes and buildings already exist, cities can help discourage sprawl and the destruction of filtering forests and open spaces by promoting re-development within existing communities and directing new development into areas with existing infrastructure.

Collectively, these practices create a powerful combination often referred to as smart growth.

Nature-Based Management

Communities increasingly recognize the need for infrastructure that slows down, spreads out, and filters stormwater runoff, and that they can accomplish these goals by leveraging the power of nature with strategically placed plants and soil.

Commonly called "green infrastructure," these approaches include rain gardens, street trees, constructed wetlands, wet meadows, permeable pavement, vegetated rooftops, and streamside forests. By mimicking natural systems, these practices:

- Slow water down and allow it to soak into the ground or evaporate into the air, rather than running quickly off hard surfaces like pavement.

- Clean the water by directing it through natural filters, like trees and native plants, that capture pollution.

- Can provide additional benefits to the community, such as beautifying neighborhoods, supporting pollinator species and other important wildlife, creating green spaces for recreation, reducing localized flooding, cleaning the air, and reducing heat islands (urban and suburban developed areas that increase air temperature).

A growing number of communities in the Commonwealth are embracing green infrastructure. Some are even making it an artful addition to their communities.

Lancaster is one example. The city is retrofitting hundreds of city blocks with porous pavement over the next 25 years, redesigning parks to absorb stormwater runoff from adjacent roadways, planting more trees, and encouraging the construction of living roofs. The city estimates these practices will reduce its stormwater runoff by 182 million gallons each year within the first five years alone.

In addition, local governments across Pennsylvania are incorporating these techniques into their stormwater ordinances.

In addition to upgrading Pennsylvania's first wastewater treatment plant to meet nutrient-removal requirements, Lancaster is retrofitting streets, parks, and other areas with infrastructure that will significantly reduce stormwater runoff.

Live Green

In addition to upgrading Pennsylvania's first wastewater treatment plant to meet nutrient-removal requirements, Lancaster is retrofitting streets, parks, and other areas with infrastructure that will significantly reduce stormwater runoff.

Live Green

Investing in Solutions

In many ways, Pennsylvania recognized the need and opportunity to address stormwater problems in the aftermath of Hurricane Agnes in the early 1970s. Over the next several decades, as the understanding of stormwater impacts and management grew, state and federal stormwater regulations evolved.

Today, more than 1,000 Pennsylvania local governments are considered "MS4s" and must have permits under the federal Clean Water Act to address stormwater issues. In Pennsylvania's portion of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, there are roughly 360 MS4s.

Many of these communities are required to develop and implement stormwater pollution reduction plans to address water quality problems in local streams. Within the Chesapeake Bay watershed, all MS4s also must include plans for meeting the requirements of the Chesapeake Bay Clean Water Blueprint.

As a result, a growing number of MS4s are seeking ways to not only leverage existing federal and state resources to improve their stormwater systems, but also generate local funding.

Stormwater authority fees (also referred to as stormwater utility fees) are dedicated investments that ensure developed areas, such as homes and businesses, contribute to efforts that reduce the polluted runoff they help create.

Today, roughly 1,700 governments across the United States—25 of them in Pennsylvania, including the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority stormwater fee program that includes 32 local governments—have chosen to establish reasonable stormwater fees. Many more are being considered.

By investing in 21st-century infrastructure, Pennsylvania communities with fees are preparing for a 21st-century economy and higher quality of life.

What We're Doing

CBF is actively working to help Pennsylvania communities address polluted stormwater runoff. Examples include:

- Helping low-income neighborhoods in Harrisburg, Lancaster, and York make the most of opportunities to improve local water quality, reduce flooding, and beautify their communities. These projects include planting new trees, building rain gardens, and installing rain barrels.

- Planting 10 million trees alongside Pennsylvania's streams, streets, and other priority areas by 2025 as part of the Keystone 10 Million Trees Partnership. The trees will help intercept stormwater runoff, keep streams cool and clean, provide shade, and clean up air pollution.

- Urging the passage of the Keystone Tree Fund, which creates a voluntary $3 check-off box on Pennsylvania's driver's license and vehicle registration online applications to support tree planting efforts across the Commonwealth.

- Exploring how farmland can be leveraged to more cost-effectively address stormwater issues and MS4 requirements.

- Providing reliable public information about stormwater.

Find answers to your questions about Pennsylvania stormwater fees.

Additional Resources

CIG—Pennsylvania Offset Partnerships Report; Combined Appendices

¹ Draft 2018 Pennsylvania Integrated Water Quality and Monitoring Report Clean Water Act Section 303(d) and 305(b) Report

² Pennsylvania Climate Action Plan November 20, 2018 (DRAFT)