At first glance, the handful of grass and twigs netted from the shore of the Severn River revealed little. Until it jumped.

"Grass shrimp!" said John Page Williams, CBF’s senior naturalist. He pointed to a tiny, translucent critter no bigger than a fingernail. Suddenly, like an optical illusion coming into focus, I could see half a dozen shrimp materialize between the bits of detritus. It was impossible not to bend for a closer look.

Tiny grass shrimp live in underwater grass beds in the Chesapeake Bay and are an important part of the food chain.

Codi Kozacek

I was awed. The shrimp, impatient to return to their breakfast of decomposing vegetation, were less amused. As if to say, that’s quite enough, thank you, they contracted their bodies and sprang from the net, popping into the shallow water.

Thus rebuffed, but not disheartened, my introduction to the Chesapeake Bay began.

I hail from the shores of another iconic body of water—the Great Lakes—but before this month I knew the Chesapeake only by reputation. And it’s some reputation. The years I spent writing about toxic algal blooms in Lake Erie were peppered with references to the gold standard of large-scale environmental restoration: the collaborative, multi-state effort to save the Bay. The question was always, how can we replicate that here?

The Chesapeake, therefore, grew to mythical proportions in my mind. I whooped when I passed the sign marking the watershed’s western reaches, on the highway in Pennsylvania. Later, I wasted no time driving across the winding arc of the Bay Bridge to spend a blissful Saturday spotting frogs, turtles, and osprey at Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. But as I’ve been told, you can’t know the Bay until you’ve been on the Bay.

So, it was with a thrill that I stepped onto John Page’s skiff, First Light, and we pushed away from the dock into the Severn.

It felt as if I was meeting a very famous person, only to discover they were delightfully down-to-Earth. The water was languid, meandering in and out of hidden fingers and coves. In many places, homes perched above the shore to take in the views. In others, forested hillsides tumbled down steep sandy banks to the water’s edge.

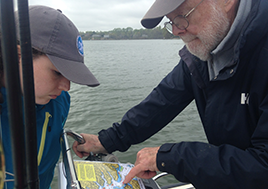

CBF staff members John Page Williams (right) and Brittany Wright study a chart of historic oyster bars on the Severn River, Maryland.

Codi Kozacek

It’s a waterscape that invites imagination—both of what has been and what will be. How can you resist, on a river like the Severn, squinting into the past to conjure the vast oyster reefs that once crenelated its bars and bends? How can you look at the boat slips and riverside homes and not see the decades of fishing trips and tranquil summer days unfolding along its shores? And how can you not be enchanted by a vision of the summer days to come, even more vibrant because we return the Bay to robust health?

If restoring the Bay was an easy task, it would be done already, John Page remarked. But what struck me most, as we pulled out of a small inlet and headed into the river’s main channel, is that it can be done and it is being done.

Case in point: We had just finished examining two pocket wetlands, mirror images on either side of the cove.

One sat at the mouth of a ravine that drained an area developed before the enactment of the Critical Area Protection Program in 1984. The Maryland legislation aimed to institute better development practices to safeguard the Bay’s water quality and habitats. The wetland was largely taken over by invasive Phragmites, a reed grass that thrives in disturbed areas—such as those created when rainfall hits pavement and rushes quickly downstream, scouring out the mud that shelters native grass seeds.

CBF Senior Naturalist John Page Williams shows off some young Bay grasses from the Severn River. Underwater grass beds provide crucial habitat for crabs and fish, as well as food for water fowl.

Codi Kozacek

On the other side of the cove, however, was a pocket wetland fed by a stream that flowed from hillsides developed later, after more stringent and important protections were put in place. As a result, the water moved more slowly down to the Bay, allowing native grasses and other plants to grow atop a thick layer of muck.

It was a clear illustration that our actions have tangible consequences for the Bay, and we can shape it for the better. Moreover, we have a plan to do so: the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint. The Blueprint, for the first time, sets enforceable pollution reduction targets by 2025 and lays out the steps to meet them for each of the six Bay States and the District of Columbia.

Key indicators show that it is working. In 2017, underwater grasses, a key habitat for crabs and fish, covered the largest area on record. Even after heavy rainfall sent more pollution into the Bay last year, there are signs the grasses have been resilient.

As we headed back toward the dock, John Page pointed at the depth sounder on the skiff’s console. The flat gray lines began to waver and lift into filamentous gray fuzz on the screen. "Those are the grasses," he said. We stepped to the side of the skiff and peered over the edge. At first, we saw nothing. Then, we spotted them: spectral tendrils streaming just under the surface of the water, striving for the new spring light.