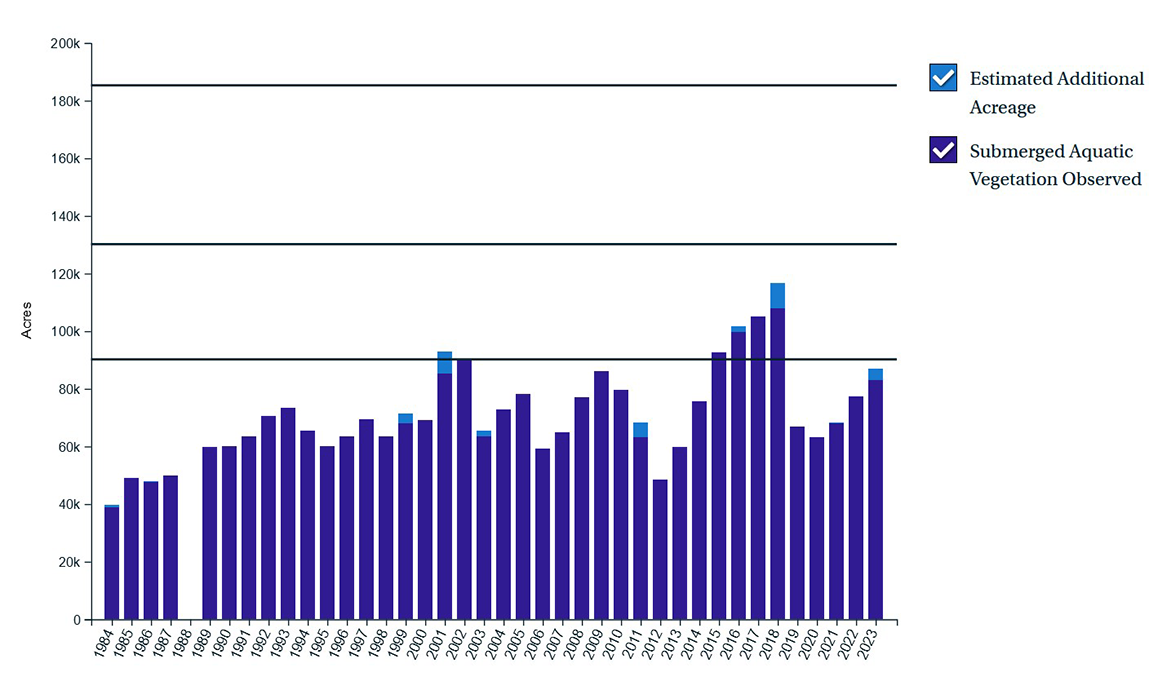

At its most pristine, the Bay may have supported several hundred thousand acres of underwater grasses. Since the 1950s, there has been a tremendous decline of grass beds due to degraded water quality and climate change. CBF is working to help meet the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement target of 185,000 acres of underwater grasses covering the bottom of the Bay and its tidal tributaries by 2025.

Importance of Underwater Grasses

- Underwater grasses filter polluted runoff, provide food for waterfowl, and provide essential habitat for blue crabs, juvenile rockfish (striped bass), and other aquatic species.

- Underwater grasses are one of the best barometers of the Bay's water quality because they are associated with clear water, and their presence helps improve water quality. Their leaves and stems baffle wave energy and help settle out sediments. Their roots and rhizomes bind the substrate.

- Underwater grasses also take up nitrogen and phosphorus that, in overabundance, lead to algae blooms that can degrade water quality. Decomposing underwater grasses provide food for benthic (bottom-dwelling) aquatic life.

- Migrating waterfowl, such as ducks and geese, rely on underwater grasses for food.

Threats

Like most grasses on land, underwater grasses require sunlight to grow and thrive. When the Bay's waters become clouded with sediment from stormwater runoff and algal blooms resulting from excess nutrients in the water, grasses find it harder to survive.

Restoration Status: Mixed

- 1972—Huge amounts of rainfall and runoff caused by Tropical Storm Agnes dealt a devasting blow to many grass beds. Underwater grasses continued to decline to a documented low of 38,000 acres in 1984.

- 1984 to 1993—Underwater grasses increased to 73,000 acres.

- Early 2000s—Underwater grasses were on the rise due to prolonged drought, which kept pollutants from the land locked in the soil. In 2001-2002, grasses increased to 90,000 acres in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

- Mid 2000s—Data collected in 2008 showed Bay grasses covering 73,063 acres, or 39.5 percent of the 2010 185,000-acre Bay restoration goal. The 2008 data show an 18 percent increase in underwater grasses from 2007.

- 2010 to 2012—Extreme heat in 2010 led to a significant decline in grasses in the lower Bay in 2011 and coverage dropped to an estimated 63,074 acres. High spring rains, Hurricane Irene, and Tropical Storm Lee all created poor conditions for growth in 2012 and coverage dropped again to an extimated 48,191 acres.

- 2013 to 2017—Acres of underwater grasses increased each year from 2013 to 2018. In 2017, there were more than 100,000 acres of underwater grasses in the Chesapeake Bay—the highest ever reported since monitoring began in the mid 1980s. Improvements in water clarity were also observed during this time. Researchers estimate they also surpassed 100,000 acres in 2018, though the survey was incomplete due to weather challenges. In 2018, frequent rain, cloudy water, and security restrictions prevented researchers from collecting data from more than 22 percent of the Bay and its tributaries. As a result, the 2018 Chesapeake Bay Program survey reported that it's likely that the actual expanse of underwater grasses ranged between 91,559 and 108,960 acres.

- 2019—Acreage declined by 38 percent. According to the annual Chesapeake Bay Program survey the precise reason for the decline is unknown. However grasses did undergo a massive assault from record-breaking river flows, which wash more pollution into the Bay. In fact, the 2019 Water Year (October 1, 2018 through September 30, 2019 recorded the largest average annual flow of fresh water into the Bay since records began in 1937.

- 2020—Acreage declined again, but this time by just 7 percent. According to the 2020 Chesapeake Bay Program survey, grass acreage rebounded in fresh water and low salinity areas at the top of the Bay and in high-salinity areas close to the mouth. Grass beds in the mid-region, however, took a hit. These areas are mostly populated with widgeon grass, a species that is known for disappearing when conditions are bad but bouncing back a few years later.

- 2021—Acreage increased 9 percent, but is still an approximate 38 percent decline from the high in 2018, according to the 2021 Chesapeake Bay Program survey. The small gain was largely attributed to an increase in widgeon grass, which fluctuates with weather and water quality, so is not a reliable indicator of the long-term health of Bay grasses.

- 2022—Acreage increased another 12 percent, to approximately 76,400 acres, according to the 2022 Chesapeake Bay Program survey. The Chesapeake is grouped into four different salinity zones, reflecting the different types of grasses that thrive in each region. Underwater grass beds in the tidal fresh and slightly salty zones decreased, while areas that are moderately and very salty saw significant increases in grass beds.

- 2023—Acreage increased another 7 percent, to approximately 82,937 acres, according to the 2023 Chesapeake Bay Program survey. Slightly salty areas of the Bay saw a major decrease attributed to algal blooms and sediment, while cooler water stemming from La Niña fueled a significant increase in the saltier Lower Bay’s underwater grasses. According the the survey press release, "These are positive gains, but they do not offset the decline of underwater grasses that occurred in 2019, making it unlikely that the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement outcome will be met by 2025."

- 2030-2050—The Bay Program's goal is 130,000 acres by 2030 and 185,000 acres by 2050 (an approximation of what grew here in the early nineteenth century).

From a low of less than 40,000 acres in 1984, underwater grasses peaked in 2018.

ChesapeakeStat

Solutions

In Bay restoration we don't often see straight-line progress, and declines in underwater grasses in the Bay are a sobering reminder that extreme weather can set back recovery. It also reminds us that we need to focus on the elements we can control, especially reducing pollution to the Bay and its rivers and streams.

Though we can't control Mother Nature, reducing pollution—including better managing stormwater runoff before it gets into rivers and streams—will help mitigate weather extremes, improve water quality, and contribute to Bay grass revival. The 2018 survey seems to support that theory. Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, the other Bay states, and the District of Columbia all committed to reducing pollution from all sources as their part of their Clean Water Blueprint. In a July 2024 press release, CBF Vice President for Environmental Protection and Restoration Alison Prost commented, "For a healthier future Chesapeake Bay, Bay watershed leaders must recommit to the Bay partnership this December (2024) and chart a future course for Bay restoration that addresses new challenges like climate change and reflects scientific updates. Those scientific recommendations include focusing restoration efforts on shallow-water habitat. If that is done, we could reach the 185,000-acre goal.”

All of CBF's activities—from land-use planning and stormwater management to wetland protection and riparian buffer planting—contribute to Bay grass revival.

Progress is being made, but many local waterways and the Chesapeake are still polluted. If we don't keep making progress, we will see more signs declining grasses numbers, and we will continue to have polluted water, human health hazards, and lost jobs—at a huge cost to society.