On a blue-skied December Tuesday after Christmas, a family gathers. Cousins, uncles, mothers, fathers, grandsons come together on the land their family has called home for generations. In fact, the Wilson Family has been tied to this land that juts out into the wide open Yeocomico River before curving into the Potomac since 1877–a rare thing for a Black family in the south.

“What a remarkable family legacy of life on the water,” says Otis Jones, CBF Board Chair and family friend. “‘The Point,’ as the Wilson Family calls it, is a special place steeped in the history of one family’s successful nurturing of mother nature’s watershed treasure.”

Today, in Brooke and Byron McKie’s light-filled living room overlooking the Yeocomico, the family reminisces. All together there is Brooke and Byron McKie and their son Grayson, Wayne Wilson, William and Yvonne Wilson, James and Daisy Douglas, James (or Jimmy) Wilson, George (or Kip) Wilson and his son Joseph, Cecil and Ervina Johnson, Darlene Wilson Thomas and Joyce Johnson (who join on Zoom). They talk with a hearty warmness about their family and this land and water that has meant so much to them for 146 years. This is their story.

A Dreamer's Dream

Mitchell Wilson (or Mitchell I as he was later known within the family) was a “dreamer” says Daisy Douglas. As the story goes, Mitchell I was a sailor working on a schooner hauling lime or lumber on the Potomac River in the 1870s. As he sailed out of Kinsale Harbor, he spotted the peninsula just below Sandy Point that his descendants would soon call home.

That moment in time in Virginia, particularly on the Northern Neck—the peninsula nestled between the Potomac and the Rappahannock Rivers—was brimming with excitement. As William Byrd wrote in 1732, “In the beginning, all America was Virginia.” Nowhere was that more true than on the Northern Neck. A region deeply tied to the bountiful waters that surrounded it, the Northern Neck bustled with farming, fisheries, and eventually steamboat activity throughout the 1800s. It also birthed more U.S. Presidents than any other place in the country.

Westmoreland County, where the Wilson Family put down roots, had the highest percentage of Free Blacks than any other county on the Northern Neck. Still, Mitchell I was met with steep obstacles when he tried to purchase the land he spotted from the water that day in the late 1870s. In order to purchase the land, a white family friend Thomas Brown first bought the property and then immediately sold it to Mitchell I and his two sons, Mitchell II and David. So important was it to keep this land within the family, that it was even written within the deed that the property could only be sold to other members of the Wilson Family in perpetuity.

Ariel view of the Wilson property along the Yeocomico River near Kinsale, Virginia on the Northern Neck.

James Smith

“[They] saw what we couldn’t see,” says Kip Wilson of the foresight that Mitchell I and his sons and grandsons had into the importance of keeping this land within the family. Now, eight generations later, the beautiful 12 acres that overlook the Yeocomico remain in Wilson Family hands. And of the more than 14 family members who gather together that day in late December, four live there full-time; the rest visit frequently.

“When I come here now [to visit],” says Wayne. “I stand by the water and say, ‘Thank God we didn’t give this up.’ Water, family, this is a piece of Heaven. I think of the song, Heaven Must Be like This.

"Once That Water Gets in Your Veins, That's It"

No doubt the Wilson family’s connection to the water is deep. Many members were and some continue to be watermen, working the menhaden fishery or oystering and crabbing. They learned the winds and tides, and they learned how to run boats at an early age from the generation before them. Many never wanted anything else; others felt the pull of the water and their home later in life.

For William Wilson, who started crabbing as a boy with his father, Leslie Wilson, Sr., he wanted nothing to do with being a waterman—he wanted to see what else was out there. “But as I got older, I always knew I was going to come back home. I came back and started crabbing . . . I still have my father’s crab and oyster licenses, which you can’t purchase anymore.” Now William says, “I think the water’s the most beautiful thing in the world. I used to go out every morning and say ‘heavenly father, this has got to be heaven. Anything that looks this good’s got to be heaven.’ I always knew I would come back. My foundation came from here.”

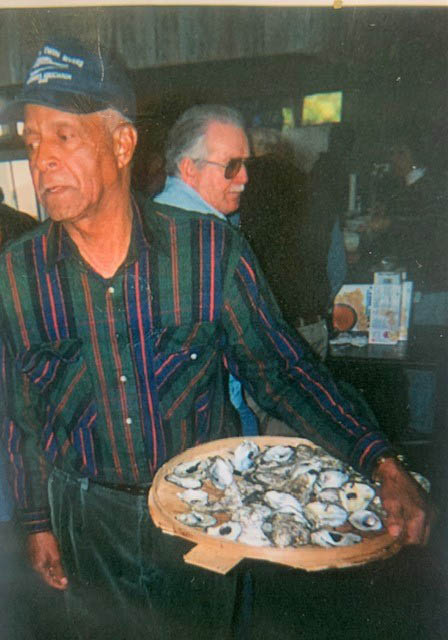

A waterman, family man, churchman, athlete, Leslie Wilson, Sr. was an esteemed member of the community, always at the ready to help anyone and everyone in need. Here he holds a plate of oysters while working at an annual oyster festival.

William Wilson.

Kip, who continues to work in the menhaden industry, never wanted anything else. “I’m a fourth-generation fishermen, grew up crabbing, oystering, eeling. Whatever my grandfather [Leslie Sr.] did, I did. He taught me about the wind, the tide and how to navigate. No school could teach me that.” Leslie Sr. in particular was innately tied to the water. “He would be asleep and wake up and say he has to change the boat,” says William of his father. “He felt it in the air. He could tell the tide had changed.”

Kind and quiet-mannered, Leslie Sr. lived on the property his entire life, raising his eight children as well as his grandson Kip. A waterman, family man, churchman, athlete, he was an esteemed member of the community, always at the ready to help anyone and everyone in need. “He was well respected in the area because of his mild manners, the way he carried himself,” says Yvonne. “He was well respected by Blacks, Whites, and financial institutions.” Quiet though he was, “when he started chanting in church, you knew it was him!” says Jimmy. Jimmy also recalls when Leslie Sr. “invented” a mechanism that could make every crab a soft-shell crab using a float with a pump that brought water from the river into the floats on land, resulting in hard crabs shedding into soft shells.

Anytime you come down this road, first thing you think about is grandpop Harry Benjamin, grandfather Leslie Sr. . . . and our other ancestors. Look out at that water and that’s all you see—you see them.

Leslie Sr.’s tie to the water came naturally to him. His father Harry Benjamin was also a waterman and built an oyster house right here on the property—the first for a Black man in this region. Kip still has memories of laying in the hammock outside the oyster house with his great grandfather, snacking on sardines, salt, and vinegar.

Others in the Wilson Family pursued different occupations—law enforcement, marine corps, iron works, real estate, ballet, writing, educational psychology, teaching, to name just a few. But their tie to the water was always strong, even if they didn’t make a living doing it. “The older Wilsons used to say ‘once that water gets in your veins, that’s it. It don’t leave you,’” says Kip. “You have to return to it.”

Environmental stresses like polluted runoff, a changing climate, and more have made working the water more challenging in recent years. “My father used to call it, ‘red water,’” says William of the polluted runoff that causes algal blooms and red tides. “I never thought I would see the day where you can’t make a living on the water,” says Kip.

Ties to Place, Ties to Each Other

These days, though many in the Wilson Family live away from “The Point”—Pennsylvania, Maryland, Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Chesterfield, Washington, Northern Virginia, D.C.—their connection to this land and water is no less palpable. Though they may not have been born here or raised here, it will always be home.

“We all moved away, but we all still come back,” says Darlene . “I thank God to still have a place to come back to. Not every family of color has that to come back to.”

Summer visits, holiday gatherings, family reunions, crab feasts complete with 80 bushels of crabs consumed—all continue to be traditions in the Wilson Family, where connecting to each other is just as important as connecting to this place. “We talk a lot about generations and how family comes together. This place brings us together,” says Cecil Johnson.

Adds Daisy: “We talk about the love of the water and the love of the land, [but] we also need to talk about the religious aspect . . . before the crab feasts, Sunday dinners, any meal, we would come together [to pray ]. . . God has blessed us, we didn’t get here by ourselves.”

Grandpop Harry Wilson with his children.

William Wilson.

Brooke who now owns one of the Wilson Family homes at The Point that her grandfather built, is grateful to share this place with her cousins and the next generation, including her 16-year-old son. “I knew from growing up as a child, visiting in the summer with family, that this place was special. We can never let go of it. And we want our son Grayson to learn about his family and the water here.”

Outside, toward the end of the day, the sun dips lower in that blue bird sky casting a golden hue across the crape myrtles that years ago William planted and that continue to line Route 671—now called Wilson Drive.

It’s hard not to think of Mitchell I in moments like these and what he made possible for his descendants. “This place is so very special to me because of the dream of a Black man in 1877 to own land, and it came true,” says James Douglas.

Perhaps Kip sums it up best when he speaks of the solace and connection he finds with this land and his ancestry: “No matter what you’re going through in life, there’s nothing like coming down here. No matter what’s bothering you, what’s on your mind. For some reason—I don’t know if it’s that tie to our ancestors—but sitting out here, it gives us peace of mind . . . Anytime you come down this road, first thing you think about is grandpop Harry Benjamin, grandfather Leslie Sr. . . . and our other ancestors. Look out at that water and that’s all you see—you see them.”

A memorial to Harry Benjamin Wilson in the form of a well standing at the site where his house once stood. His oyster house would have stood just beyond that at water's edge. The well now stands in memory of all the Wilsons who have passed on.

Byron McKie.