This is Part One of the History for All series. The series explores the untold history and legacy of people of color in the Chesapeake Bay watershed and their ongoing part in its restoration..

Josephine Williams (left) and Helen Phillips Pitts (right) with photos of John Mallory Phillips and a conch shell found on one of his boats, The Rasmussen, in the late 1800s.

the Phillips family

Helen Phillips Pitts and Josephine Williams have spent the last 20 years rediscovering the history of their deceased relative, John Mallory Phillips. Not a common name in history books, Phillips made waves in the Hampton, Virginia, area by helping the Black community as well as being a successful waterman throughout his life from the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Like many people of color throughout history, Phillips's name has been lost to all except for those in the tight-knit Phillips family. Helen and Josephine, inspired by Phillips's success and his continued effects on their own lives, share his story with pride.

"My father didn't talk about his father very much—but I did hear many things about my grandfather from my relatives, growing up in this area [Hampton, Virginia]," said Helen, John Mallory Phillips's granddaughter. "I think my family wanted to make me proud of where I came from."

While Josephine, who grew up in Philadelphia, didn't get the same amount of information, she still knew of her great-grandfather's legacy.

"My mother didn't talk about her past much, but I knew that John Mallory was an oysterman because my uncle, John Mallory II, was still in the crab business," Josephine added.

Despite their varying familiarity with Phillips's successes in his life, Helen and Josephine have remained undeterred in their research on his unique history.

Phillips was born in 1856 in York County of a Black mother and White father. He lived with his mother up until the age of 14 before being sent to live with his uncle.

"Back then it was thought boys had to be raised by men," Helen remembered.

Phillips lived with his uncle up until 1880, when he was 25.

"He was an oysterman from the beginning," Helen stated proudly. "There were a lot of White oystermen in that area, and he was just as good, but didn't get the credit."

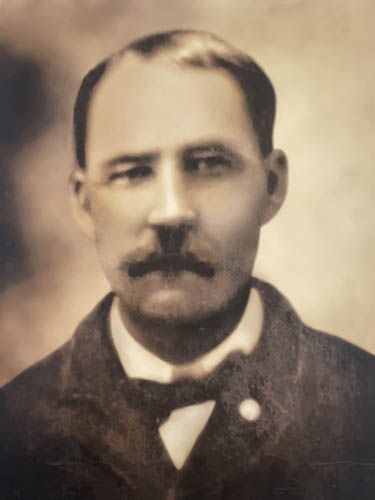

John Mallory Phillips was an influential waterman and businessman in Hampton, Virginia.

the Phillips family

However, Phillips's lack of accreditation in the oystering world didn't inhibit his success. By 1889 he opened a loan bank for Black people in Hampton— one of the few places allowing people of color to take out loans to build homes, start businesses and more—providing a great assistance to the local Black community. Soon after creating the Building & Loan Association, in 1898 Phillips started the Bay Shore, a resort for people of color, which was yet another big step for the Black community of Hampton.

Throughout these endeavors, Phillips remained one of the most successful oystermen in Hampton.

"He had a slew of seven boats, owned his own oyster beds, and owned a hardware store," Helen and Josephine said, looking through their copious notes on their grandfather.

Through research in old phone books, they learned that from 1889-1990, Phillips owned the Hampton Supply Company & Hardware store and was listed as the president in 1900.

And although John Mallory Phillips passed away in 1922, his effects on his community and family live on.

"I grew up with all that he's done," his granddaughter reminisced.

Helen, born in 1948, although raised in a time still controlled by segregation, was able to benefit from roads paved by Phillips without realizing it.

"I took that beach for granted," she said, referring to the resort, Bay Shore, that Phillips funded.

Josephine, Phillips's great-granddaughter, although not raised in Hampton, is still touched by her great-grandfather's success.

"I feel proud of how he was able to progress so much in his times and leave a legacy for his family," she said.

John Mallory Phillips made leaps in the Black community at a time that lacked support or recognition for people of color, and his story should be known nationwide. He is an inspiration, a legacy, and someone who should be thoroughly recognized as a part of American history.