It's a double irony that we need an Endangered Species Day to remember fish like the Maryland darter, indigenous to three Susquehanna River tributaries in Harford County, Maryland, which has disappeared apparently due to careless human development in those watersheds. Invariably, the damage sustained by those streams is the kind that the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is designed to correct. Thus appropriate commemoration of Endangered Species Day includes a re-dedication to the Bay states' renewal of their Watershed Implementation Plans (WIPs) (in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania), the specifics of the Blueprint designed to take us to its goals for 2025.

The second stage of the irony, though, is that even as we mourn that lovely but regionally restricted little fish, we forget to consider the plights of several others that have played important roles throughout the Chesapeake ecosystem. Here are four more that are laboring under serious threats to which the Clean Water Blueprint and its renewed WIPs speak:

- River herring—These are the alewives and blueback herring that have for millennia in April and May entered from the Atlantic and ascended the Chesapeake's rivers into fresh water to spawn. The adults leave afterward, but the newly-hatched young remain and grow for the summer before following their parents to form vast schools in the ocean. Along the way, they form a significant element in the forage base for predators that range from humans, river otters, and ospreys to whales, striped bass, and gannets. Unfortunately, overfishing in the 19th century began the decline; dams on the rivers in the 20th century closed off hundreds of miles of spawning habitat; and declining water quality has damaged what is left. The final insult has been heavy bycatch by factory trawlers in the Atlantic targeting Atlantic herring, with which the river herring mix at sea. The result is that herring fishing is closed in most of the rivers along the Atlantic coast, including all of ours. Our Bay needs them back!

- American eels and freshwater mussels—We’ll take these two together because of an amazing link in their complex life cycles. American eels literally reverse the live cycle of the river herring. They live in fresh water but spawn in the Atlantic’s Sargasso Sea. They live for 5-20 years, with females ascending dozens and even hundreds of miles upstream, to live in streams, ponds, and lakes till they mature and return to the Sargasso, where they spawn and die. Remarkably, they function as hosts for several species of freshwater mussels, especially the eastern elliptio. On rivers like the Susquehanna, high dams have blocked the migrations, creating a double whammy for both the eels and their mussel passengers, which historically played major clean-water roles in those waterways. Meanwhile, heavy fishing pressure in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s greatly reduced the Chesapeake’s eel stocks.

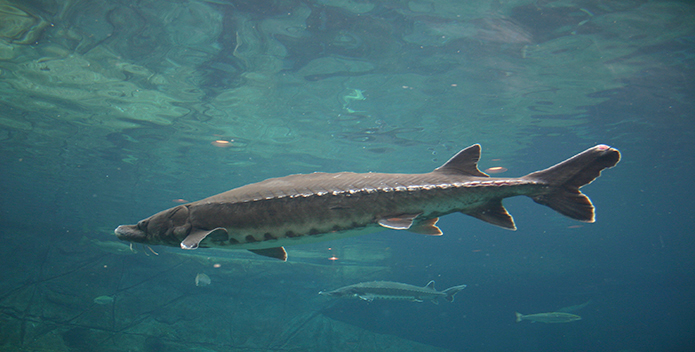

- Atlantic sturgeon—Once thought extinct in the Chesapeake, these huge, mysterious fish appear to be making a slow and fragile but encouraging comeback, especially in the James River, the Pamunkey (a tributary of the York), and Marshyhope Creek (the northwest branch of the Nanticoke). They too spawn in fresh water but wander the Atlantic’s continental shelf, living as long as sixty years and growing to lengths of fourteen feet (really!). They are officially federally endangered in all the Atlantic’s river systems except those of the Gulf of Maine, where they are considered threatened. Their problems are predictable: overfishing for caviar and meat in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (all too easy with slow-growing species that take 15-20 years to mature) and habitat degradation, especially the benthic (bottom) communities where they feed. Even so, their apparently renewed presence in the James, where they may be seen breaching during their September spawning run, is encouraging.