The Supreme Court is poised to begin a new session October 3 with a case folks who care about the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers and streams won't want to miss. Sackett v. EPA involves an Idaho couple the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sanctioned for filling in wetlands on their property without a permit. At issue broadly is how the agency determines which waters are protected by the federal Clean Water Act—and which aren't.

This is important because the federal government can only safeguard waters covered by the landmark law, which aims to protect and restore water quality across the country. But the 50-year-old statute does not explicitly say which "waters of the United States" it empowered the government to regulate.

The Sacketts, who are before the High Court for a rare second time, insist EPA only oversee "navigable" waterbodies connected by surface water. This view ignores the scientific fact that all waters in a drainage basin are connected, even if only underground (a point CBF and other environmental groups made in a joint amicus curiae brief they filed in the case).

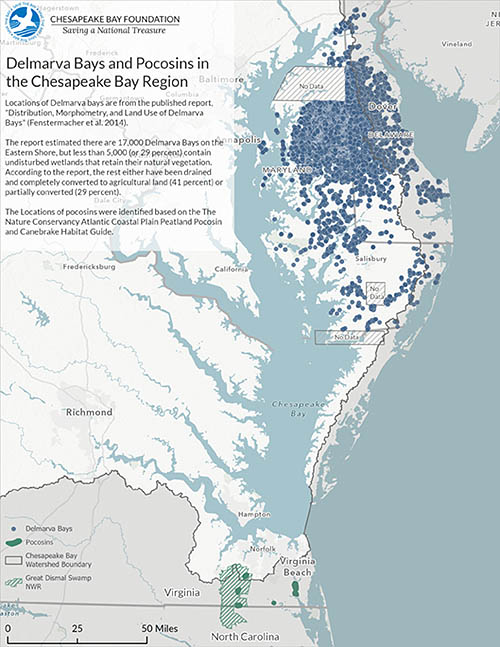

Two types of unique, isolated freshwater wetlands are found in the Chesapeake Bay watershed: "Delmarva bays" (also called "Delmarva potholes") and "pocosins" (pronounced "puh-COE-sins"). (Full Map | Printable Map)

Katie Leaverton/CBF Staff

It also would leave vulnerable to destruction several categories of "non-navigable" waters that are nonetheless critical to restoring and protecting the Bay ecosystem. Among them are two types of isolated freshwater wetlands unique to the watershed: "Delmarva bays" (also called "Delmarva potholes") and "pocosins" (pronounced "puh-COE-sins").

Delmarva bays are shallow, oval-shaped depressions scattered over the Delmarva Peninsula, with most clustered on the Delaware-Maryland border. Roughly 5,000 Delmarva bays covering 34,560 acres contain forested wetlands. Pocosins, only found in the watershed in Virginia, are isolated bogs with sandy, peat soils.

Wetlands are critical to restoring the Bay because they trap pollutants running off farmland, suburban parking lots, and city streets before they can reach the 111,000 miles of local streams, creeks, and rivers that empty into the Bay.

Wetlands also provide essential habitat for fish and wildlife that support the region's multibillion-dollar seafood industry and thriving outdoor recreation and tourism sectors.

By absorbing storm surges and flood waters like sponges, wetlands protect coastal communities from climate change effects like sea-level rise and "sunny day" flooding that threaten lives, businesses, and property.

Another category of "non-navigable" waters at risk—and important to Bay restoration—is streams that don't run continuously all year. They are classified either as "intermittent," meaning they only run seasonally, or "ephemeral," meaning they run only after it rains or snows.

Virginia and Pennsylvania have the most miles of intermittent or ephemeral streams in the watershed. A staggering 59 percent of linear stream miles in Virginia (55,589 miles out of 94,914 miles) are either intermittent or ephemeral streams, according to a 2013 EPA report. In Pennsylvania, intermittent or ephemeral streams account for 41 percent of linear stream miles (30,148 miles out of 74,247 miles), according to the same report.

If the Supreme Court decides that the Clean Water Act doesn't protect Delmarva bays, pocosins, or intermittent and ephemeral streams, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia do have state regulations that could offer some coverage. But loopholes, waivers, and limited enforcement by state officials would leave many of these ecologically important wetlands at risk.

The danger is greater in Delaware, where the state follows the federal definition of covered waters. Delaware estimates around 30,000 acres of its isolated wetlands, including 1,500 acres of Delmarva bays, are unregulated and threatened with destruction. Delaware also does not regulate activities in ephemeral streams, according to the state Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control.

The Supreme Court is hearing oral arguments in the case on October 3, the first day of the new session. However, it will not issue a ruling for several months.

In the meantime, the Biden administration is drafting yet another rule to define wetlands and other waterbodies protected by the Clean Water Act. The move has drawn strong criticism from the Sacketts' congressional supporters, who want the Supreme Court to weigh in first. CBF submitted comments on the rule-making process urging EPA to protect isolated wetlands, including Delmarva bays and pocosins, and seasonal streams.

It's unclear if the new rule or the Court's decision will finally settle this question. What is clear are the significant stakes for the Bay, its tributaries, and the more than 18 million people who live, work, and play in its watershed. Without federal protections for all waterbodies critical to the cleanup, including Delmarva bays and pocosins, our ability to save the Bay is also at risk.