Oysters are a keystone species in the Chesapeake Bay—integral to good water quality, fish habitat, and the seafood industry. While populations remain at a fraction of their historic extent, large-scale reef restoration projects are showing promising results and are seen as a true bright spot in the Bay cleanup effort. To understand how oysters may fare in the Bay in the year 2100—and what that means for life here—I spoke with CBF’s Maryland Coastal Resource Scientist Julie Luecke, who has taken part in large-scale restoration projects in both Maryland and Virginia. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: This discussion started by asking AI what life might be like in the Bay in 2100, and part of that was what a future with oysters could look like. Some of the things Microsoft CoPilot imagined included oyster cities and parks, floating oyster farms, and oyster-powered water purification systems. What was your overall take on its responses?

A: I would say it was more right than it was wrong, in general. Since you brought up oyster cities, I’ll start there. It talked about integrating oyster reefs as natural breakwaters to protect against storm surges and erosion. That is actually our trajectory right now. In Virginia, oyster reefs can be intertidal, so they can be used as part of a living shoreline. That’s already happening.

In Maryland, we’re trying to figure out how they work as breakwaters since they don’t do as well intertidally here. I think by 2100 we should have pretty good science to tell us how you can build these in a way that we’re fairly confident will reduce erosion and reduce wave energy. And oyster reefs grow over time, so as sea levels rise, theoretically those reefs should grow at more or less the same rate.

Q: So, no underwater oyster parks, though?

A: I love the idea of reefs serving as underwater parks! Maybe by 2100 we can get clear enough water, but that has so much to do with the biota that live in the water, more so than how clean it is. So, in the Chesapeake, I wouldn’t anticipate we’ll get sparkly Florida-like water. And it’d be different than coral reefs, where the more color you have [as a fish] the more you blend in. In the Chesapeake Bay, the less color you have, the more you blend in.

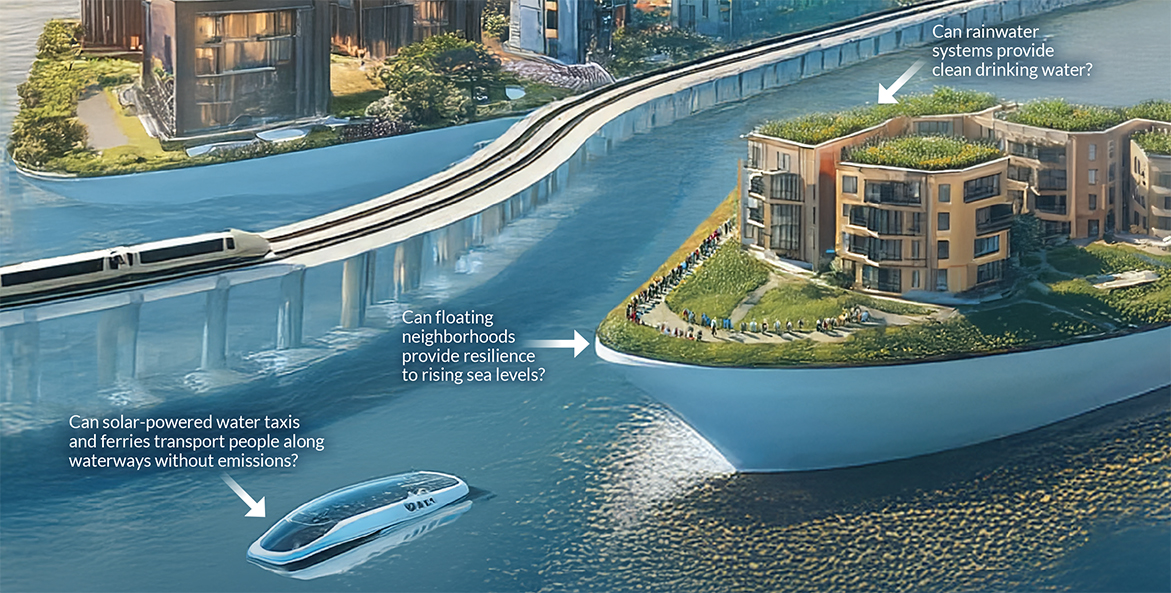

Q: What about oyster farms being integrated into floating neighborhoods in these futuristic communities?

A: I think that’s the most important one AI hit on here. Floating neighborhoods I’m not so sure about, but oyster farming is definitely the future of oyster production. I feel like sometimes “aquaculture” gets a bad rap since many people associate it with fish farming. But with oysters, even though you’re farming them to take out of the water, while they are in the water they’re still filtering that water. They are still providing habitat, and they’re ultimately reducing the harvest pressure on wild oysters.

Q: AI also thinks that the future of oyster cuisine could really take off. Do you see people eating more oysters in the future, especially since they and other bivalves have been floated as a way to produce more protein with fewer climate and environmental impacts?

A: I think there are a lot of people who want that. And I think there are probably a lot of people who are like, ‘I’m not eating oysters every day.’ Some people want oysters at McDonald’s; I love oysters, but I don’t know that I’m there.

But I do think the thought is that farming can scale in a way that doesn’t detrimentally impact the wild population. We’re almost in between the hunter-gatherer phase and the big animal operation phase. So, I think part of it is figuring out how we make sure this industry doesn’t become a monstrosity the way that factory farming has—and maybe it never would get there anyway because so many oyster growers are already so entrenched in sustainability and committed to that route.

Q: Are there conditions—thinking about climate change and changing habitat—that might be present in 2100 that you worry might influence oysters and the future we ultimately see?

A: For sure. The biggest thing that a lot of this depends on is, will our government decide to stop using fossil fuels? There are so many trajectories, but as it’s trending right now, I think ocean acidification is one of the biggest issues because oysters build their shells directly in response to the environment they’re in.

Oyster shells are made out of calcium carbonate. The more acidic the ocean, Bay, and rivers are getting, the harder oysters have to work at building and maintaining that shell. As an organism, the more energy you put into anything, the less you’re spending on things like reproduction.

With warming waters also come more algae blooms. Oysters have this preventative role [in filtering water] but once the bloom is there, they are not able to move. They can hang out and ‘clam up’ for a little bit, but those [blooms and dead zones] do cause mortality.

Q: You say there could be a flipside to that, though, too.

A: As the air and waters warm, the intertidal oyster range will likely increase—so we may see intertidal oysters in Maryland by 2100. The longer warm period in the summer also means a longer reproduction period.

Oysters reproduce in the Chesapeake Bay roughly from the end of May until the end of September, depending on the temperature and salinity and where you are. In Maryland, you kind of see two pulses, one in late June or early July and another in mid-to-late August. In Virginia, we’re starting to see three. We’re getting early to mid-June, late-July or early August, and the end of September because the water is staying warmer.

It’s still so new and anecdotal that no one’s been able to really study what it means for the oyster population, but theoretically it could improve their rates of reproduction.

Q: What do you think all this means for restoration and the future of oysters writ large?

A: I think one of the biggest hurdles right now—but I feel good about us getting over it—is the marriage of oyster harvesting and oyster restoration. And aquaculture is a huge part of it.

Right now, restoration programs primarily plant oysters on sanctuary sites, meaning they cannot be harvested. And I think that hard line between sanctuary and harvestable has made sense. But I think it will become a more symbiotic relationship, where we’re taking farmed oysters out of the water to enjoy and putting all of the shell back on the bottom so that the wild population can reproduce. It will be a self-reinforcing cycle.

I think we’ll see some of the large-scale restoration back off. Maybe in the next 35 years we’ll have put all the oysters in the water that we can, and it will hopefully be more of a maintenance thing in 2100. So yes, we will still be doing restoration, but I think it will look a lot different and become more integrated into eating and enjoying oysters.

Check out our article "The Chesapeake in 2100" in the Winter issue of Save the Bay magazine.