Tropical Storm Lee ripped through central Pennsylvania in 2011 with a fury.

"The building where we're sitting was under 8 feet of water," says Mike Callahan, gesturing around the conference room of the Derry Township Municipal Authority in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

It's hard to imagine, given the docile curves of Swatara Creek gliding just beyond a curtain of trees several hundred yards to the north. But eight years ago, the storm-swollen river blew past its 7-foot flood stage and kept going. It crested at 26.8 feet—a full 10 feet higher than the previous record set in 2006. The rush of water buckled roads, washed out major bridges, and destroyed hundreds of homes and businesses. One person died as a result of the storm. The iconic Hersheypark, just down the road, closed for days.

Yet as terrible as the damage was, it helped position Derry Township and the Derry Township Municipal Authority at the vanguard of a growing movement to re-envision stormwater management.

Historically, streams were channelized with concrete infrastructure to funnel stormwater off the landscape as quickly as possible. Development and extreme storms are putting more pressure on these aging systems, contributing to poor water quality in many Pennsylvania rivers and the Chesapeake Bay.

Codi Yeager/CBF Staff

Like many municipalities across Pennsylvania and the Chesapeake Bay watershed, the township faced an increasingly difficult balancing act between limited resources, aging infrastructure, and regulatory requirements to restore clean water to local rivers and streams—all while protecting residents from the growing threat of extreme storms and floods brought on by climate change.

Most municipalities, though, are ill-equipped to deal with the scope of the challenge. Derry Township had identified roughly $27 million in needed stormwater projects, but responsibility for maintaining the system was fractured across dozens of private homeowners' associations, businesses, and public entities.

In 2017, after months of engagement and feedback from the community, the township arrived at a solution. It transferred all the stormwater assets and responsibility for implementing a comprehensive township Stormwater Management Program to the Derry Township Municipal Authority, which had previously only handled the township's wastewater program. The Authority then established a special program to focus exclusively on a comprehensive stormwater management program and, importantly, instituted a dedicated stormwater fee to fund it.

The fee charges homeowners and businesses a rate based on the amount of pavement and other hard surfaces (also called impervious area) on their property. Because those surfaces contribute to the problem of stormwater runoff by stopping water from soaking into the ground, the fee ties the source of the problem directly to funds for its solution. The fee amounts to roughly $78 annually for a typical home, collectively providing $1.6 million per year for the stormwater program.

Callahan, who manages the program, says it allows the Authority to take a comprehensive look at chronic flooding and water quality issues across the landscape.

"What you find when you start digging in is, the problem here is related to the problem upstream, which is related to this other problem upstream," he says. "You're looking at the symptoms; the disease is the whole watershed. We've very much tried to piece together those problem areas and look holistically at the best way to solve them."

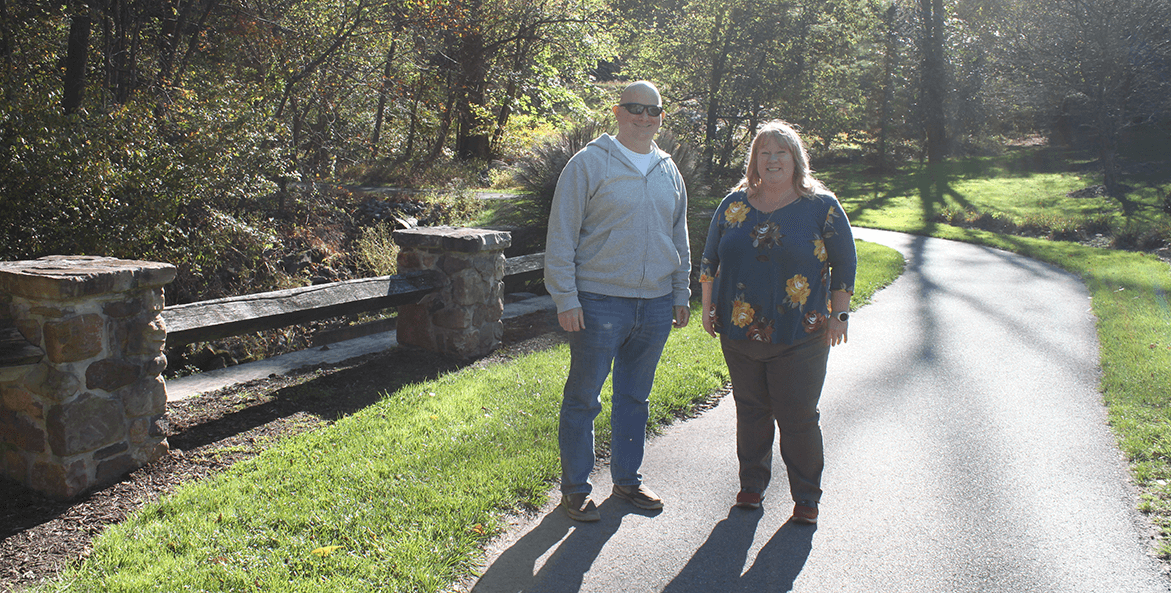

Mike Callahan (left) was hired to manage Derry Township's new stormwater program. The program uses a fee to pay for important upgrades to existing gray infrastructure. It has also worked with the Keystone 10 Million Trees Partnership, managed by CBF's Brenda Sieglitz (right), to implement green infrastructure projects like forested stream buffers that reduce pollution and flooding.

Codi Yeager/CBF Staff

It's a fundamental change from the way most cities historically approached stormwater. Early management systems often relied on funneling rain and floodwaters directly down roadways into nearby streams. Even after developments began requiring large retention basins, many filled with sediment and vegetation, reducing their ability to hold stormwater. And as towns grew, they often straightened and channelized streams, limiting the water's ability to expand over natural floodplains during storms.

The legacy is more severe floods and degraded water quality, both locally and downstream in the Bay.

"The big problem is you're sending a lot of water with a lot of velocity into stream channels that weren't receiving that kind of volume and velocity previously," says Callahan. "The sediment [pollution] is coming from the erosion of the streambanks."

Sediment in the stream harms fish and wildlife habitat, and erosion can cause property damage for nearby homes. The Authority is legally responsible for fixing the water quality problem through its stormwater (MS4) permit, which is issued by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection under the federal Clean Water Act.

Getting those streams off Pennsylvania's "impaired" stream list is just as important as addressing the flood problem, Callahan says.

"You can jump through the permit hoops and fulfill your requirements from a paperwork perspective, but never really solve your problems," he says. "We view it as we have impaired streams, so we need to fix those impaired streams."

That means tackling the root causes of poor water quality and localized flooding, whether it's through planting streamside tree buffers, replacing aging pipes, or reducing the amount of hard surfaces used in developments.

The Keystone 10 Million Trees Partnership, managed by CBF, partnered with the Derry Township Muncipal Authority to plant a protective buffer of trees along a stream badly eroded by stormwater runoff. The trees will help slow down the flow of water and pollution from the surrounding landscape.

Codi Yeager/CBF Staff

While there's still a lot of work to do, having a stormwater authority and fee system in place is allowing the Derry Township Municipal Authority to make real improvements.

In 2018, the Authority completed 30 projects using funding from the stormwater fee. The projects included emergency repairs to failing pipes that had created sinkholes, the installation of larger pipes to accommodate a growing community, and efforts to map and assess the condition of the township's stormwater infrastructure to pinpoint problem areas. It was also an early partner in the Keystone 10 Million Trees Partnership, which is coordinated by CBF, and has since completed several tree planting projects to help buffer streams and slow the rush of stormwater and pollution flowing from developed land.

"The biggest thing I heard from our public meetings is this is just another government money grab," Callahan says. "People thought, it's going to be money out of my pocket and nothing is going to change. Our program is very much focused on showing them we are doing something with it."

As Pennsylvania communities continue to develop and grow, addressing stormwater is key to stemming pollution locally and in the Bay, and helping with their own flooding problems. CBF is working with municipalities across the Commonwealth to find solutions, from planting trees to exploring how farmland can be leveraged to more cost-effectively address stormwater issues and stormwater permit requirements. You can learn more about our work here.