This op-ed was originally published in the Bay Journal.

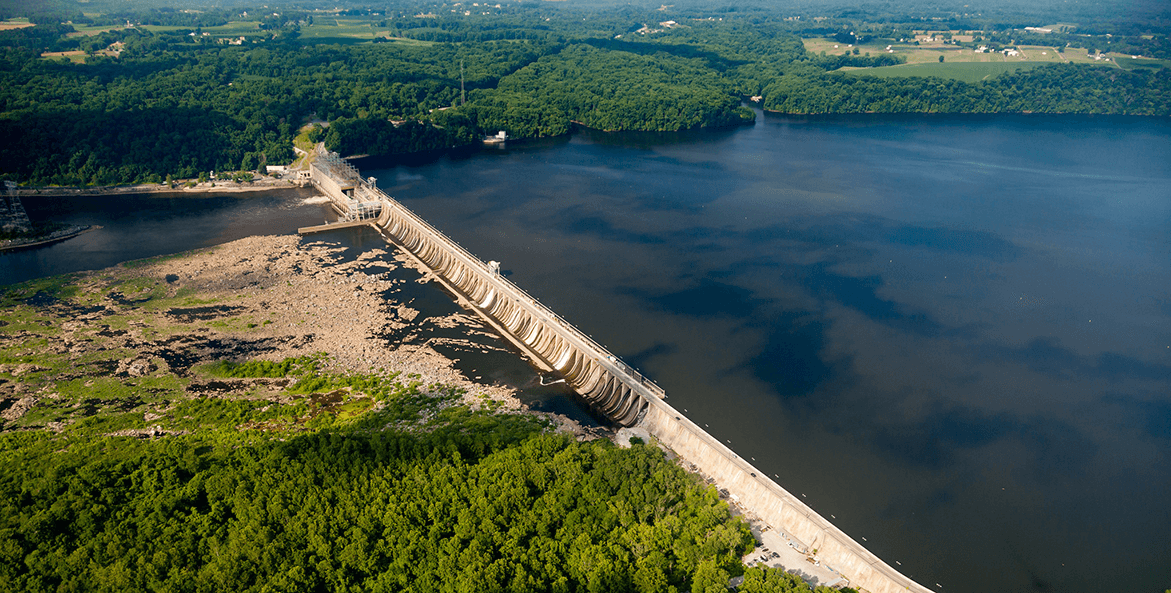

The Conowingo hydropower dam, the largest on the Susquehanna River, is poised to secure a federal license to operate for another 50 years.

Conowingo was built in 1928 to generate electricity for the regional power grid. Inadvertently, it long acted as a trap for nutrient and sediment pollution flowing down the Chesapeake Bay’s principal tributary. But over the years, sediment buildup in the dam’s reservoir significantly reduced its pollution-trapping capacity — so much so that the Chesapeake Bay Program estimates watershed states will need to cut an additional 6 million pounds of nitrogen and 260,000 pounds of phosphorus pollution to meet water quality goals in the Bay.

Exelon’s operation of the dam alters the form and timing of pollution to the Bay. During storms or other events that result in high flows, slugs of sediment laden with phosphorus are released downstream. The problem is only expected to worsen as the climate changes. The Bay Program’s latest modeling suggests that by 2050, increased rainfall and more intense storms will cause more pollution to flow out of Conowingo than flows into the dam. In other words, as the river scours legacy phosphorus and sediment from the dam’s reservoir, Conowingo will become a larger source of pollution than it is now.

In October, the state of Maryland announced it had reached a settlement agreement with Exelon, the dam’s operator, resolving an 18-month-long dispute over a water quality certification the company needs to renew its federal license. At issue were stipulations in the certification that would have required Exelon to significantly curb pollution flowing through the dam. The settlement instead allows Exelon to invest $200 million in projects, only a portion of which are aimed at improving water quality and aquatic life in the Susquehanna River and downstream in the Bay.

The agreement has significant shortcomings. It provides just a fraction of the funding Exelon could afford while still netting a profit from the dam, and many of the water improvement projects it identifies, while laudable, do little to stem nitrogen and phosphorus pollution.

But most troubling is the missed opportunity to meaningfully address the root of the problem: upstream pollution in Pennsylvania. In 2016, an assessment by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Maryland Department of Environment identified the need to address pollution flowing into the dam’s reservoir, but only a small portion of the funds outlined in the settlement would target practices that directly reduce sediments and nutrients from upstream areas.

Failing to stem the tide of soil, fertilizer and manure washing into the Susquehanna from Pennsylvania’s agricultural heartland not only exacerbates the Conowingo problem; it puts restoration efforts across the Bay watershed at risk.

The reason is threefold. First, the Susquehanna River is the Bay’s largest source of freshwater and is responsible for half of its nitrogen pollution.

Second, Pennsylvania, which covers the bulk of the river’s watershed, is responsible for more than two-thirds of the nitrogen reduction required to meet restoration goals outlined in the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint.

And third, agriculture accounts for 80% of the pollution reductions Pennsylvania needs to make.

Bottom line, we can’t restore the Chesapeake Bay, or the watershed’s rivers and streams, without addressing agricultural pollution in Pennsylvania that flows into the Susquehanna.

Many farmers in Pennsylvania are eager to implement practices on their land that reduce pollution, but they need financial and technical support to put them in the ground.

Each of the six Bay states and the District of Columbia are responsible for outlining how they will reach the pollution reduction goals outlined in the Clean Water Blueprint. But to date, Pennsylvania has not provided a plan that meets its goals, and the state’s lawmakers have not provided the investment needed to achieve them.

In the absence of leadership and commitment from Pennsylvania legislators, the success of the Blueprint depends on the federal government holding Pennsylvania accountable to its commitments. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, as the lead federal agency, has a unique oversight role in the partnership restoring the Bay. EPA has the ability to impose financial and regulatory consequences if Pennsylvania does not muster the political will to help its farmers cut pollution, and the agency must do so.

With just five years to go until the Blueprint’s 2025 deadline, continued inaction will only make the challenge steeper and more costly. The growing threat posed by the Conowingo dam and the inadequacy of the settlement agreement are a reminder of what’s at stake if we don’t tackle upstream pollution now.

Lisa Feldt, CBF Vice President for Environmental Protection and Restoration

Issues in this Post

Runoff Pollution

Conowingo Dam and

Chesapeake Bay Runoff Pollution Water Quality