"The big picture is that controlling runoff makes a community we want to live in. It's greener, healthier, more aesthetically pleasing, and property values go up."

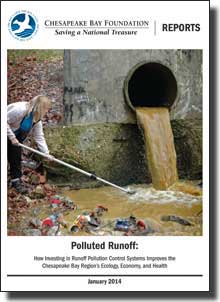

In many communities the stormwater system is simply comprised of curbs and gutters, sewer pipes, or concrete channels, all funneling directly into streams without treatment of any kind. In other instances, while the community may have required the installation of stormwater management devices 10 or 20 years ago, they don't meet modern standards or they simply haven't been maintained. Such situations present a legacy of on-going pollution that requires resolution.

In communities that have poorly performing practices in place, the most cost-effective solution is to bring the existing ponds and other practices up to current standards. In places where there has been no stormwater management at all, solutions can be more expensive and often the best solution may be the development or improvement of a local stormwater utility fee to finance new practices that can be "inserted" by the municipality.

CBF has helped communities across the watershed implement stormwater management projects.

There are several proven strategies communities can implement to absorb runoff and reduce the risk of routine flooding and damage from polluted runoff. They include:

- Trees can be planted to replace the natural filters removed during development.

- Stormwater control ponds can be modified to catch and better filter runoff with shallow water areas, additional plants, and mulch.

-

Outfalls to streams can, in some cases, be improved with the addition of rocks, filtering surfaces, wetlands, and plants.

- Concrete channels can be converted to more natural ditches ("swales") with a series of rock dams ("weirs") and plants to absorb pollutants.

- Streams themselves can sometimes be helped with clean-outs, and channel and bed improvements.

- Roadside vegetated areas ("rain gardens") can be installed, often in ditches atop layers of sand and stones and perforated drainage pipes.

-

Parking lots and street-sides can be altered with "green infrastructure" such as porous pavement and planted, filtering trenches.

- Sewer inlets can be upgraded.

- Communities can create more open, green spaces and install rain gardens to allow water to soak into the soil, for example in or around playgrounds, park areas, schools, and other public buildings.

- Designers can cover roofs with plants that drink up rain ("green roofs").

-

Residents and business owners can install "rain barrels" to collect rain from roof downspouts, and use it on landscaping.

(From top, photos by Scott Alderfer, Underwood and Associates, Tom Pelton/CBF Staff, Kelly O'Neill/CBF Staff)

Projects like these reduce the cost of treating drinking water by preventing pollution in runoff from getting into groundwater and contaminating wells. In some communities, controlling the flow of water during storms can also help prevent risks to human health by reducing sewage overflows onto beaches and into streams where children play, and reduce flooding dangers.

Did you know...

- Apartments with green roofs reduce pollution, lower heating and cooling costs, and are so attractive they command rents 16 percent higher on average than apartments without them. Other runoff control projects that add green to developed landscapes boost residential real estate values by two to five percent, and can lift office rental rates by seven percent.

- Rain gardens filter up to 93 percent of the oil in urban and suburban runoff, vastly reducing pollution to local streams. These gardens also filter up to 90 percent of the toxic metals, 70 percent of the sediment, 30 percent of the phosphorous, and at least 25 percent of the nitrogen pollution(some gardens are capable of removing more).

- Placed at the base of a downspout, a typical rain barrel can hold 55-75 gallons of stormwater runoff from a rooftop, reducing flooding and erosion. They can be found in garden supply centers or easily built.

- A mature leafy tree can intercept 500-1,000 gallons of precipitation a year, and a single mature evergreen can intercept 4,000 gallons a year. At the same time, a mature leafy tree like an oak can "drink up" and transpire more than 40,000 gallons of water a year. The planting of trees and gardens cools urban areas, improves the appearance of neighborhoods, absorbs carbon dioxide, and provides habitat for wildlife. Creating more open spaces, which absorb runoff, also expands recreational opportunities for local residents who want to walk, jog, and play outside.

Learn how to build a rain garden or install a rain barrel and get more ideas for community personal and community projects that can reduce polluted runoff.

Additional information about stormwater management can be found at the following websites:

Chesapeake Stormwater Network

The Center for Watershed Protection

Low Impact Development Center

Low Impact Development Urban Design Tools

As part of our on-going commitment to helping communities reduce stormwater pollution, CBF also provides occasional webinars and other resources.