In mid-February, the marshes of Dorchester County are flat and cold. The wind is bone chilling. Tundra swans float down from a gray sky to settle in stubbled cornfields. This is where Harriet Tubman, famed conductor of the Underground Railroad, was born into slavery nearly 200 years ago.

Tubman is a formidable figure in American history, her name inscribed in textbooks and learned in schools across the country. But it's here, on the Eastern Shore, where her humanity becomes palpable. Where she transcends the stoic portrait of so many history books and becomes a young woman who faced the excruciating choice of leaving her family and found the immense courage to rescue them.

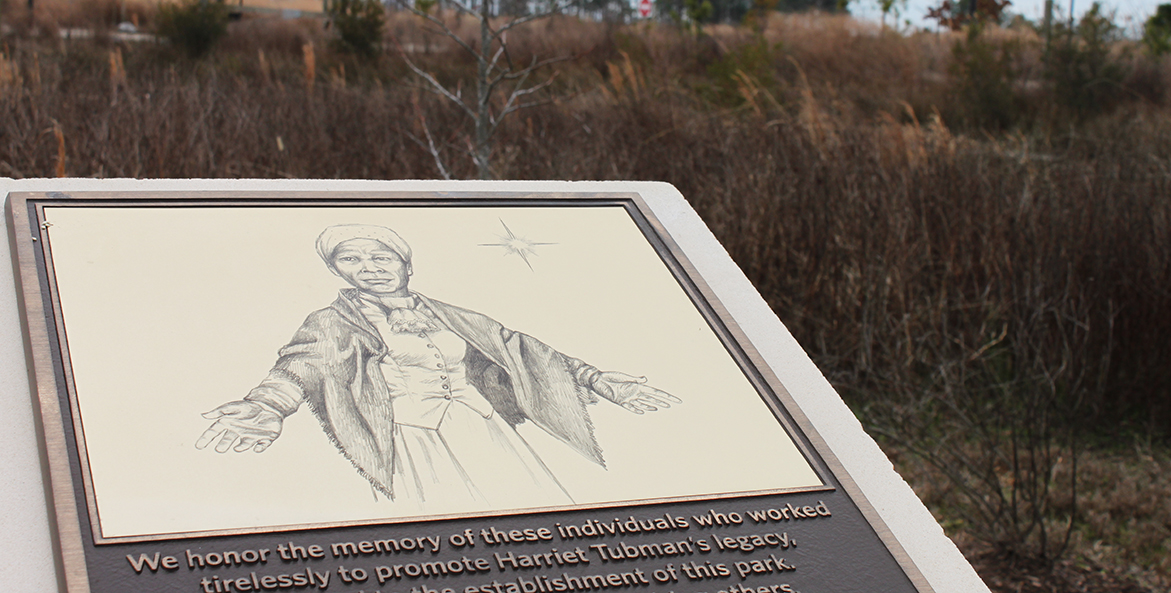

"I think sometimes people see Harriet Tubman as six-feet tall with a cape and the ability to shoot flames from her eyes," says Angela Crenshaw. "She was really just a five-foot-tall African American woman. And she accomplished amazing things."

Codi Yeager / CBF Staff

Crenshaw, who serves as the Assistant Manager of Maryland's Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park in Church Creek, says the reality is even more compelling than the legend. And it is inseparable from the Chesapeake landscape in which Tubman grew up, labored, fled, and returned to more than a dozen times to rescue others.

"The landscape is an interpretive tool," Crenshaw explains. "A lot of the buildings are gone, but we're surrounded by Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. We can use the landscape to interpret her life and her legacy."

It was a harsh landscape for Tubman. Separated from her parents at just six years old, she was farmed out by her owner to work for nearby families. One of her early tasks was trapping muskrats in the marshes, a job that often would have been numbingly wet and cold. Later, she labored in the timber fields near Parsons Creek, hauling logs across the muddy ground to Stewart's Canal—a seven-mile waterway hand-dug by slaves to float timber to Madison Bay.

Her knowledge of the land and her comfort with the inhospitable environment, born of necessity, later became invaluable. So, too, did her interactions with free African American watermen, known as Black Jacks, who offered information about the world beyond the Eastern Shore.

Harriet Tubman was separated from her parents and sent to work for nearby families when she was just six years old. Years later, after she escaped slavery, she returned to rescue many of her family members, including her mother and father.

Codi Yeager / CBF Staff

At 27 years old, she fled the Poplar Neck plantation in Caroline County and traveled more than 100 miles north to escape slavery in Philadelphia. Over the next decade, she guided more than 70 other enslaved people to freedom through the Chesapeake's forests and marshes.

The details of those journeys remain foggy, Crenshaw says—it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read or write, so Tubman was unable put her own story down on paper. But the conditions would have been grueling.

Most of Tubman's rescues occurred in the fall and winter months. Freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad traveled by night, and winter provided long, dark hours. Cold weather also brought firmer ground in the soggy marshes, and some relief from the biting flies and mosquitoes. Still, there would be the constant discomfort of hunger and wet feet. Many enslaved children did not get shoes until they reached a certain age, Crenshaw says, because they were not considered likely enough to live or to have as much value as adult workers.

"When I go hiking, I have hiking clothes; at work, I have wool pants and steel-toed boots," she says. "They didn't have any of that."

The visitor center for Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park is also the site of the National Historical Park of the same name, which Congress created in December 2014. The parks are surrounded by Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge.

Codi Yeager / CBF Staff

After days in the marshes, a fresh set of clothes became a matter of survival. Station masters on the Underground Railroad would provide freedom seekers with clean clothes so when they reached cities like Philadelphia, they could blend into the crowd without arousing suspicion. If they didn't, they risked recapture under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which allowed the capture and return of enslaved people who had escaped, even if they lived in northern states.

It was a tenuous life, Crenshaw says, even for Tubman. After her time on the Underground Railroad, she served in the Union Army as a nurse and spy in South Carolina, becoming the first woman to lead a successful U.S. military raid. In New York, she founded a home for elderly African Americans, married a Civil War veteran named Nelson Davis, and raised their adopted daughter, Gertie. She continued to work for equal rights for African Americans and women.

"It's a sad story, and a painful story," Crenshaw says. "But it's also a hopeful story."