UPDATE: Since publication of this blog, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission voted to establish a workgroup to consider additional protections from industrial fishing of menhaden in the Chesapeake Bay after hearing new survey results that show low osprey nesting success in the Bay at the August 6 meeting.

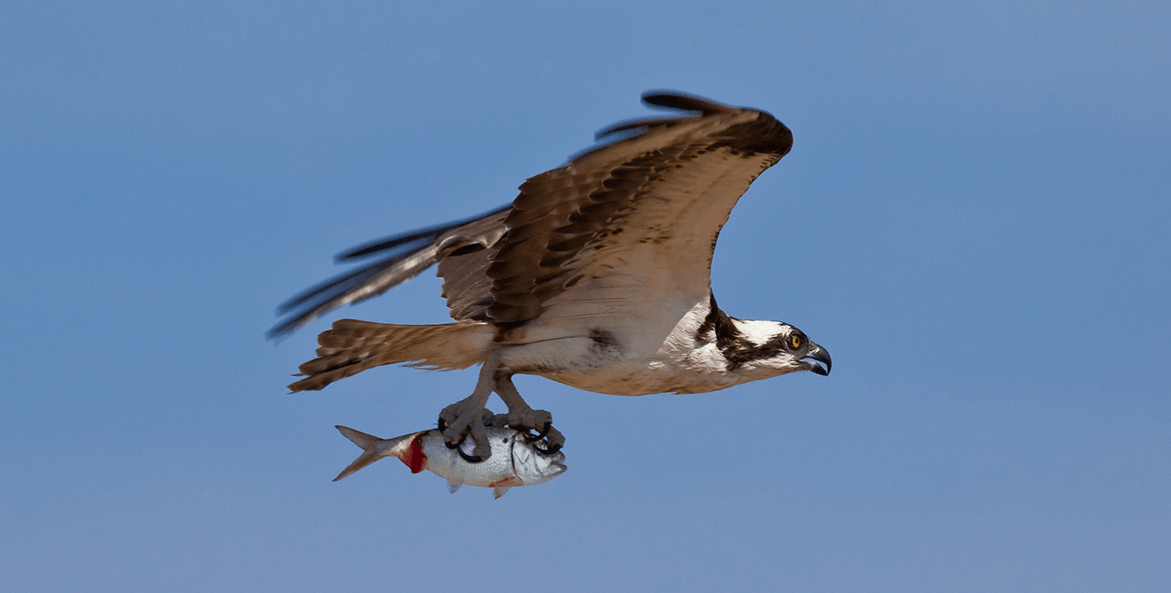

In the 1960s and ’70s, osprey almost entirely disappeared from the Bay region. The reason? DDT, or the harmful insecticide that wreaked havoc on birds and other wildlife before Rachel Carson’s heroic Silent Spring spurred a ban on the deadly pesticide. After the ban, the Bay’s osprey population rebounded from roughly 1,450 breeding pairs to more than 10,000. But now, in one portion of the Bay, osprey have dropped to even lower levels than the DDT era. A suspected culprit? The lack of menhaden—a foundational fish that is critical food to a number of important species, including osprey.

“It was a catastrophic failure,” said Bryan Watts, director of William & Mary’s Center for Conservation Biology in Virginia, describing what he saw last summer when studying the osprey nests in Mobjack Bay—a beautiful stretch of water nestled between the York and Rappahannock Rivers. Watts, who has been studying local ospreys for decades, noticed that out of 167 nests he and researcher Michael Academia visited in Mobjack Bay and two nearby rivers last summer, only 17 held live chicks. In fact, the osprey reproductive rate in this part of the Bay had dropped to 0.47 young per active nest–compare that to 0.7 in 1970, according to the USGS. A reproductive rate of 1.15 young per nest per year is needed to sustain the osprey population.

The Osprey-Menhaden Connection

Menhaden are small, oily, and highly nutritious fish. Often called “the most important fish in the sea,” they are a critical link in the Chesapeake Bay food web, feeding striped bass, bluefish, ospreys, whales, and more. In fact, some studies show menhaden make up roughly 75 percent of an osprey’s diet.

But the same qualities that make menhaden a prized food for marine wildlife, have also long made them a target for the reduction industry—or a type of fishing that involves catching and processing wild fish and grinding them down into fishmeal and fish oil for use in other industries. Since colonial times, menhaden have supported one of the largest commercial fisheries along the Atlantic coast. Used for cosmetics, nutritional supplements, pet food, and other consumer products, the menhaden “reduction” fishery is responsible for the harvest of hundreds of thousands of metric tons of menhaden each year.

Today, reduction fishing pressure comes from one company—Omega Protein, a subsidiary of international salmon farming conglomerate Cooke, Inc. And while this fishery has been around for centuries with reduction plants at one point dotting the East Coast, Virginia is the only state that continues to allow reduction fishing in its state waters, accounting for nearly 75 percent of all the commercial menhaden harvest coastwide. And though advances in fishery management have improved our understanding of menhaden as a coastwide stock, much remains unknown about the impacts of this industrialized harvest within the Bay.

“It is more important than ever to quantify localized depletion of menhaden in the Chesapeake,” says CBF’s Virginia Executive Director Chris Moore. “Without this information, species like osprey will continue to bear the weight of Omega’s fishing activities while the company continues to profit.”

A Bay Without Osprey?

Often called “the osprey garden,” the Chesapeake Bay is home to the world’s largest breeding population of ospreys. “They’re an iconic bird,” says Remy Moncrieffe, marine conservation policy manager for National Audubon Society. “They’re one of the most approachable birds in the world. They’re historically everywhere. And they are a great indicator species.” With their distinctive cheep cheep cheep, majestic dives, and admirable work ethic, osprey—a tell-tale sign of summer on the Bay—are extraordinary birds. They mate for life and each spring return (often traveling thousands of miles from Cuba, Colombia, and other points south) to nest in the same area where they were born.

“Osprey are a very resilient species,” says Moncrieffe. “To see them decline like that [in Mobjack Bay], means that they’re not getting a chance to recover.”

Ospreys are the species we see. Their decline could mean catastrophe for so many other things we don’t see.

And osprey are not the only birds that rely on menhaden. Other Chesapeake birds like bald eagles, loons, and brown pelicans eat menhaden. And farther north, puffins, herons, even arctic terns (remarkable birds that cover roughly 25,000 miles each year, flying from the Arctic to Antarctica), eat this important, fatty fish. If not enough menhaden are able to make their way out of the Chesapeake Bay (where they spawn) to travel north up the coast, that could mean drastic impacts to these other birds and other species. “What we do in Virginia sets the tone for the rest of the Atlantic,” says Moncrieffe. “This isn’t just a Virginia problem . . . this is a problem that reverberates all up and down the coastline.”

“The health of the osprey,” continues Moncrieffe, “is directly tied to the health of the Chesapeake Bay. If you see a problem with the osprey, there’s a problem with the Bay. Ospreys are the species we see. Their decline could mean catastrophe for so many other things we don’t see.”

What’s Next?

The effects of the Chesapeake Bay menhaden fishery on osprey sparked discussion at the most recent Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s (ASMFC) Atlantic Menhaden Management Board meeting in April. As a result, the ASMFC’s upcoming August meeting is expected to include a presentation on the latest data on osprey abundance, nesting success, and when and where osprey spend time and nest in the Chesapeake Bay.

“Menhaden play a key role in the Bay’s food chain,” says CBF’s Maryland Executive Director Allison Colden (who also sits on the ASMFC’s Menhaden Management Board). “But there is a critical data gap in understanding the needs of predators in the Chesapeake Bay. By considering impacts to other species of concern like osprey, the ASMFC is on a path toward more holistic management of the menhaden fishery.” Stay tuned for updates on this critical issue later this summer.

For more than 25 years, CBF has been working tirelessly to protect menhaden, and many of our successes have been thanks to vocal advocates. Join the movement and sign the pledge to save our menhaden! Commit to doing your part to restore this all-important Bay species. The Bay, our economy, and our way of life depend on it.