When he called on the phone, I could literally hear my friend John Flood smile through the wire as he chuckled, "I haven't lost my touch, and I'm going to have a GREAT lunch." He had been working on a living shoreline restoration project at the Severn River home of a mutual friend when he noticed a crab slough (empty shell) lying in a bed of underwater redhead grass. Lifelong river rat that he is, his mental reflex was to reach into the grass beside the slough, where his hand fell immediately on the six-inch "Whale" soft crab that had just extricated itself from the shell. Even better, twenty feet away, he saw another slough and this time extracted an even larger Whale. Good thing. Shoreline work gives him a big appetite.

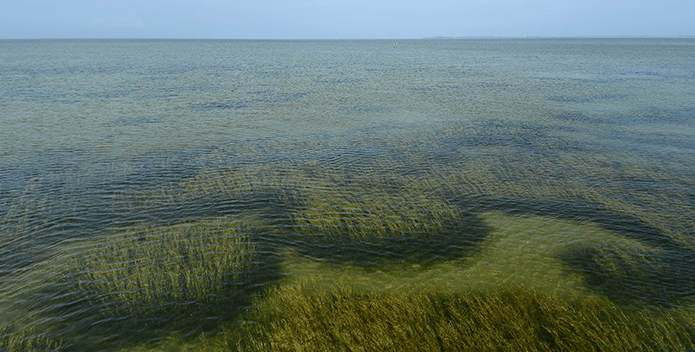

Like me, John counts the decades of his life on more than one hand, but the truth is that for some years, his native South River has not given him many opportunities to exercise that touch, because its grasses died out, victims of pollution from nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment. The good news, though, has been steady increases of underwater Bay grass beds (also known as Submerged Aquatic Vegetation or SAV) over the past six years, according to the annual Bay-wide survey conducted for the Chesapeake Bay Program Partnership by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, and multiple partners, including several groups of citizen volunteers. The health of these Chesapeake underwater prairies is a critical index to the health of the Bay ecosystem as a whole. Thick grass beds composed of multiple species are "keystone ecological communities" that provide food and habitat for some of our best-loved Bay critters, including crabs, fish, and migratory waterfowl.

Two years ago, the 2017 survey found more than 100,000 acres (officially 104,893 acres) for the first time since the Bay Program survey began in 1984 (where it sat at just over 38,000 acres). That survey far exceeded the program's 2017 goal of 90,000 acres. It was great news. The obvious conclusion is that the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working. Bay scientists cite recent ecosystem studies that clearly support that conclusion.

After last year's record-breaking rainfall across the entire Chesapeake watershed, though, with the runoff pollution that it carried into the Bay’s streams and rivers, the big worry has been that the 2018 grasses survey numbers would drop. Instead, the Bay Program’s newest survey shows our grasses held their own last year, a clear sign that the ecosystem is developing more resilience to absorb shocks driven by unusual weather. It’s great news, buoyed even further by many anecdotal reports like John Flood’s of thick grass beds this year, in parts of the Severn that have been bare for many years, as well as in his beloved South River, on the Susquehanna Flats, in the Honga River, and down the Bay in places like Mobjack Bay. The Clean Water Blueprint is clearly working. We are on the right track.

That said, there are still parts of the Chesapeake lacking grass beds that were there historically. The Bay program’s goal is 130,000 acres by 2030 and 185,000 acres by 2050 (an approximation of what grew here in the early nineteenth century). The glass is clearly more than half-full, and we celebrate the progress daily with stories like John Flood’s excellent lunch, but we also clearly have more work to do. Let’s finish the job!