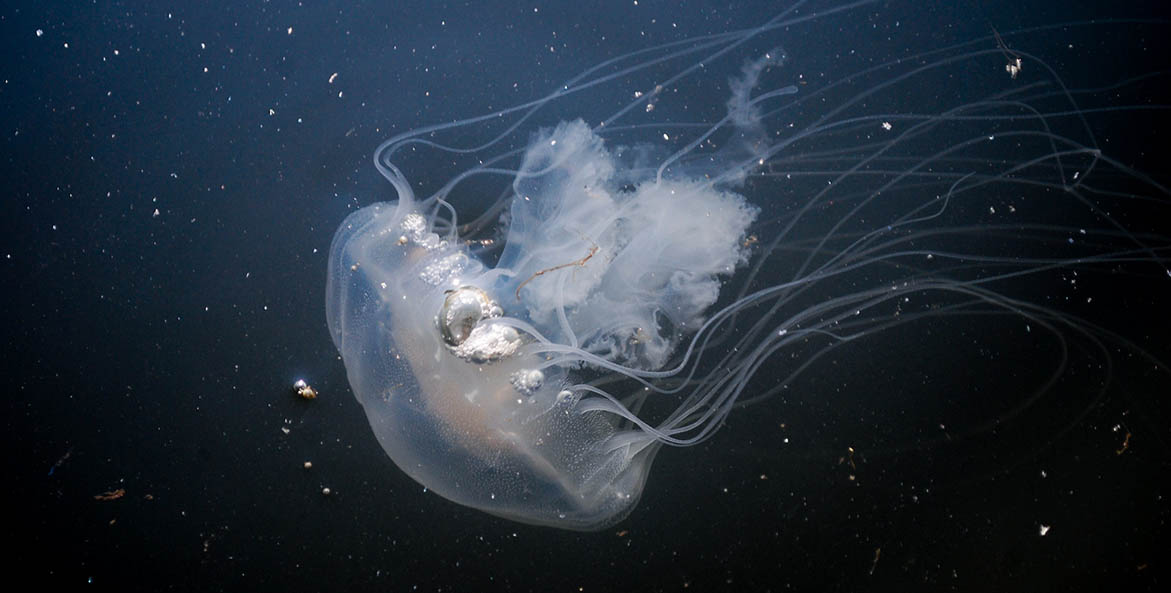

For me, a childhood summer on the Chesapeake was not complete without jellyfish (or what we not-so-affectionately called stinging nettles). Long, hot afternoons in the water spent squealing and dodging nettles was as natural as barefeet romping or blue crab catching. Despite the uncomfortable sting they inflict, jellyfish have long fascinated. There’s something otherworldly, even graceful, about these pulsing, gelatinous animals.

While we haven’t seen the invasion of the jellyfish quite as much as we did last summer, we are keeping a close eye on NOAA’s experimental tool that predicts sea nettle probability across the Bay. Latest forecast shows overall the Rappahannock River north to the Choptank as the areas to watch for larger concentrations of nettles. In addition to checking out this resource before plunging into your favorite Bay river in the remaining weeks of summer, here are some other interesting facts about nettles that may surprise you:

1. Jellyfish use their stinging tentacles to capture prey

It’s hard to believe (and see), but these pulsing, jelly-like creatures actually have mouths. They eat fish, comb jellies, algae, and more by using their stinging tentacles to entangle and paralyze their prey. They then move the food to their mouths, located under the center of the umbrella-shaped bell (or medusa) at the center of their bodies and from which the tentacles hang.

2. Jellyfish populations are increasing

To the dismay of many a Bay swimmer, research has shown that jellyfish populations are actually growing. Raleigh Hood, biological oceanographer and professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Horn Point Laboratory says, “On a global scale, we think jellyfish populations are increasing and that appears to be linked to two factors. One is nutrient pollution, which is causing there to be more algae in the Bay and more food, which is beneficial to the jellyfish . . . The other factor that we think is contributing to long-term increases in jellyfish is overfishing. When you take the fish out of the water, the fish compete with jellyfish for food, so you’re just making more food available for the jellyfish.” In other words, the more we can fight pollution through the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint and restore balance to the Bay with healthy fish and sea turtle populations (which eat jellyfish), the more we may be able to control the nettle population.

It is worth noting that summer to summer, depending on weather conditions, jellyfish numbers fluctuate. In general, nettles thrive in dry, hot weather so we're less likely to see them after a heavy rainstorm that washes freshwater into the Bay and drives down the salinity. Even more interesting, however, is the fact that jellyfish, whether we like it or not, are always with us. In mid to late summer, jellyfish spawn. A female’s eggs are fertilized when a male releases sperm into the water, which is then pumped through the female’s body as she swims. Once fertilized, eggs develop into tiny, free-floating larvae which the female then releases into the water where they float with the current and then attach to a firm surface. They will remain there as dormant polyps through winter until warmer weather induces them to break free and develop into floating medusa and eventual mature adults—if conditions are favorable.

3. There is actually something good about stinging nettles

Interestingly, jellyfish are a friend of the oyster—a valuable and iconic part of the Bay ecosystem. Bay nettles and comb jellies both prey on oysters when they are in their floating larval stage. But while comb jellies catch and digest larval oysters, nettles spit them out unharmed. In fact, sea nettles actually help protect oyster larvae by snacking on those comb jelly oyster predators.

4. Everyone has an opinion about how to treat jellyfish stings

Baking soda, meat tenderizer, vinegar, alcohol, hydrocortisone creams, even urine—there are many theories out there about the best way to treat a jellyfish sting. Most agree that rinsing the sting area with Bay water (not fresh water) before liberally sprinkling a meat tenderizer or baking soda to the area is the best way to go to alleviate the sting. For what it’s worth, baking soda is my go-to.

Discover more about these fascinating creatures in our latest Chesapeake Almanac podcast