Contents

What Are Wetlands? Types of Wetlands Why Are Wetlands Important? What Are the Threats to Wetlands? What CBF Is Doing to Protect Wetlands How You Can Help Protect WetlandsWhat Are Wetlands?

Located where land meets water, wetlands—which include marshes, swamps, and bogs—are low-lying areas covered by water some or all of the time. The Chesapeake Bay watershed includes 1.5 million acres of wetlands.

Once disregarded as worthless land, they are now recognized as critical to the protection and restoration of the Bay, its wildlife, and even adjacent lands.

Wetlands can be populated by grasses and other leafy, non-woody plants; woody shrubs; or forests.

Types of Wetlands

There are two categories of wetlands found in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Tidal, also called coastal or estuarine, wetlands, are found along the shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers. These areas fill with water when the tide rises.

Inland or non-tidal wetlands contain fresh water and make up 86 percent of the wetlands in the watershed. Their water levels are affected by precipitation and groundwater. Many are located on floodplains bordering streams, rivers, lakes, and ponds.

Wetlands like those pictured here at Martin National Wildlife Refuge in Maryland provide important habitat for egrets and other wildlife.

Octavio Aburto/iLCP

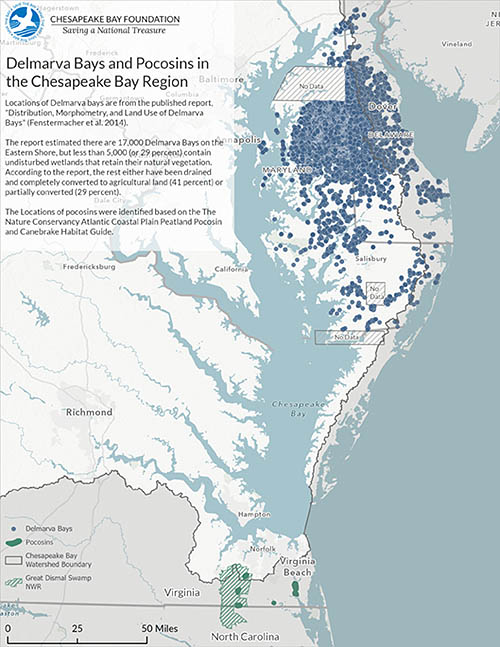

Some non-tidal wetlands are not adjacent to or connected on the surface to other waters, although they are connected below ground. Two types of isolated wetlands that are unique in the Bay region are “Delmarva Bays” and “pocosins.”

Two types of unique, isolated freshwater wetlands are found in the Chesapeake Bay watershed: "Delmarva bays" (also called "Delmarva potholes") and "pocosins" (pronounced "puh-COE-sins"). (Full Map | Printable Map)

Katie Leaverton/CBF Staff

Delmarva Bays (also known as Delmarva Potholes) are shallow, oval-shaped depressions that cover more than 34,500 acres on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia. They can only be found on the Delmarva Peninsula. There are roughly 5,000,

with most clustered around the Delaware-Maryland border.

Isolated bogs with sandy, peat soils known as “pocosins” (pronounced puh-COE-sins) only exist in the Bay region in southeast Virginia. Although rare in the watershed, they occur along the Atlantic coastal plain all the way down to northern Florida. The word

pocosin comes from the Eastern Algonquian word meaning “swamp on a hill.”

Non-tidal wetlands also include small streams and waterbodies that are not continuously wet all year long, such as ephemeral streams, which only flow after rain or snow; intermittent streams, which only flow at certain times of the year; and vernal pools, which only form in winter and spring.

Why Are Wetlands Important?

Wetlands, often undervalued by humans, are among the most productive, diverse, and important ecosystems in the watershed. They improve water quality, reduce storm damage and flooding, control erosion, provide vital wildlife habitat, and help fight climate change.

Water Quality

Wetlands act as natural filters, protecting groundwater and downstream waters by trapping and treating pollutants, including phosphorus, nitrogen, and sediment. They are often referred to as the watershed’s kidneys, absorbing and cleansing polluted runoff through a complex system of physical, chemical, and biological processes before it enters the Bay.

Reducing Storm Damage and Flooding

Tidal wetlands and inland wetlands absorb the energy of storm surges and overflow due to heavy rains. By absorbing the sudden influx of water, wetlands help protect low-lying communities by reducing flooding, erosion, and property damage during major storms. Losing wetlands can exacerbate the chronic flooding that disproportionately hurts disadvantaged communities, which are more likely to be located on what was once considered marginal land.

Groundwater Recharge and Baseflow Supply to Streams

Nontidal wetlands act as a sponge and absorb water after storm events. This water retention lets water slowly percolate and recharge groundwater aquifers. During dry periods, wetlands may discharge water providing baseflow to streams, which otherwise may run dry. This balance of water flow is critical for healthy watersheds.

Erosion Control

The wide variety of plants, bushes, and trees that grow in wetlands bind the soil, preventing extensive erosion and controlling sediment. In addition, the shoots of wetlands vegetation slow down the flow of water, allowing fine sediment particles to settle, building soil elevation over time.

Wildlife Habitat

Wetlands provide some of the most productive habitat for widely diverse wildlife. Their rich vegetation provides food, shelter, spawning, and nursery areas for fish and shellfish; wintering grounds for migrating waterfowl; and shelter and food for amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds.

In the U.S., it is estimated that 90 percent of all recreational fish and shellfish harvested and 75 percent of those commercially harvested depend on wetlands for food or habitat. In the Chesapeake that includes major recreational and commercial fisheries like Atlantic menhaden, rockfish, herring, shad, and bass.

One in ten of the Chesapeake region’s endangered species rely on wetlands for survival.

Climate Change

Wetlands can store 50 times more carbon than rain forests, helping keep this climate-change contributing gas out of the atmosphere. They trap high-carbon detritus, such as leaves, animal waste, and other debris below the water’s surface. And the flooding and erosion control functions of wetlands can aid in reducing the impacts of climate change.

However, as mentioned below, wetlands are also vulnerable to climate change.

Large swathes of tidal wetlands could be lost to sea-level rise by 2100.

Thomas Henderson

What Are the Threats to Wetlands?

Unfortunately, the Chesapeake’s wetlands are threatened by development, rollbacks of federal regulations, invasive species, and the effects of climate change, including sea level rise, flooding, drought, increased heat, and more frequent and severe storms.

Development and Regulation

In 2015, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized the Clean Water Rule, which clearly defined the specific types of wetlands and waterways considered "Waters of the United States" (WOTUS) protected by the Clean Water Act. The 2015 rule, which relied on the best available science, extended the law’s jurisdiction to Delmarva Bays, pocosins, and other adjacent wetlands that significantly affect traditionally navigable waters, such as rivers and lakes, regardless of whether they have an above-ground connection to those waters.

Section 402 of the law requires anyone who wants to discharge pollutants into protected waters to obtain a permit limiting the amount of pollution that can be discharged. Section 404 requires builders, developers, and anyone else who wants to fill in wetlands or other protected waters to first obtain a permit. These permits often require development plans to be altered to avoid wetlands or require the permit-holder to restore wetlands in another location to offset the wetlands the permit allows to be filled in.

The Trump administration repealed the 2015 Clean Water Rule in 2020 and replaced it with a much narrower rule that excluded protections for Delmarva Bays, pocosins, ephemeral and intermittent waters, vernal pools, groundwater, and wetlands that cross state borders. A federal court overturned the Trump Navigable Waters Rule in 2021.

In January 2023, the Biden administration issued a new rule reinstating the pre-2015 WOTUS regulations and updating them to reflect relevant Supreme Court case law, the latest science, and the technical expertise of EPA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The rule restored protections for isolated wetlands, including Delmarva Bay and pocosions, with significant underground connection to covered waters, and to small streams that do not flow all year round.

More than half of the states, including West Virginia and Virginia, sued to stop EPA from implementing the rule. The ongoing litigation has prevented EPA from implementing the Biden WOTUS definition in 27 states. The agency has instead reverted to using wetlands regulations dating back to 1986 in those states.

The Biden administration intended to use its January 2023 definition of WOTUS later in the year as the basis for a “durable” WOTUS rule. But the Supreme Court’s May 2023 ruling in Sackett v. EPA dramatically narrowing the scope of the Clean Water Act undermined the rulemaking. It also upended decades of precedence for protecting wetlands near covered waters, wetlands science, and agency expertise implementing WOTUS regulations.

The high court held that the law covers only wetlands with “a continuous surface connection” to navigable waters. The new definition excludes wetlands that only connect to surface waters underground, such as Delmarva Bays and pocosins. Waterways that do not flow continuously all year long, like intermittent and ephemeral streams, may also be at risk of destruction.

Strong federal safeguards are essential to achieving the pollution reductions outlined in the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint. Robust federal protections are particularly important for Delaware and West Virginia, which rely on the federal definition of WOTUS to protect wetlands and streams in their jurisdiction. Maryland, New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania all have programs allowing them to regulate all or most waters within their respective jurisdictions that are not covered by the Clean Water Act.

Invasive Species

Invasive, nonnative plants and animals threaten native wetland species by crowding them out or establishing themselves more quickly or otherwise disrupting natives’ ability to thrive.

Nutria, a voracious, semi-aquatic rodent, have had a devastating impact on wetlands since their introduction to the region in the 1940s. As with most invasive species, they have no natural predators. Not only do nutria eat the roots, rhizomes, tubers, and young shoots of marsh plants, they also cause great damage to the marsh “root mat," causing erosion and other damage. They destroyed more than 7,000 acres of marshland in Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge before being eliminated from Maryland. However, Virginia’s efforts to eradicate the South American rodent continue.

Plants like purple loosestrife, Japanese stiltgrass, and especially phragmites have overrun Chesapeake wetlands, crowding out other native species and eliminating food supplies and habitat for native wildlife.

Climate Change

A number of factors caused by climate change are expected to impact wetlands. Changes in precipitation and temperature could alter habitability. In areas where development prevents tidal wetlands from shifting inland with sea level rise, they may disappear as water levels become too deep for plants. Freshwater wetlands could be affected by encroaching saltwater. All these factors affect wetlands’ critical roles for water quality, fisheries, and habitat.

Maryland’s Blackwater National Wildlife refuge, a crown jewel of the Chesapeake, could be largely underwater by 2100 due to a combination of sea-level rise and land subsidence, resulting in dramatic habitat losses. That includes a loss of more than 90 percent of its tidal fresh marsh, tidal swamp, and brackish marsh.

According to a 2021 report by researchers with the research nonprofit Climate Central, Virginia could lose 42 percent of its tidal wetlands by 2100.

Use Climate Central's interactive Coastal Risk Screening Tool to explore how sea level rise, coastal development, and maximum net vertical growth rates impact the resilience of U.S. coastal wetlands with the Coastal Wetlands in 2100 with Full Conservation map or see what changes are expected for wetlands in your county with the Percent Change in Coastal Wetlands Area by 2100 map.

What CBF Is Doing to Protect Wetlands

CBF actively opposed efforts to repeal and replace the 2015 Clean Water Rule and will continue to oppose attempts to narrow the definition of WOTUS. CBF will engage with EPA and the states as they navigate the post-Sackett regulatory landscape. CBF’s goal is to ensure that the Clean Water Act covers all non-tidal wetlands and other waters that protect the Chesapeake Bay and make the watershed unique.

In its watchdog role holding polluters and government accountable to their clean water commitments, CBF also goes to court to challenge permits that fail to sufficiently protect wetlands and adjacent waters.

And CBF engages with state water quality agencies responsible for implementing water quality certifications for federal actions that might affect wetlands. CBF is closely watching state decision makers to ensure that watershed state wetland protections are stronger than the federal protections.

How YOU Can Help Protect Wetlands

Here are five things you can do to help protect wetlands.

- Learn how your local county is addressing water runoff from parking lots and roadways.

- Encourage local projects to create and restore wetlands filter and clean water before it flows to local streams.

- Speak out against development proposals that would damage environmentally sensitive wetlands. You can join our Action Network and find other advocacy tools and resources in our Action Center.

- Educate your friends and neighbors about the importance of wetlands to protecting and restoring the Bay and its tributary creeks, streams, and rivers in your community.

- Support our efforts with a donation to help CBF continue to advocate for government policies that protect our environment.