When Daniel Klein became a volunteer CBF Clean Water Captain in 2018, he had no idea it would lead him to spearhead an effort to give away thousands of native trees in the middle of a pandemic. But he jumped into action this year when he heard about redbud saplings in need of a Virginia home.

The 12,000 trees were left over from a project led by Dominion Energy that was stalled by COVID-19. The redbuds had nowhere to go. When Klein found out, he quickly worked with the City of Richmond and local organizations to set up more than 40 outdoor giveaway sites manned by an army of volunteers wearing face masks.

They spread the word through social media and the local press, providing information through a new Reforest Richmond web page. Over the course of three weeks, they gave away 8,000 trees for people to plant in their own backyards. They also found room to install 4,000 more at local parks and schools. In the years to come, bright redbud flowers will fill the city with color every spring.

The project created hope during what’s been a very tough year. “Planting a tree is a really great way to participate in a brighter future,” said Klein, a Richmond-area native. “It’s my way of showing my love for Richmond.”

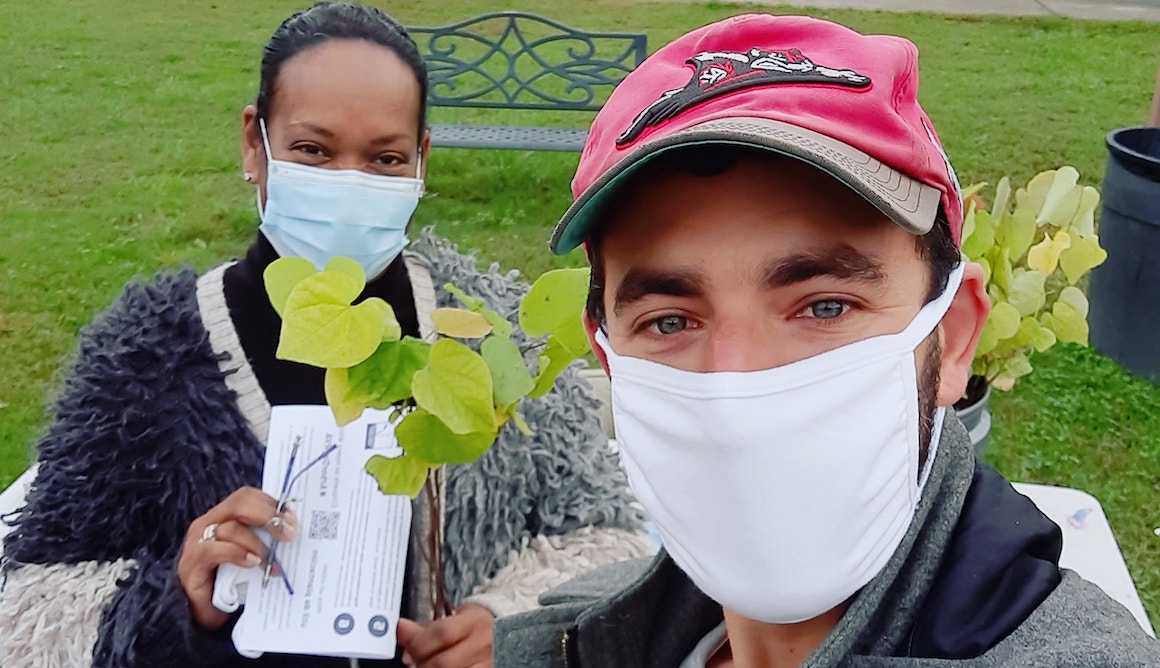

You might not be able to tell because of the masks, but Daniel Klein (right) and those who got free saplings were all smiles!

Daniel Klein

People who had no idea about the project would walk by a giveaway site. “I’d ask them ‘Would you like a free tree?’ They’d stop a moment, smile, and say ‘Yeah!’” Klein said. The passerby would go home with a few redbud seedlings and planting guide, ready to help “Reforest Richmond”—which is the name of the public-facing branch of the Richmond Tree Committee.

Expanding urban tree cover offers solutions to many issues cities face, Klein noted. Their leaves and branches can capture heavy rainfall, reducing polluted runoff and local flooding. But the co-benefits go beyond that.

“You have folks who care about trees because of biodiversity and habitat, and then you have people who care because of opportunities to dismantle systemic racism,” Klein said. “Others care about trees because of their benefits for climate resiliency and urban heat island effect. Trees are a perfect meeting place that so many people care about.”

Recent research spotlighted the issue in Richmond, where neighborhoods suffer from extreme heat linked to redlining, a discriminatory lending practice that decades ago denied investments in predominantly Black communities. Today these neighborhoods still have more asphalt and fewer trees, making them up to 16 degrees hotter than leafier parts of the city.

Klein traces his interest in trees directly to the Clean Water Captains, a group of extremely dedicated volunteers CBF trains and supports in advocacy and restoration efforts. “I do pretty much all of this work thanks to the CBF,” Klein said, noting that he learned about the many benefits of trees during his time as a Captain. “Clean water captains have changed my career trajectory. Now I’m exploring grad school programs for urban forestry.”

As a CBF Captain, Klein took his first forays into advocating for state policies to benefit the environment, reaching out to Virginia legislators and attending meetings on state legislation. But he soon became drawn to local action, focusing on what he could do to help both Richmond, the James River, and waters downstream in the Bay.

That led him to trees. Klein dove right in, forming the Richmond Tree Committee under the Richmond Green City Commission. A broad group of partners joined the mission.

Klein had already spent months working with partners on the commission when the opportunity for free redbud trees came along. They were ready to quickly spring into action. In addition to the City of Richmond, groups that contributed included Southside ReLeaf, Groundwork RVA, the Richmond Community ToolBank, Self Made Roots, the Virginia Department of Forestry, City of Richmond Urban Forestry division, RVA H2O, RVA Green 2050, Enrichmond TreeLab, Capital Trees and more.

The thousands of redbud trees now growing as part of this effort could become a gateway for more plantings. Klein hopes many of the redbuds will eventually serve as an understory for larger hardwood trees like oaks, tulip poplars, and sycamore.

“It was refreshing to see how many people were excited about this. People need hopeful things to do right now, activities that help create the world we want to live in,” he said. “Slowly, we’ll truly begin to reforest schools, parks, and Richmond as a whole.”