Growing up in the 1960s in the Cradock neighborhood in Portsmouth, Virginia, Peggy Kennedy never thought much about the metal recycling operation on the other side of Paradise Creek known as Peck Iron and Metal.

While the plant has been closed since 1999, today the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) warns that the 33-acre shuttered site still contains highly carcinogenic chemicals such as PCBs, dioxins, and furans, as well as radioactive metals. These contaminants have been found in fish, groundwater, wetlands, and soils.

Now Kennedy suffers from a rare type of blood cancer called multiple myeloma. She can list the names of neighborhood friends with cancer, and her multiple pets that have died from the disease.

Throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed, toxic contamination continues to pose risks to human health and wildlife. More than three quarters of the Bay's tidal waters are considered impaired by chemical contaminants, according to the EPA's Chesapeake Bay Program. The best way to reduce the prevalence of these chemicals is largely the same as reducing excess nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment: stop pollution at its source, before it enters waterways. However, cleaning up legacy sites like Peck remains a challenge.

The Peck site operated for more than 50 years, recycling metal from industry and military installations—including electrical transformers, batteries, tanks, planes, and weapons. The process left behind contaminants from the metals.

High tides and heavy rains wash floodwaters over the contaminated site in low-lying Hampton Roads, polluting waterways, threatening wildlife, and creating a public health risk. Those same waters wash through wetlands surrounding Paradise Creek and inundate yards and parking lots in Cradock.

In 2009, the federal government declared Peck Iron a Superfund site, which requires an EPA cleanup plan. Thirteen years later, those plans are finally moving forward, and a public comment period wrapped up in September. CBF worked with community members to submit comments calling for a strong cleanup plan for the Peck site that prioritizes the community's health and includes public outreach to ensure residents are involved in the process.

Residents in Cradock live within two miles of five Superfund sites, including Peck, meaning they are closer to these toxic places than more than 99 percent of the U.S. population. Still, for decades many locals had no idea of the dangers at the Peck site just across the marsh.

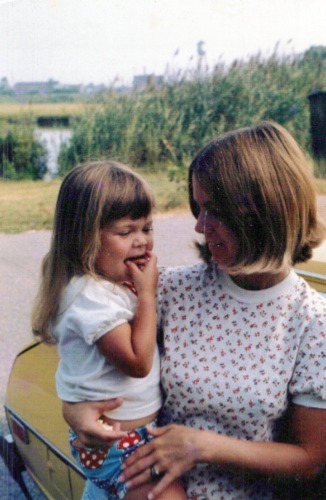

Peggy Kennedy and her daughter, April, along Paradise Creek in the past while the plant was still operating, with Peck Iron and Metal buildings visible in the background.

April Strickland

"For years, my kids swam in our pool, which was filled with well water. We now know that's contaminated groundwater," Kennedy said. "My kids drank from the garden hose and thought the water was rusty tasting. Now we learn it wasn't just rust in that water."

She worries that her now-adult children may be at risk.

"Anybody who has lived in Cradock could have been exposed," Kennedy said. "Who knows how many people are currently sick or will become sick."

Though Patricia Thompson lives blocks away from the waterfront, her Cradock home has a flooding problem due to a storm drain behind her house. Even on sunny days, whenever there's an especially high tide, creek water flows up a stormwater pipe and out the drain, flooding her backyard. Since 2009, her house has been flooded three times, once requiring a major rebuild due to water damage. As sea levels rise and storms intensify due to climate change, this type of flooding is getting worse.

Thompson would like to move, but she worries that nobody will buy a house with a flooding problem near a Superfund site. "The water is awful," Thompson said. "We don't know how it could eventually end up affecting our health. We don't know who it could strike next. Has it already? We don't know."

In comments on the proposed cleanup plan, CBF advocated for EPA to require that any waste left on site have a liner below it, in addition to a cap above, to prevent dangerous pollution from continuing to seep into the groundwater and wetlands. The EPA should also complete a health study of nearby residents to determine how this pollution contributes to cancer rates and other health problems.

Kennedy has joined friends and neighbors in working with local leaders to shine a spotlight on the issues at the Peck site. The EPA has plans to go door-to-door in the community during a two-day visit in late fall 2022, and the Peck site is gaining more public attention through local advocacy and news coverage.

The next steps in the EPA's cleanup plan include addressing groundwater beneath the Peck property, as well as contaminated groundwater, soil, and sediment outside the property boundary. The EPA expects to complete that work in the fall of 2025. There will likely be additional opportunities for public comment before then.

Still, many residents say they have felt neglected for too long.

"They just act like they don't care about us as a community," Thompson said. "With those pollutants and all that mess coming out. That's not good for us. They need to do something."

Editor's Note: Peggy Kennedy's daughter, April Strickland, is a CBF employee. Strickland's position at CBF is not directly related to CBF's work on the Peck cleanup plan.

Issues in this Post

Chemical Contamination Climate Change Community Restoration Runoff Pollution Sea-Level Rise