If you live in the northern regions of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, you’ve likely noticed unusually hazy skies obscuring the sun this week. You may also be one of the 55 million Americans under advisories for unhealthy air quality, which prompted officials to warn residents of Philadelphia to stay inside and canceled outdoor activities at schools in Washington, D.C. Wednesday, CNN reported.

The cause is massive wildfires raging hundreds of miles away in northeastern Canada, which have burned more than 600 square miles in Quebec so far this year. It’s a visceral reminder of just how far air pollution can reach, and the very real impacts to human and environmental health here in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

“Air pollution doesn’t respect boundaries,” says CBF Litigation Staff Attorney Ariel Solaski, who works on air pollution issues in the watershed. “It’s concerning when something like this happens and we see communities affected by unhealthy air. It’s also a stark reminder of the harmful effects of air pollution, even when we can’t see it, especially in communities overburdened by sources of air pollution —and it’s not just impacting us as people, but also the health of our rivers, streams, and the Bay.”

At CBF's Philip Merrill Environmental Center in Annapolis, haze begins to obscure trees just across the narrow neck of Black Walnut Creek. Photo taken June 8, 2023.

Emmy Nicklin/CBF Staff

Air pollution is the source of as much as one-third of the nitrogen pollution that enters the Bay, as pollutants dispersed in the air fall back to earth or are washed out of the air by rain in a process called deposition. Excessive nitrogen in turn drives large algal blooms that create oxygen-depleted dead zones in the water when they die and decompose.

Usually, this pollution comes from power plants, industrial sources, and vehicle exhaust. Researchers, however, have found that wildfires can contribute significant amounts of nitrogen pollution to the air, affecting waterways and forests over large areas downwind. In California, wildfires increased nitrogen deposition an estimated 78 percent in 2020. This is particularly concerning because failure to reduce greenhouse gases threatens to lock us into a future where wildfires like we're seeing now become increasingly common. A report released last year by the UN Environment Programme estimated extreme fires globally could increase 15 percent by 2030, 30 percent by 2050, and 50 percent by 2100 due to climate change and land use change.

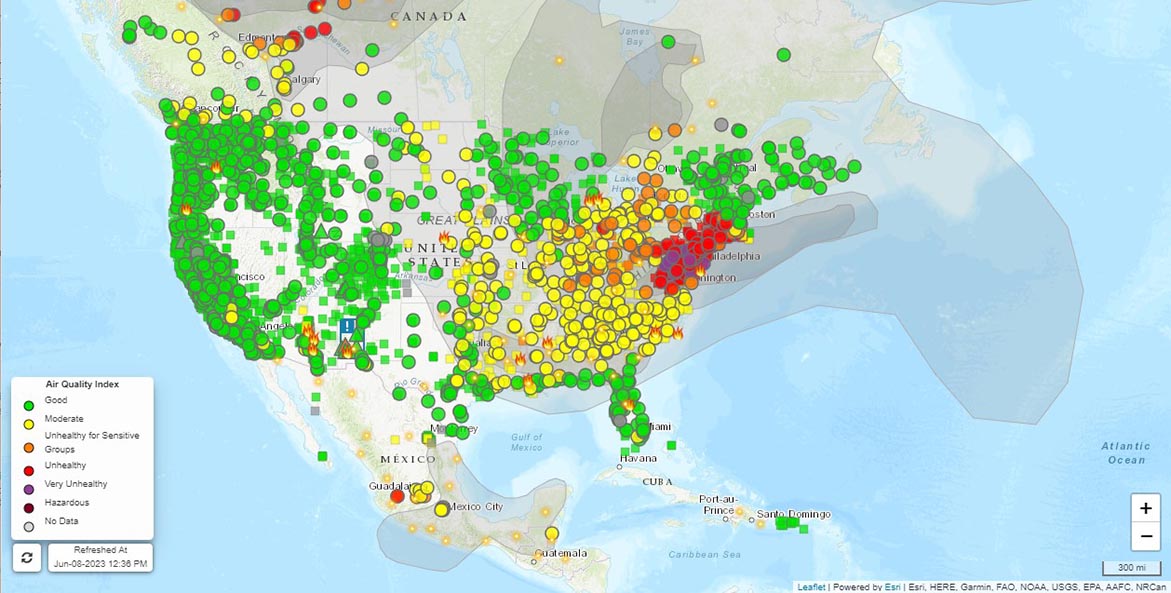

This Fire and Smoke map from AirNow, showing data from June 8, 2023, shows New York to Virginia as having unhealthy to very unhealthy air quality conditions from fine particulate matter generated by various sources, including wildfire smoke.

AirNow fire.airnow.gov

It's less clear what, if any, impact the current fires may have on the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The area from which the Chesapeake region’s air travels—called the “airshed”—is more than nine times the size of the watershed itself, meaning pollution can arrive from as far away as Canada in the north and Indiana and Kentucky in the west. Quebec isn’t normally included in the Bay’s airshed, but a storm off Nova Scotia brought the smoke further south than usual.

“Normally, smoke from wildfires that far away, if they affect the Bay watershed at all it would be for a short period of time. But this blocking high weather pattern that is prolonging the drought conditions in the northeastern U.S. is bringing days of smoke over the same areas, allowing dry deposition of the nitrates,” says CBF Maryland Senior Scientist Doug Myers. “Our friends in the Adirondacks are reporting it's very thick up there. That means much of the upper watershed is receiving dry deposition nitrates not normally part of the airshed, and when it does start to rain, there could be an increased load to the Bay.”

While distant wildfires may be largely out of our control, reducing sources of air pollution that we do have control over—such as emissions from power plants and vehicles—remains a critical part of protecting the health of the watershed and Bay communities. For example, CBF joined the Southern Environmental Law Center, Sierra Club, and the Chesapeake Climate Action Network in filing comments this week on a proposed gas pipeline and compressor station project that poses environmental justice and pollution concerns in Virginia. CBF also continues to closely monitor the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Good Neighbor Plan, which aims to reduce the amount of air pollution that crosses state boundaries. The agency published the final plan in the Federal Register this week.