The Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint outlines the maximum amount of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment each state in the Chesapeake Bay watershed can release into the Bay and still get our estuary off the "dirty waters" list. Find out more about what's being done. >>

Too Much Nitrogen and Phosphorus Are Bad for the Bay

Nutrients—primarily nitrogen and phosphorus—are essential for the growth of all living organisms in the Chesapeake Bay. However, excessive nitrogen and phosphorus degrade the Bay's water quality.

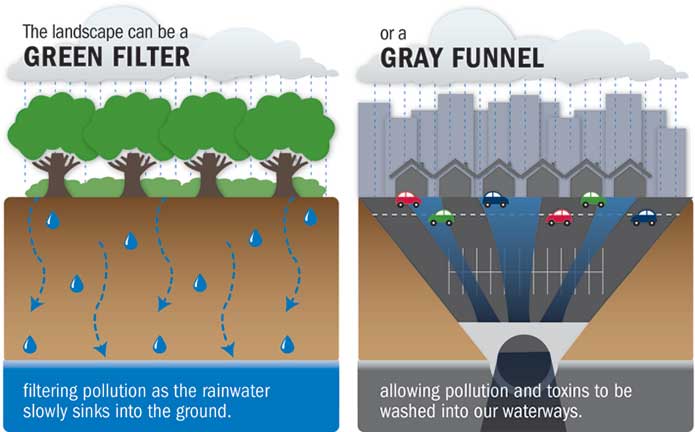

At its healthiest in the early 1600s, the Chesapeake watershed was mainly comprised of forested buffers, wetlands, and resources lands (meadows and some farmland) that absorbed and filtered nutrients. Haphazard development has stripped the watershed of these buffers, and today pollution flows undiluted into waterways. As land use patterns change and the watershed's population grows, the amount of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment entering the Bay's waters increases tremendously. Each year, roughly 300 million pounds of polluting nitrogen reaches the Chesapeake Bay—about six times the amount that reached the bay in the 1600s. CBF's health index, called the State of the Bay Report, estimates that the Chesapeake Bay watershed rated 100 on a scale of 100 in the 1600s. In 2018, the report rated the Bay at 33 out of 100. Water quality is so poor that the Chesapeake Bay is on the Environmental Protection Agency's "dirty waters" list.

Algal Blooms and Dead Zones

Both nitrogen and phosphorus feed algal blooms that block sunlight to underwater grasses and suck up life supporting oxygen when they die and decompose. These resulting "dead zones" of low or no oxygen can stress and even kill fish and shellfish. Algal blooms can also trigger spikes in pH levels, stressing fish, and create conditions that spur the growth of parasites.

Toxic algae, such as some blue-green algae (cyanobacteria), can sicken people, as well, but animals are especially susceptible. These toxins affect the animal's liver and nervous system, and can result in death. This video by the Environmental Protection Agency cautions pet owners to protect their "pooch."

Major Sources of Nitrogen and Phosphorus

The majority of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution comes from sewage treatment plants, animal feed lots, and polluted runoff from crop land, urban, and suburban areas. In addition, air pollution (from vehicle exhaust) and industrial sources such as power plants contribute roughly 1/3 of the nitrogen pollution. (see chart)

The largest source of pollution to the Bay comes from agricultural runoff, which contributes roughly 60 percent of the nitrogen and 45 percent of the phosphorus entering the Chesapeake Bay.

The fastest growing source of nitrogen pollution to the Bay is polluted runoff.

What Needs To Be Done?

Agriculture may be the biggest source of pollution, but it is also presents the biggest opportunity. Implementing conservation measures on farms is one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce pollution to our local streams, rivers, and the Bay. These practices include:

- Implementing nutrient management and conservation plans;

- Planting cover crops;

- Fencing animals out of streams;

- Installing and maintaining grassed or forested buffer strips along farm fields.

Farmers have shown a willingness to implement these practices, but they need financial and technical assistance to do so. That is why CBF has and will continue to fight at the state and federal level for conservation funding for the Bay’s farmers.

Other solutions to nitrogen and phosphorus pollution include upgrading stormwater systems and sewage treatment plants, proper operation of septic systems, using nitrogen removal technologies on septic systems, and decreasing fertilizer applications to lawns.

Because roughly one-third of nitrogen pollution comes from the air, we can reduce nutrient loads by conserving energy, which will result in fewer demands on power plants that emit nitrogen, and driving less, which reduces vehicle emissions that also contribute to airborne nitrogen loads.

Important natural filters such as forests, oysters, wetlands, and underwater grasses need to be protected and restored. Overall, the Bay has lost 98 percent of its oysters, about 80 percent of grasses, and nearly 50 percent of forest buffers.