The concerning results of the 2022 Chesapeake Bay blue crab dredge survey should be a warning sign to state fishery managers.

The total number of blue crabs estimated in the Bay this year—227 million—is the lowest number since Maryland and Virginia began the cooperative crab survey in 1990. This year marked the third consecutive year when juvenile crab numbers fell below the survey's average and the overall population declined.

The juvenile numbers are of particular concern. While this year's juvenile population estimate increased slightly from last year, from 86 million to 101 million, this figure is well below the 219 million average population of juvenile crabs in the survey.

Crabs typically have a three-year lifespan, meaning the juveniles counted in this year's survey will become the adults reproducing later this year as well as those harvested for the dinner table. Without a significant rebound in the juvenile population, it's possible the declining overall number of crabs could continue in the future.

What can be done? In the short term, we need to protect crabs this year to maximize reproduction. This will require a reduction in the blue crab harvest. However, long-term actions are also needed to address the trend of low crab reproduction, such as loss of crab habitat and increased predation.

This year, state fishery managers could tweak some of the crab fishery regulations such as bushel and season limits. Managers use female crab population estimates to determine whether fishing effort is sustainable. Currently the adult female population is about 97 million crabs, above the management threshold of 72.5 million crabs, meaning the female crab population is not overfished. If the female crab population falls below that threshold, then there is a greater chance that the population can't reproduce quickly enough to withstand fishing pressure and environmental stressors. Already, both Virginia and Maryland are considering measures to reduce crab harvests in the state by approximately 10 percent.

Managers should also consider options to protect male crabs, which fell to the lowest population recorded in the survey—28 million. A 2003 study published in the Bulletin of Marine Science found that large males tend to be more successful in reproducing, suggesting there may be value in preserving the largest male crabs. In Maryland, almost all regulations focus on limits for female crabs, but few protections are provided to adult males.

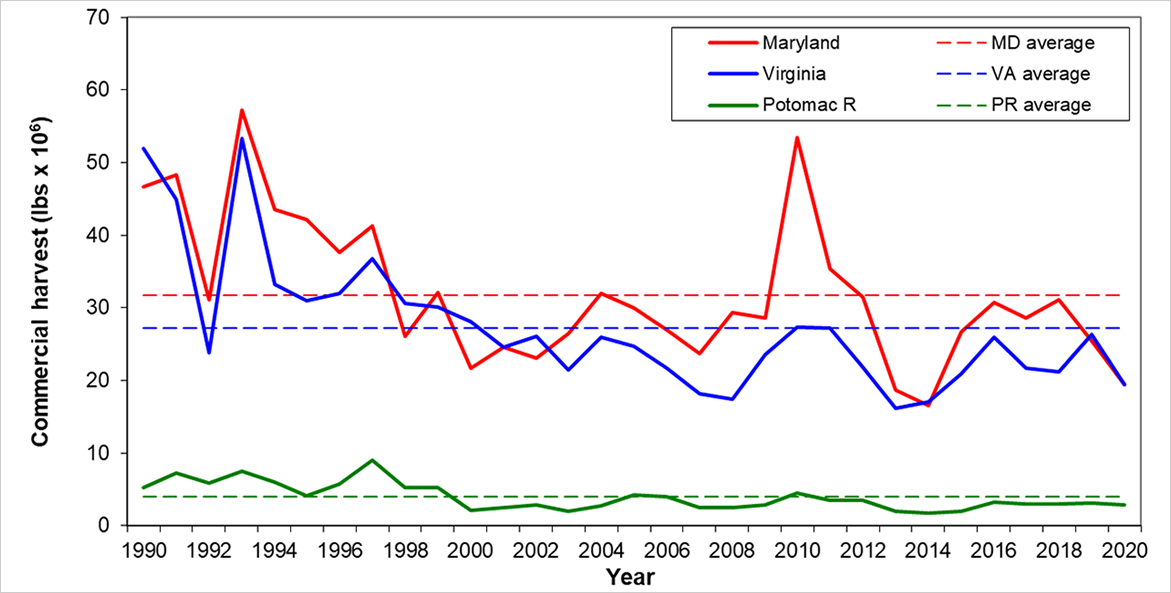

Changes to fishery regulations may frustrate watermen who depend on catching crabs for their livelihood. But harvest figures align closely with population survey estimates. Reversing the recent population decline should result in greater harvests in future years.

Maryland, Virginia, and Potomac River commercial blue crab harvest in millions of pounds (all market categories), 1990-2020.

2021 Chesapeake Blue Crab Advisory Report

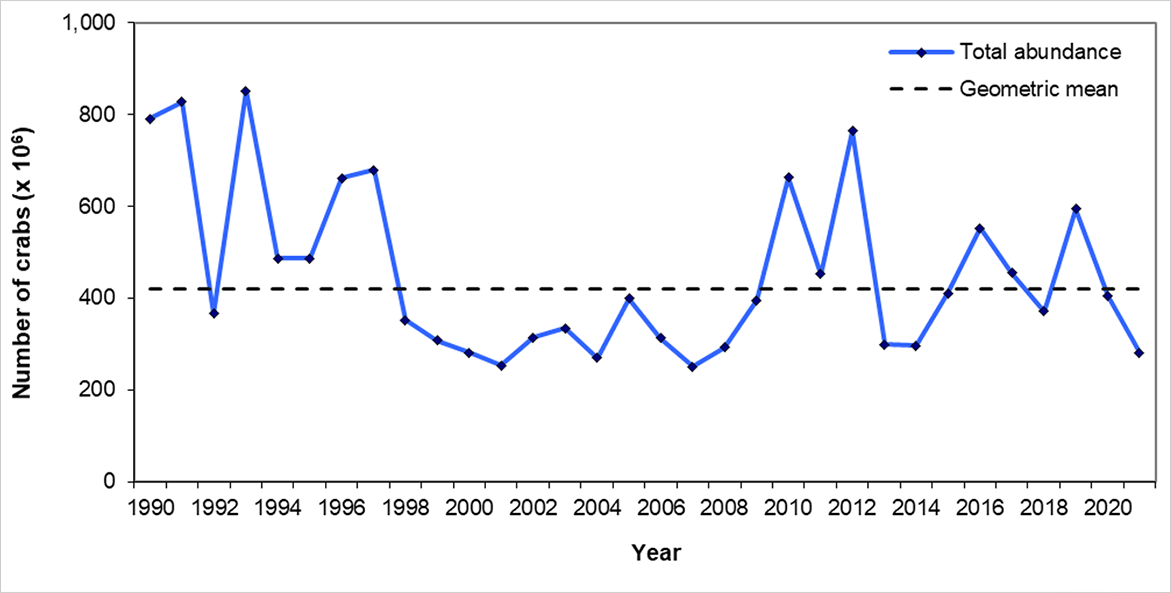

Winter Dredge Survey estimate of abundance of all crabs (both sexes, all ages) in Chesapeake Bay, 1990-2021.

2021 Chesapeake Blue Crab Advisory Report

The long-term environmental stressors likely affecting crab populations such as nutrient pollution, declining acreage of underwater grasses, and proliferation of invasive blue catfish that prey on crabs are more difficult to address.

CBF has been encouraging recreational anglers to target and harvest blue catfish, a voracious predator of native species like blue crabs, to help reduce their harm to the Bay's ecosystem. We're also advocating for the federal government to reverse a duplicative and wasteful food safety inspection requirement for catfish species to enable local watermen to more easily sell blue catfish.

Underwater grass acreage in the Bay declined recently to about 60,000 acres, according to the most recently available data, after hitting a record of 108,000 acres in 2018. Grasses provide protection to juvenile crabs, which use them to hide from predators. However, the grasses are susceptible to sediment pollution and algal blooms that cloud the water and prevent sunlight from reaching the Bay bottom. Lack of sunlight prevents the grasses from growing.

Efforts to reduce the nitrogen and phosphorus pollution that fuel algal blooms in the Bay are under way with Maryland and Virginia plans mostly on track to meet 2025 Bay Clean Water Blueprint goals.

However, Pennsylvania continues to lag in meeting its reduction requirements, largely as a result of pollution from farms. For years, CBF has promoted regenerative agriculture methods that restore soil health and add more natural filters such as trees and landscaping to both farms and cities to reduce these sources of pollution.

The silver lining in this bad news is that crabs have an incredible ability to bounce back in response to quick action by fishery managers and the right environmental conditions. In the mid-2000s the Bay's blue crab population suffered significant declines leading fishery managers to place new limits for harvesting adult female crabs and close the winter dredge fishery for crabs. Those changes created relative stability in the Bay's crab population before the three-year decline began in 2020.

Today, we're at a similar point where scientists must research what's contributing to the species' decline, while fishery managers swiftly work to reverse it.