A report from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) highlights the multiple benefits of agricultural conservation practices essential to restoring the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Farm Forward examines practices that reduce pollution, combat climate change, improve soil health and farmers’ bottom lines, and boost local economies.

Read the press release | Read the report

Conservation practices, frequently called best management practices, or BMPs, are tools that farmers can use to reduce soil and fertilizer runoff, properly manage animal waste, and protect water and air quality on their farms. These practices also reduce the amount of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere, as well as the amount of nitrogen pollution going into the Bay.

It is estimated that widespread use of these practices on Bay region farms could reduce the amount of nitrogen pollution flowing into the Bay from nonpoint sources by as much as 60 percent.

Regenerative farming practices are designed to work in harmony with nature. Successful conservation practices incorporate the top five principles of regenerative agriculture:

- Minimize the physical, biological, and chemical disturbance of the soil.

- Keep the soil covered with vegetation or natural material.

- Increase plant diversity.

- Keep living roots in the soil as much as possible.

- Integrate animals into the farm as much as possible.

Well-managed farms can be among the Bay's best friends.

Forest buffers separate farm fields from the West Branch Susquehanna River, providing a highly effective filter that reduces the amount of nutrient and sediment pollution that runs into the Commonwealth's waters.

Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program

1. Streamside Forest Buffers

Forested buffers, also called riparian buffers, are areas bordering stream banks that are taken out of crop production or pasture use and planted with native trees, shrubs, or grasses. Buffers are at least 35 feet wide on either side of a stream. They act as natural filters that slow water flowing off the surrounding fields and allow nutrients from fertilizer and manure to soak into the ground. They benefit both the farm and the streams by reducing erosion of soil, and farmers can select trees that provide additional benefits—such as shade for livestock or fruit and nuts that can be harvested as additional crops.

Trees remove carbon dioxide directly from the air through photosynthesis. They move carbon into the soil, as well as store it in their leaves and branches, keeping it out of the atmosphere where it contributes to climate change. Each acre of forest buffer removes approximately 0.91 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year.

Buffers also cool the surrounding land and waters, a valuable function as temperatures rise and extreme heat events become more common, and provide refuge for wildlife and pollinators.

If the Bay states meet their commitment of implementing 190,500 acres of forest buffers by 2025, it would remove more than 173,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually—equivalent to the annual emissions of more than 37,600 passenger vehicles.

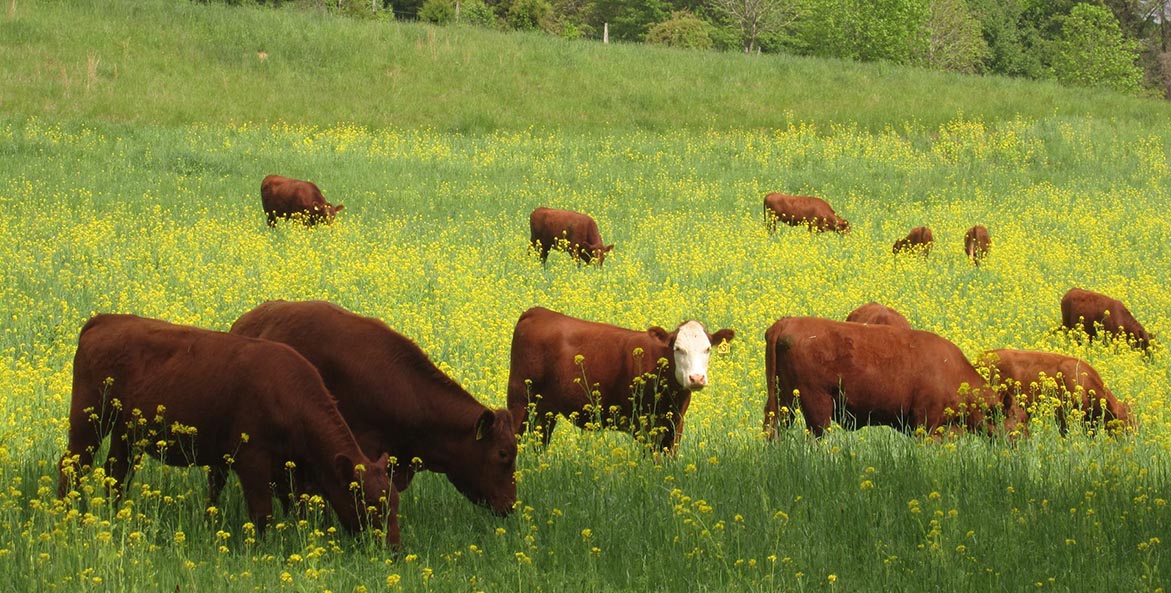

Rotationally grazing livestock on grass pastures enhances soil health, protects and improves water quality, and contributes to a farm's economic viability.

Deborah Starobin Armstrong

2. Converting Cropland to Pasture and Rotational Grazing

Livestock operations often grow corn and other crops to feed their animals. By converting this land to pasture, farmers can build their soil health and create a permanent cover of vegetation that traps soil, water, nutrients, and carbon. In addition, rotational grazing involves frequently moving livestock between small grass pastures, sometimes as often as once a day, rather than keeping livestock on the same area of land for long periods of time. This allows plants time to regenerate, preventing bare ground and keeping pastures more vibrant with healthier soil. By moving animals frequently, rotational grazing also spreads manure naturally over the land rather than concentrating it in one place.

CBF’s multi-year study of farms in the Bay watershed that converted conventional farmland to rotationally grazed pasture found an average reduction of 42 percent for net greenhouse gas emissions along with average pollution reductions of 63 percent, 67 percent, and 47 percent for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, respectively.

For information on how to manage regenerative grazing, see our brochure Stepping Up Your Grazing Management.

3. Continuous No-Till

Continuous no-till, also known as conservation tillage, reduces erosion and runoff by minimizing soil disturbances. Traditional plowing and tilling creates deep furrows in the ground and turns soil over, leaving it unprotected and vulnerable to erosion by wind and water. By minimizing tillage, farmers can build their soil’s health and encourage beneficial microbial life. Healthier soils have a greater capacity to filter water and retain moisture, reducing runoff and keeping nutrients in the ground. Healthy, undisturbed soil can also store large amounts of carbon, keeping it out of the atmosphere and benefiting the climate.

4. Conservation Crop Rotation

Conservation crop rotation is rotating the types of crops grown on a piece of land in a planned sequence. Crops may alternate, for example, between those with deep roots and shallow roots or those that depend on or fix certain nutrients. Growing the same crop on the same land constantly gradually depletes nutrients in the soil. A well planned crop rotation can reduce reliance on one set of nutrients, reduce pests and weeds, reduce the need for fertilizer, and improve soil structure and organic matter, which increases farm resilience and decreases soil erosion and flooding.

Rye grows at the The Bishop Claggett Center in Buckeystown, Maryland. Grains such as rye or wheat are useful winter cover crops that hold soil in place, protecting land from erosion by water and wind.

Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program

5. Cover Crops

Cover crops are not sold, but provide other benefits to the farm, such as soil improvement, water retention, weed suppression, and erosion prevention. They are typically grown at strategic times before or after cash crops, such as corn or soybeans, to ensure farm fields are continuously covered in vegetation. This both protects bare soil from erosion and makes sure any excess fertilizer in the field is held in plants, rather than washing off into waterways. Cover crops can also enhance the health of the soil. For example, certain crops add back nutrients that were depleted during the main harvest, while others help break up the soil with their roots—providing natural tillage without disturbing the soil overall.

A dairy herd is surrounded by tall, white, tree shelters in a young silvopasture. When the trees are grown, the herd benefits from the shade and forage provided. Herd health is improved and the dairy farmer can save on feed costs.

BJ Small/CBF Staff

6. Silvopasture

Silvopasture—intentionally planting trees on grazing land—can enhance herd health by offering shade, shelter, better quality grazing, and reduced stress on livestock. Mature trees also reduce polluted runoff, sequester carbon, and contribute to healthier soils.

7. Nutrient Management

Nutrient Management Plans (NMPs) are documents that outline how much and when fertilizers should be used on a farm’s crops. This helps ensure that crops are able to use the fertilizer when it is applied, reducing nutrient runoff into local waterways and minimizing farmers’ fertilizer costs.

8. Streamside Fencing

Installing fences along streams in pasture areas is a simple but essential way to reduce pollution on farms. Fences keep livestock and their waste out of waterways, reducing pollution and erosion and helping prevent the spread of waterborne disease. Water pumps and lines, and even solar-powered mobile watering stations, can provide viable alternative water sources for the animals. In addition, the purchase of necessary supplies and labor benefits local businesses. While streamside fences do not affect greenhouse gas emissions, they are often used together with other practices that do—such as streamside forest buffers and grazing systems.

Farm Conservation Practices Build Climate Resiliency

Most of the practices above result in more resilient farms. When soil health is improved it is better able to filter and retain water. Because healthy soils retain water better it both takes them longer to dry out during droughts and improves their capacity to absorb rain water during heavy storms. Healthy soil also means crops may be less vulnerable to pests, diseases, and other climate-related risks. Forested streamside buffers have a cooling effect on nearby land and streams—an increasingly important role as water temperatures rise and threaten aquatic species, like trout, that need cool water to survive.