On the Eastern Shore of Maryland, the Transquaking River is impaired. Before it flows past Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge and empties into Fishing Bay, it carves through miles of the Shore’s flat coastal plain.

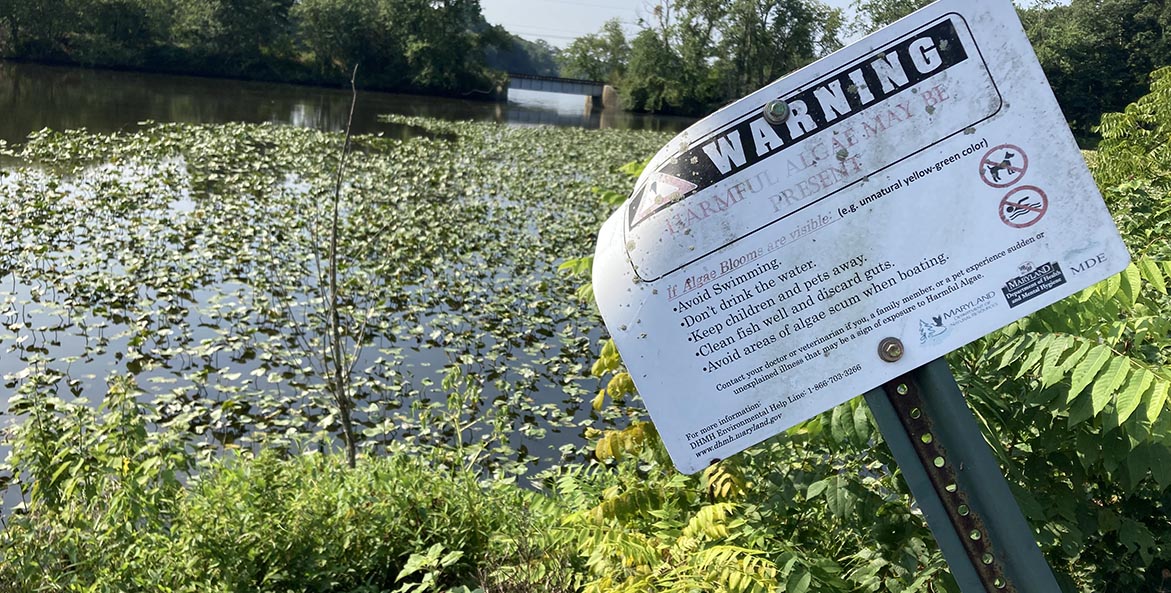

A hint of its troubles is visible in late July at Higgins Millpond, a long impoundment of the river south of Cambridge. Traces of electric bluegreen algae sweep across its surface like cloud wisps. The toxin-producing blooms are responsible for permanent signs warning people not to swim.

Just upstream of the millpond is the Valley Proteins poultry rendering plant. Clean Water Act permits are meant to regulate industrial wastewater pollution from facilities like this, but the plant has a long history of violations. In early 2022, CBF, ShoreRivers, and Dorchester Citizens for Planned Growth joined a state-filed lawsuit over the plant’s failure to comply. A settlement in that case resulted in $540,000 in civil penalties paid to the state.

Now, under new ownership, the plant is seeking to expand. Its discharge permit—which allows it to release wastewater into the river just above Higgins Millpond—was issued in 2001 and “administratively continued” by the state for 17 years. A renewal of that permit that was finalized in 2023 would allow it to discharge up to 575,000 gallons per day, more than three times the amount it has been discharging in the past.

It accommodates the plant’s processing of 20 million pounds of poultry offal from Delmarva’s slaughterhouses each week, more than double the amount of material processed in the 1990s. “We’re challenging the permit because the limits are not strong enough to address water-quality problems in the Transquaking system,” says Ariel Solaski, CBF’s Litigation Staff Attorney.

Industrial wastewater discharge is just one challenge posed by the intensification of livestock production in places like the Delmarva Peninsula, one of the largest poultry producing regions in the country. Intensification concentrates so many nutrients in certain areas of the watershed that conservation practices can’t keep up—a problem the CESR report calls a “mass imbalance.”

“The size of the birds has increased, the amount of meat has increased, the tons of manure generated has increased,” says Alan Girard, CBF’s Eastern Shore Director. “We have increasing loads from that industry that need to be accounted for and aren’t.”

One example is the byproduct of Valley Proteins’ wastewater treatment process called “DAF,” the sludge of fats and solids left over after the offal boils down. Wastewater is regulated by the plant’s permit, but the DAF, hauled away in trucks by third-party contractors, is not.

The nutrient-rich material may be applied directly to fields as fertilizer. Or, it may be stored in large holding tanks—one of which spilled into wetlands in Wicomico County last March. It’s hard to know the final destination. The Maryland Department of Agriculture’s nutrient management program requires farmers to create plans for applying manure and fertilizers so as not to exceed what crops can use—at least on paper, says Girard. But the plans aren’t publicly accessible.

“There is no verification for the public to see if it’s working or not, to see if the farm is actually aligned with its plan,” Girard says. “The nutrient management plan program is a black box.”

Public availability of the plans—at least for farms that receive industrial waste like DAF—could ensure more accountability for Clean Water Act permittees like Valley Proteins and help states address mass imbalance issues. In the meantime, Solaski says CBF and its partners aim to ensure any new permit for the plant results in real reductions in pollution to Higgins Millpond and the Transquaking River.

Take a look at our fall Save the Bay magazine for more stories like this.