In July of 1978, I interviewed for a job with CBF and met Will Baker. He was the newsletter editor at the time, having started as an intern two years earlier. We all know the rest of the story—how he went on to become CBF's president and lead the organization to great success. For me a few anecdotes along the way appropriately humanize the intern-cum-president and help flesh out the story.

I first worked on fisheries for CBF in 1984 right at the height of the rockfish debate. Fresh from grad school, my view was couched in what science could or could not tell us. Will did not share my restraint—in his gut he felt the rockfish needed immediate relief from fishing pressure in the form of a moratorium. I'll never forget the meeting with DNR officials when Will really laid on the guilt trip about the future of our state fish (and the Bay itself). I was learning about advocacy; he was practicing it.

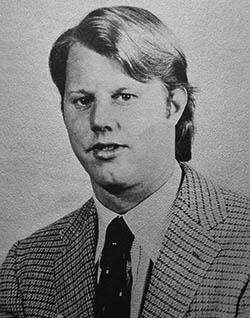

Will Baker, from CBF's 1979 annual report.

CBF

Looking back on that period, I prefer to see CBF as breaking new ground in our rockfish advocacy. Previously only fishermen groups were engaged in Chesapeake Bay "fish politics" in order to represent their interests, whereas our role, as we saw it, was to represent the fish. At the time, however, we were viewed as interlopers. The watermen, charter captains and sport fishermen all thought we should stick to pollution issues and stay out of fisheries. Outdoor writers made that clear, including in the Washington Post where we were infamously referred to as "tweedy" as if to say we were preppy dilettantes. No one knows for sure, but Will's picture in CBF's 1979 annual report suggests the origin of that insult.

Undaunted, Will continued to establish a role for CBF in representing the resource in the public forum. Instead of that mouthful, however, the term "watchdog" for the Bay was often used. In a 1987 letter to the editor of The Annapolis Capital opposing a proposed development on Smith Island, Will mustered his best Terminator by concluding in serious tone, "...CBF will be watching." A tweedy watchdog is not to be messed with (and indeed, the development was never built).

By the early 1990s we were embroiled in another fisheries controversy, this time about oysters, having called for a moratorium in that fishery in 1991. For years after that, Will pressed for us to build a three-dimensional oyster reef to show it could be done and what it would mean for oysters and the Bay. I resisted—after all, we would need engineers for that! And heavy equipment!! But sure enough (and after a few other notable steps), by 2001, CBF was christening a state-of-the-art oyster restoration vessel (thank you, Keith Campbell) and building reefs.

Rest assured, in the midst of our extensive restoration and advocacy efforts, we did find occasion to embrace the "work hard, play hard" philosophy. For those of us privileged to witness it, the most enduring image of Will, perhaps because it was repeated many times over the last twenty years, is from the poker games occasionally organized by a half dozen CBFers. And some of the most memorable games were held on Will's sailboat, even in the dead of winter, tied up in its slip in Annapolis harbor.

There, the saga of the Baltimore Burner was born. Acey-deucey is a simple game, but with the right dealer it can become a dramatic, high-stakes contest. Each player in turn is dealt two cards face up and must bet whether or not the third card will fall between them. And if it matches one of them, you have to double the pot. Somehow Will had the uncanny ability to deal a matching card when the odds were long and the pot big and thus "burn" the player. And the Baltimore Burner, as he was soon known, played it to the hilt. Seeing him in that role was unforgettable, not just for the amusement, but because here was the CBF President, usually seen as intense, focused, stressed (& stress-inducing), letting it all hang out. And without any tweed in sight.