This is the first in a series of stories about the great clean water work that is happening upriver in West Virginia, Delaware, and other states that don’t directly border the Bay. Much of the funding and resources for this critical work are only made possible through the landmark 40-year Bay partnership, a collaborative effort between states, the federal government, and local partners to reduce pollution and restore habitats across our remarkable watershed.

Up in the mountains where West Virginia’s Lost River begins, the water trickling though Wilding Woolly Farm is virtually pristine. Owners Hope and Bev Yankey are committed to keeping it that way so native brook trout might one day thrive downstream.

They’re equally passionate about letting land that had once been farmed intensively return to a more natural state. Hope even changed the name from “Wild ‘n’ Woolly Farm” to “Wilding Woolly Farm” to emphasize their effort to “re-wild” parts of it.

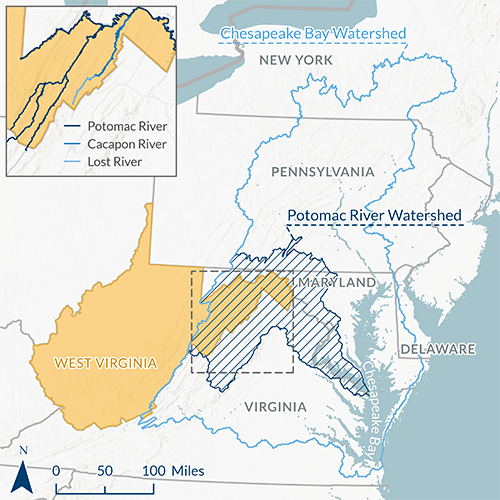

So the conservation-minded couple turned to Trout Unlimited (TU) and its Potomac Headwaters Home Rivers Initiative for help. The Lost River, and the Cacapon River, which the Lost River becomes after getting “lost” underground, are among the headwaters of the Potomac River.

West Virginia's Potomac River Watershed, part of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, includes the Potomac, Cacapon, and Lost Rivers.

Chesapeake Bay Foundation

Protecting West Virginia's Native Brook Trout

Protecting the Potomac headwaters and surrounding land is essential to bolstering populations of West Virginia’s beloved native trout species. Brook trout need cold, clean water to survive. And that’s exactly how it emerges from the limestone underlying the state’s mountains and aquifers.

Safeguarding the headwaters also helps improve water quality downstream all the way to the Chesapeake Bay. The Potomac is the Bay’s second largest tributary and an important source of fresh water.

Brook trout’s sensitivity to water temperature and conditions make them an excellent indicator of stream health. That’s why the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement made restoring brook trout a goal of the federal-state effort to clean up the Bay and its tributaries. Other goals include conserving working forests and farmland; reducing pollution from nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment; and increasing resiliency to climate change and its effects.

Grant Programs and Partnerships Make a Difference

The work can be expensive and complicated. Fortunately, an array of federal and state grant programs exists to help cover the costs and provide technical expertise to landowners, like the Yankeys, who want to protect valuable natural resources on their property.

A grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program, which coordinates the cleanup, paid for some of TU’s work on Wilding Woolly Farm. The grant was awarded to the Cacapon and Lost Rivers Land Trust, which contracted with TU to do restoration work, coordinate with the Yankeys, and provide technical assistance on parts of the project.

The goal is “to regenerate and let the land come back. The farm provided a living and now it’s time to give back.”

Funding also came from the Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP). CREP is a Farm Bill cost-share program that helps defray farmers’ costs for installing conservation practices, such as fencing livestock out of streams and planting forested buffers along streams. CREP also provides technical assistance through USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.

CBF has long advocated for robust federal funding for the Chesapeake Bay Program, CREP, and other Farm Bill conservation programs.

Another source of funds was the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program. The program offers financial and technical help available to private landowners, like the Yankeys, who want to improve wildlife habitat on their land. On Wilding Woolly Farm, they’re protecting wood turtle habitat.

The Yankeys partnered with TU about a year and a half ago to install roughly 4,500 feet of fence on their farm. The fencing allowed them to set aside the best pastureland for their Highland cattle and sheep to graze—and keep the animals off the 23 acres where they planted 1,096 native tree seedlings in two days.

TU also installed a trough that draws from one of the property’s wells, giving their livestock another source of water now that the stream is off-limits. Bev lent a hand by prepping the well system for TU to tap into.

Protecting the Integrity of Our Water Resources

“This had been farmed long ago, even before we were here,” Hope said. “They actually planted corn in these back fields all the way to the top of the mountain. The ground, being shale, was pretty well destroyed.”

The goal is “to regenerate and let the land come back. The farm provided a living and now it’s time to give back,” Hope said. The fence and growing trees aren’t just helping recreate a forest where corn once grew. They also keep the livestock away from the tiny stream making its way down onto the farm from Bald Knob. And they protect the stream banks from erosion and keep sediment and manure out of water that hasn’t traveled far from its source.

“All of this water is the extreme beginning of the Lost River,” Hope said. "This is very clean water. This is an incredible resource. It’s not about just protecting us. It’s about saying this is an incredible resource, and I would like to see this whole area protected.”

Starting at the top of the Potomac watershed and working downstream is one reason why West Virginia is leading the other five watershed states in meeting its Watershed Agreement goals for reducing nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, said Dustin Wichterman.

According to the latest modeled data, the state has already achieved 100 percent of its nitrogen and sediment reduction goals ahead of the 2025 deadline, and 91 percent of its sediment reduction goal. EPA modeling shows West Virginia is on track to meet 100 percent of its sediment reduction goal by the 2025 deadline.

Wichterman oversaw the work on Hope and Bev’s farm as part of his job as Associate Director of TU’s Mid Atlantic Coldwater Habitat Program, Eastern Region.

“We have incredible water quality as it leaves these mountains,” Wichterman said, pointing to a hollow between the mountains in the Lost River Valley, between Petersburg and Moorefield, West Virginia. "There’s a limestone spring that comes out right there and it’s loaded with brook trout.

“So long as we’re able to protect that integrity from its sources, as well as when it goes downstream, we’re in good shape,” he said.

And so are the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay.

Washington, D.C. Communications & Media Relations Manager, CBF

[email protected]

202-793-4485

Issues in this Post

Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint Agriculture Conservation Restoration