As an educational tool, marsh mud is hard to beat. It’s the perfect place to lay down, listen, and absorb all the sights, smells, and sounds of the Bay. And pretend to be a muskrat.

Fox Island had a lot of marsh mud in the 1980s. I first saw it in the fall of 1981, when I worked as an environmental educator for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. We would take teachers and students out marsh mucking, and there was a great grass bed where we could run a grass net to pull up a rich abundance of wildlife. It was experiential, hands-on, sensory stuff.

Three people paddle in a canoe in the waters surrounding Fox Island.

Cindy Dunn

Fox was transformative for the kids and their teachers. From the moment they saw the building emerge as a spot on the water from the boat, the island got them out of their routine and the normal context of their lives in a way few places can. They walked on the beach and set crab traps and found great merriment in the propane-fire toilets we used at the time. It was stark, and they loved it. They understood the Bay as a living thing.

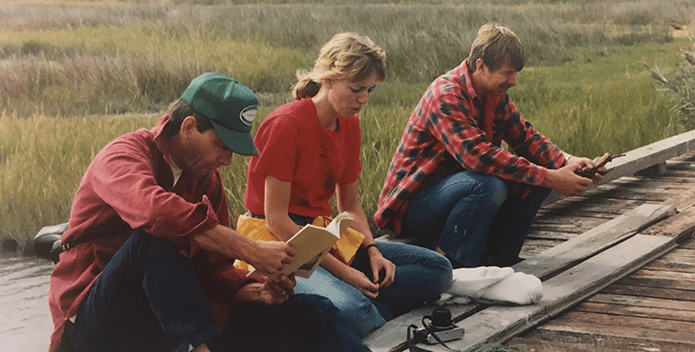

I went back to Fox with some friends from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources last year. It is still transformative. It still has an unmatched ability to inspire and connect people with nature. But it is greatly changed.

The marshes surrounding the education center are just a sliver of what they used to be. Sea level rise and erosion, due to global climate change and a regional sinking of the land known as subsidence, have reduced the land area of Fox Island by more than 70 percent in the last 50 years.

Climate change often feels abstract, but this is happening right here at home. And it’s not just Fox.

Cindy Dunn, the current Pennsylvania Secretary of Conservation and Natural Resources, stands on a dock surrounded by sail boats.

Cindy Dunn

We see the effects of climate change across the Bay watershed. Beyond the rising sea levels that pose an imminent threat to coastal wetlands and communities, air and water temperatures are getting warmer. That’s a big challenge for cold water fisheries in Pennsylvania and the diversity of our forests, which are essential for clean water.

Making streams more resilient to warming temperatures, through actions such as planting streamside trees, is important to help our state and our watershed mitigate and adapt to climate change. That’s why DCNR has made planting streamside buffers a priority practice and is working with the Keystone 10 Million Trees Partnership to transform the landscape of Pennsylvania and clean its rivers and streams.

An equally critical part of the solution is educating the next generation of environmental stewards. Education creates the foundation for a conservation ethic. It instills environmental values in our communities and gives us the tools to build resilience.

Nothing makes the connection stick quite like getting students and teachers into the field in great outdoor spaces. Sadly, we are losing one of the best at Fox. But for all the students, teachers, and visitors who mucked its marshes, the connection to the Bay—and the outdoors—will far outlast the island.

Cindy Adams Dunn, Pennsylvania Secretary of Conservation and Natural Resources