Excessive heat, discriminative housing practices, and trees are three things that may not immediately seem connected, but in Richmond, Virginia, their connection is coming to light.

Through a National Fish and Wildlife Foundation grant, the Greening Southside Richmond Project will plant trees, create green space, and remove heat-absorbing concrete and asphalt from Southside Richmond communities. These neighborhoods were historically harmed by redlining, leaving them sweltering and causing residents to have higher rates of chronic illnesses. Through the grant, CBF and partners not only want to help improve the health of the James River and Chesapeake Bay, but also the health of long-term residents.

Get the story straight from members of Southside ReLeaf, Friends of Swansboro Park, and CBF as they share more about these combined efforts in this short video.

How racist housing policies have left neighborhoods sweating

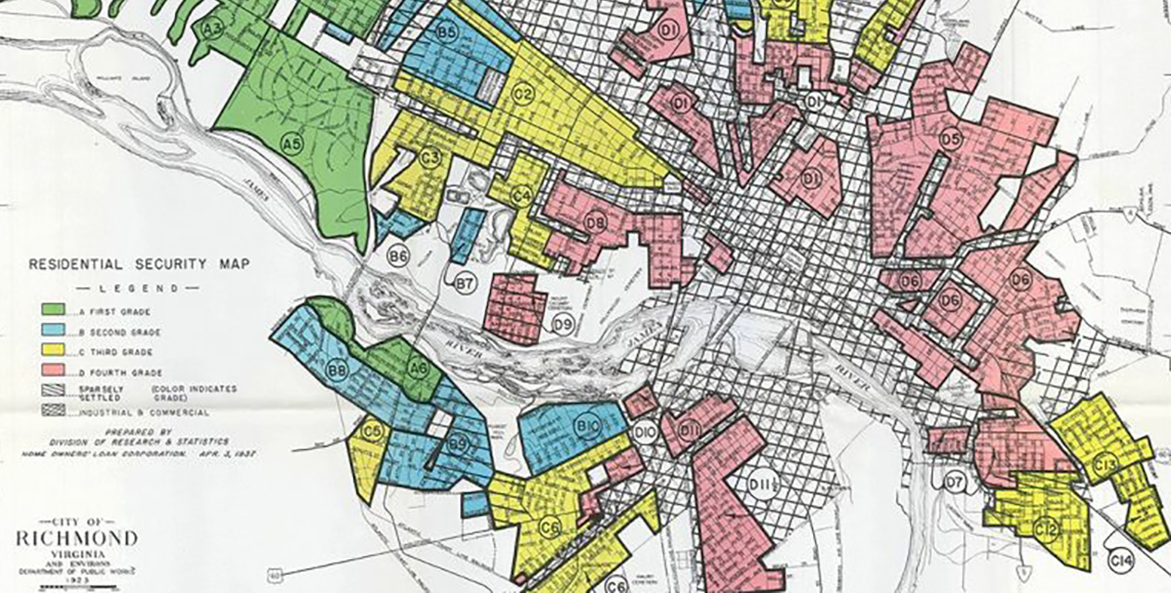

In the mid-20th century, the federal government created maps of cities across the U.S. that rated the risks of different neighborhoods for real estate investment by grading them on a color-coded scale that ranged from “best” (green) to “hazardous” (red). As detailed by the New York Times, race played a significant role. Black and immigrant neighborhoods were typically rated “hazardous” and outlined in red. Redlining was born. For decades, bankers and other lenders were able to deny mortgages and investments in these redlined neighborhoods, fueling a cycle of disinvestment.

While Congress and the courts formally banned the practice decades ago, it continues to hurt communities nation-wide. According to a recent study by the Science Museum of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, and Portland State University, formerly redlined neighborhoods can be 5 to 12 degrees hotter than other parts of the same city due to their lack of trees and green space. These formerly redlined neighborhoods also tend to have more heat-absorbing concrete and asphalt that increase temperatures and puts residents at risk for heat-related illness and death.

Going green to beat the heat

Thanks to a grant from National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, a new initiative in Southside Richmond will plant more than 650 new trees—which provide shade and release water vapor to cool temperatures—in neighborhoods suffering from extreme heat and heat-related illnesses. The two-year Greening Southside Richmond Project will educate homeowners on the value of trees, train local youth for green jobs, transform asphalt into green space, and begin the process of cooling some of the hottest neighborhoods in Richmond.

Members of Branch’s Baptist Church help plant a tree on the church property in 2018.

Kenny Fletcher

Community partner Southside ReLeaf will work closely with community residents to ensure they are involved from day one and that we have community buy-in for the project. “That’s really the only way for any project to be successful,” said Southside ReLeaf co-founder Sheri Shannon. “We can’t just plant a tree or say we’re going to do a community garden and say that the work is done. It takes education, community engagement, and of course follow-up to make sure that young trees or any of these green spaces are able to survive and thrive.”

“With that education for the community we’re talking about all the wonderful things about trees and the benefits they provide, but we’re also looking at the historic context of how we got to this place and figuring out how as a community we can start to dismantle redlining and move toward a ‘greenlining’ process,” explained Sheri.

These locations aren’t chosen at random. CBF used the Richmond Office of Sustainability’s Climate Equity Index map to identify Southside census tracts where green space is most needed to reduce heat and improve the health of residents. Residents in these census tracts are 86% African American and Hispanic. As partners in the project, the city’s departments of Public Utilities and Parks, Recreation and Community Facilities identified parks and community centers in Southside that need more shade.

And as the trees grow, CBF and partners hope they will shade Southside Richmond’s long-term residents for years to come.

“This notion of really being intentional about greening spaces where people without access to resources not only will live, but will be able to live, and having those conversations is very important…. Folks who have paid the price will also reap the benefit,” said Rob Jones, Executive Director of grant partner Groundwork RVA.

And the work doesn’t just end after the project’s two years. “We hope this grant will be a starting point for other great projects,” says Ann Jurczyk, CBF Director of Outreach and Advocacy. “We have pulled together a coalition of partners who each contribute unique expertise to ensure our success. With luck, that success will attract additional private investment and funding partners who want to complement these efforts.”

What’s this all have to do with the health of the Bay?

While the shade provided by trees helps keep communities cool and reduce electricity bills, they also have significant benefits for the Bay.

During rain events, polluted runoff carrying things like litter, soil, and car oil, washes off hard surfaces and streets directly into streams and rivers. Trees slow and absorb large amounts of runoff, reduce flooding, and stop harmful pollutants from entering rivers, streams, and the Bay.

Trees and other plants also help improve air quality. Trees act as lungs, absorbing carbon dioxide and emitting oxygen. They’ve been called “livers” of the ecosystem as well due to their ability to adsorb atmospheric pollutants and fine particulate matter through their leaves.

Residents of formerly redlined neighborhoods tend to have higher rates of chronic illnesses, like diabetes, heart disease, and COPD. These new trees and green spaces will not only cool temperatures and improve air quality, trees and green spaces have been proven to reduce stress and lower blood pressure, improving the health and quality of life of local residents.

As Oscar Contreras, Deacon at Branch’s Baptist Church—where a half acre of asphalt will be removed and replaced with trees—said, “We’re going to be making history and setting an example for other churches and other communities. Instead of losing trees to growth, we can plant more trees in our cities as we grow.”

The Greening Southside initiative will be a model for how unused paved areas and neighborhoods lacking tree canopy can be transformed, beautifying an area while benefiting the environment and people.