Fifty years ago last month, massive tropical storm Agnes unleashed a torrent of rainfall across the region leading to unprecedented flooding, 122 fatalities, $3.1 billion in damage, and, some say, a forever changed Chesapeake Bay. It was the nation's costliest natural disaster at the time and one ripe with unimaginable human and environmental tragedy.

As famed Chesapeake writer Tom Horton recalls years later: "For the Bay, it was exquisitely bad timing, seasonally speaking. Agnes came when oysters were spawning, seagrasses were flowering, fish were hatching. Massive influxes of freshwater, extending for weeks well south of the Potomac River, were deadly to shellfish. Unprecedented volumes of sediment smothered great swaths of Bay bottom, wiping out thousands upon thousands of acres of underwater grasses."

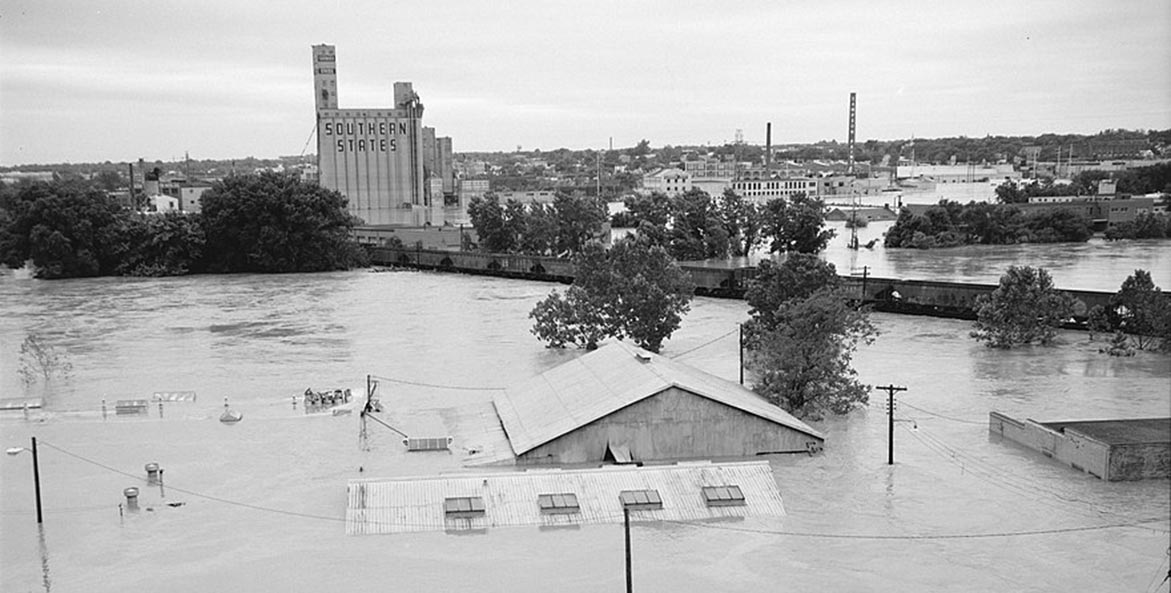

Flooding from Hurricane Agnes in Wilkes-Barre, PA.

National Weather Service via Wikimedia Commons

The excess sediment and nutrient pollution that gushed downstream wreaked havoc on everything in its path. Horton reported for the Washingtonian, in Washington, D.C., alone, "the Potomac River crested Saturday, June 24—made chocolate with topsoil washed from a nearly 15,000-square-mile watershed and swollen to about twice its normal width. Refrigerators from Pennsylvania, pieces of turkey houses from West Virginia, caskets from a local mortician—the quantity and diversity of the debris moving downstream were remarkable."

CBF's own Mary Tod Winchester, former VP for Administration (and the organization's fourth employee) remembers the storm vividly. She recently told the Bay Journal, "that was one of the things about Agnes. It was a wake-up call, and it really helped to ring the bells that there was a problem here." In the aftermath of the storm, half of all underwater grasses in the Bay were wiped out, the shad fishery was decimated, and the soft shell clam population was nearly erased.

With the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) again predicting "above-average hurricane activity" this year (the seventh year in a row, mind you, with that prestigious distinction), what does the future hold for hurricanes and the Bay? And moreover, what can we do about it?

The I-95 bridge leading into Downtown Richmond, VA remained partially submerged in flood water two days after Hurricane Agnes.

Library of Virginia via Wikimedia Commons

As we saw with Hurricane Ida last summer, stronger and more intense storms are unfortunately here to stay (thanks, climate change). But as CBF's Director of Science and Agricultural Policy Beth McGee says, "while heavy rains will always mean more pollution to our waterways, there are many things we can do to reduce runoff." Using nature's natural power to play defense against these storms and their aftermath is key. McGee continues: "Planting streamside forested buffers and wetlands will slow the flow of water and suck up nutrients and sediment. Farming practices like cover crops, no-till and rotational grazing lead to healthier soils that have a higher capacity to soak up rainwater. In our urban areas, more 'green infrastructure' such as trees and rain gardens will similarly reduce runoff by allowing more rain to infiltrate back into the ground."

So while storms like Agnes and Ida may continue to haunt us, we can better prepare for and lessen the inevitable devastation they will cause. The answer lies in our natural infrastructure: leafy, green trees, healthy soils, rich rain gardens, and robust marshes and underwater grasses.