Over the last week, reports of rust-colored water and dead fish in the tidal rivers of the mid-Chesapeake Bay have appeared in the news. These are signs of a naturally-occurring phenomenon, called a mahogany tide, that is exacerbated by human sources of nutrient pollution that cause excessive levels of nitrogen and phosphorus to wash into the Bay and its tributary rivers.

We asked CBF's Maryland Senior Scientist Doug Myers to explain what a mahogany tide is, why it occurs, and what it means for the health of the Bay.

Why are we seeing a mahogany tide in the Bay now?

It is a common occurrence in the spring as the water warms up. This year's bloom is especially widespread. It usually pops up in one or more tributaries at a time as the conditions for its rapid reproduction (salinity and temperature) occur. But it popped up in quite a few tributaries this year after a prolonged period of clear water and expanding seagrass beds.

Where is it in the Bay and how long might it last?

This year's tide has been seen from Back River to the Potomac River on the Western shore and the Chester and Wye rivers on the Eastern shore. The most severe outbreaks seem to be in the Severn River and Magothy River, where fish kills are occurring. It has already dissipated from tributaries with good tidal flushing, like the West and Rhode rivers, but will take longer to dissipate where residence time for the water is longer.

How do mahogany tides affect fish, wildlife, and humans?

While not a direct threat to humans, fish and invertebrates caught in a mahogany tide are at first irritated by the large number of cells in the water. As the bloom persists, the decomposition of dying cells depresses the level of dissolved oxygen, killing fish. If the bloom lasts a long time, the shading effect can also kill underwater grasses, which could add to the decomposition problem locally.

What does the mahogany tide mean about the health of the Bay?

Where mahogany tides happen, the affected tributary can see discolored water, dead fish, foam, and the smell of decomposition that could last for several weeks. Eventually, the bloom will subside. The mainstem of the Bay and saltier areas to the South should not be affected. Human sources of nutrient pollution cause blooms to be more severe and last longer than they would normally. It is therefore critical to continue and accelerate implementation of the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint to reduce pollution.

While no one likes to see a bloom, it is important to note that this year's bloom follows a prolonged period of clear water and expanding underwater grass beds. Efforts to reduce pollution in accordance with the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint—the historic federal-state plan to restore the Bay watershed—are working. Over time, underwater grasses are becoming more resilient and the Bay's dead zone—a seasonal area of low oxygen caused by algal blooms—is getting smaller. But as the mahogany tide reminds us, the recovery is fragile, and the road to finishing the job is steep, underscoring the urgent need to continue pushing forward with implementation of the Blueprint across the watershed.

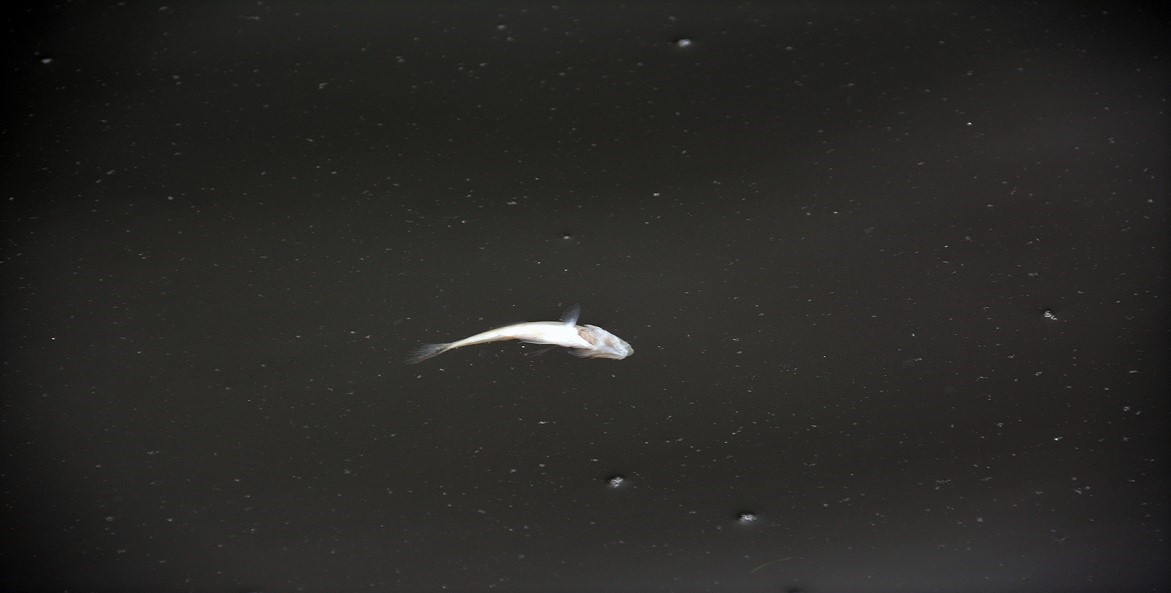

A mahogany tide can be seen along the Severn River in June, 2020.

Rob Beach